Spanish language: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [accepted revision] |

No edit summary |

Undid revision 1267810890 by Pniacakddoes (talk) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Romance language}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Español}} |

|||

{{pp-pc|small=yes}} |

|||

{{redirect|Castellano|the surname|Castellano (surname)}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox Language |

|||

{{Use American English|date=February 2023}} |

|||

|name = Spanish, Castilian |

|||

{{Redirect|Castilian language|the specific variety of the language|Castilian Spanish|the broader branch of Ibero-Romance|West Iberian languages}} |

|||

|nativename = {{lang|es|Español}}, {{lang|es|Castellano}} |

|||

{{Infobox language |

|||

|pronunciation =/espaˈɲol/, /kasteˈʎano/ or /kasteˈʝano/ |

|||

| |

| name = Spanish |

||

| altname = Castilian |

|||

|script = [[Latin alphabet|Latin]] ([[Spanish alphabet|Spanish variant]]) |

|||

| image = |

|||

|region = '''[[Hispanophone world|Spanish speaking countries]]:'''<br/>[[Argentina]], [[Belize]], [[Bolivia]], [[Chile]], [[Colombia]], [[Costa Rica]], [[Cuba]], [[Dominican Republic]], [[Ecuador]], [[Equatorial Guinea]], [[El Salvador]], [[Guatemala]], [[Honduras]], [[Mexico]], [[Nicaragua]], [[Panama]], [[Paraguay]], [[Peru]], [[Puerto Rico]], [[Spain]], [[Uruguay]], [[Venezuela]], and a significant numbers of the populations of [[Andorra]], [[Gibraltar]], and the [[United States]]. |

|||

| nativename = {{hlist|{{lang|es|español}}|{{lang|es|castellano}}}} |

|||

|speakers = First language<sup>a</sup>: 322<ref>[http://encarta.msn.com/media_701500404/Languages_Spoken_by_More_Than_10_Million_People.html Encarta-Most Spoken languages]</ref>– c. 400 million<ref>[http://www.ciberamerica.org/Ciberamerica/Castellano/General/Noticias/detalle?id=8832 Ciberamerica-Castellano]</ref><ref>[http://archivo.elnuevodiario.com.ni/2004/febrero/15-febrero-2004/especiales/especiales2.html El Nuevo Diario]</ref><ref>[http://www.terra.com/noticias/articulo/html/act821930.htm Terra Noticias]</ref> <br/>Total<sup>a</sup>: 400–500 million<ref name = "universidad de mexico">[http://209.85.135.104/search?q=cache:v5IUdEETu40J:www.lllf.uam.es/~fmarcos/coloquio/Ponencias/MMelgar.doc+%22En+el+mundo+lo+hablan+aproximadamente+400+millones+de+personas%22+%22Adicionalmente+100+millones+de+personas+hablan+espa%C3%B1ol+como+segunda+lengua%22&hl=es&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=es Universidad de México]{{Verify credibility|date=March 2008}}{{subst:Sup|(cached URL)}}</ref><ref name="instituto cervantes">Instituto Cervantes ([http://66.102.9.104/search?q=cache:0i7Y43lUanEJ:www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2007/04/26/cultura/1177610767.html+%22Instituto+Cervantes%22%22los+actuales+500+millones+de+hispanohablantes+en+Latinoam%C3%A9rica+y+Espa%C3%B1a%22&hl=es&ct=clnk&cd=2&gl=es "El Mundo" news])</ref><ref>[http://yhoo.client.shareholder.com/press/ReleaseDetail.cfm?ReleaseID=173481 Yahoo Press Room]</ref> <br><sup>a</sup><small>All numbers are approximate.</small> |

|||

| pronunciation = {{IPA|es|espaˈɲol||Es-español.oga|}}<br/>{{IPA|es|kasteˈʝano||Es-Castellano.oga}}, {{IPA|es|kasteˈʎano||Es castellano 001.ogg}} |

|||

|rank = 2 (native speakers)<ref name="ethnologue">{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=spa|title=Spanish|publisher=ethnologue}}</ref><ref>[http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/most_spoken_languages.htm Most widely spoken languages by Nations Online]</ref><ref>[http://www.askmen.com/toys/top_10/45b_top_10_list.html Most spoken languages by Ask Men]</ref><ref>[http://encarta.msn.com/media_701500404/Languages_Spoken_by_More_Than_10_Million_People.html Encarta Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People]</ref><br>3 (total speakers) |

|||

| speakers = Native: 500 million |

|||

|fam2 = [[Italic languages|Italic]] |

|||

| |

| date = 2023 |

||

| |

| ref = <ref name="viva18" /> |

||

| speakers2 = Total: 600 million<ref name="viva18" />{{br}}100 million speakers with limited capacity (23 million students)<ref name="viva18" /> |

|||

|fam5 = [[Gallo-Iberian]] |

|||

| speakers_label = Speakers |

|||

|fam6 = [[Ibero-Romance languages|Ibero-Romance]] |

|||

| familycolor = Indo-European |

|||

|fam7 = [[West Iberian languages|West Iberian]] |

|||

| |

| fam2 = [[Italic languages|Italic]] |

||

| |

| fam3 = [[Latino-Faliscan languages|Latino-Faliscan]] |

||

| fam4 = [[Latin]] |

|||

|nation = [[List of countries where Spanish is an official language|21 countries]] |

|||

| fam5 = [[Romance languages|Romance]] |

|||

|agency = [[Association of Spanish Language Academies|{{lang|es|Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española}}]] ({{lang|es|[[Real Academia Española]]}} and 21 other national Spanish language academies) |

|||

| |

| fam6 = [[Italo-Western languages|Italo-Western]] |

||

| |

| fam7 = [[Western Romance languages|Western Romance]] |

||

| |

| fam8 = [[Iberian Romance languages|Ibero-Romance]] |

||

| fam9 = [[West Iberian languages|West Iberian]] |

|||

| fam10 = [[Castilian languages|Castilian]]<ref>{{Harvcoltxt|Eberhard|Simons|Fennig|2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|chapter=Castilic|chapter-url=http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/cast1243|editor1-first=Harald|editor1-last=Hammarström|editor2-first=Robert|editor2-last=Forkel|editor3-first=Martin|editor3-last=Haspelmath|editor4-first=Sebastian|editor4-last=Bank|year=2022|title=[[Glottolog|Glottolog 4.6]]|edition=|location=Jena, Germany|publisher=Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology|ref={{sfnref|Glottolog|2022}}|access-date=19 June 2022|archive-date=28 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220528095200/https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/cast1243|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| ancestor = [[Vulgar Latin]] |

|||

| ancestor2 = [[Old Spanish]] |

|||

| ancestor3 = [[Early Modern Spanish]] |

|||

| script = [[Latin script]] ([[Spanish alphabet]])<br />[[Spanish Braille]] |

|||

| nation = {{Collapsible list | titlestyle = font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left; | title = [[List of countries where Spanish is an official language|20 |

|||

countries]]| |

|||

|[[Argentina]] |

|||

|[[Bolivia]] |

|||

|[[Chile]] |

|||

|[[Colombia]] |

|||

|[[Costa Rica]] |

|||

|[[Cuba]] |

|||

|[[Dominican Republic]] |

|||

|[[Ecuador]] |

|||

|[[El Salvador]] |

|||

|[[Equatorial Guinea]] |

|||

|[[Guatemala]] |

|||

|[[Honduras]] |

|||

|[[Mexico]] |

|||

|[[Nicaragua]] |

|||

|[[Panama]] |

|||

|[[Paraguay]] |

|||

|[[Peru]] |

|||

|[[Spain]] |

|||

|[[Uruguay]] |

|||

|[[Venezuela]]}} |

|||

<br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=[[List of countries where Spanish is an official language|Dependent territories]]| |

|||

|[[Puerto Rico]]}} |

|||

<!-- This list is intended for subnational territories that do not form an integral part of a country (such as Puerto Rico), as well as integral parts of nations that are not traditionally considered Spanish-speaking. Adding Ceuta and Melilla will result in deletion as they are integral parts of Spain. This also applies to Chile and the case of Easter Island. --> |

|||

<br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=[[List of countries where Spanish is an official language|Partially recognized country]]| |

|||

|[[Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic]]}} |

|||

<!-- This list is intended for countries with limited recognition where Spanish is an official language. --> |

|||

<br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=[[List of countries where Spanish is an official language|Significant minority]]| |

|||

|[[Andorra]] |

|||

|[[Belize]] |

|||

|[[Gibraltar]] |

|||

|[[United States]]}} |

|||

<!-- This list is only intended for countries and territories where Spanish is currently spoken by a significant minority of the population (~20% or more) and is used as a major working language in government and other institutions. The Philippines, Morocco, Western Sahara, Guam, the Mariana Islands, and other former historic Spanish colonies where considerably less than 20% of the population speaks standard Spanish should not be listed here. --> |

|||

<br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;| title = [[List of countries where Spanish is an official language#International organizations|International<br />organizations]]| |

|||

|[[African Union]] |

|||

|[[Andean Community]] |

|||

|[[Association of Caribbean States]] |

|||

|[[Caribbean Community]] |

|||

|[[Community of Latin American and Caribbean States|CELAC]] |

|||

|[[European Union]] |

|||

|[[Latin American Integration Association|ALADI]] |

|||

|[[Latin American Parliament]] |

|||

|[[Mercosur]] |

|||

|[[Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe|OSCE]] |

|||

|[[Organization of American States]] |

|||

|[[United Nations]] |

|||

|[[Union of South American Nations]] |

|||

|[[Organization of Ibero-American States]]}} |

|||

| agency = [[Association of Spanish Language Academies]]<br />({{lang|es|[[Real Academia Española]]}} and 22 other national Spanish language academies) |

|||

| iso1 = es |

|||

| iso2 = spa |

|||

| iso3 = spa |

|||

| lingua = 51-AAA-b |

|||

| sign = [[Signed Spanish]] (using signs of the local language) |

|||

| glotto = stan1288 |

|||

| glottorefname = Spanish |

|||

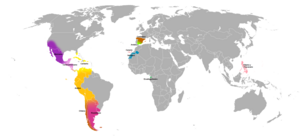

| map = File:Map-Hispanophone World.svg |

|||

| mapcaption = {{legend|#045a8d|Official majority language}} |

|||

{{legend|#0674b6|Co-official or administrative language but not majority native language}} |

|||

{{legend|#9bbae1|Secondary language (more than 20% Spanish speakers) or culturally important}} |

|||

| notice = IPA |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Spanish''' ({{lang|es|español}}) or '''Castilian '''({{lang|es|castellano}}) is a [[Romance languages|Romance language]] of the [[Indo-European language family]] that evolved from the [[Vulgar Latin]] spoken on the [[Iberian peninsula|Iberian Peninsula]] of [[Europe]]. Today, it is a [[world language|global language]] with about 500 million native speakers, mainly in the [[Americas]] and [[Spain]], and about 600 million speakers including second language speakers.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/spa/ |title=Ethnologue, 2022 |access-date=2 December 2023 |archive-date=7 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230507025019/https://www.ethnologue.com/language/spa/ |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="size" /> Spanish is the official language of [[List of countries where Spanish is an official language|20 countries]], as well as one of the [[Official languages of the United Nations|six official languages]] of the [[United Nations]].<ref name="un1">{{cite web | last=| first=| title=Official Languages | publisher=United Nations | url=https://www.un.org/en/our-work/official-languages | access-date=2024-01-05| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240105190533/https://www.un.org/en/our-work/official-languages| archive-date=2024-01-05}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |title=In which countries of the world is this language spoken? |url=http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/countries_by_languages.htm |url-status=live |access-date=23 January 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230629022556/https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/countries_by_languages.htm |archive-date=29 June 2023}}</ref> Spanish is the world's [[list of languages by number of native speakers|second-most spoken native language]] after [[Mandarin Chinese]];<ref name="size">{{cite web |last1=Eberhard |first1=David M. |last2=Simons |first2=Gary F. |last3=Fennig |first3=Charles D. |date=2022 |title=Summary by language size |url=https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/ethnologue200/ |work=Ethnologue |publisher=SIL International |language=en-US |access-date=2 December 2023 |archive-date=18 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230618002011/https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/ethnologue200/ |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Salvador |first=Yolanda Mancebo |title=Calderón en Europa |chapter-url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.31819/9783964565013-007/html |chapter=Hacia una historia de la puesta en escena de La vida es sueño |publisher=Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft |year=2002 |pages=91–100 |isbn=978-3-96456-501-3 |language=es |doi=10.31819/9783964565013-007 |access-date=3 March 2022 |archive-date=3 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220303220424/https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.31819/9783964565013-007/html |url-status=live}}</ref> the world's [[list of languages by total number of speakers|fourth-most spoken language]] overall after [[English language|English]], Mandarin Chinese, and [[Hindustani language|Hindustani]] ([[Hindi]]-[[Urdu]]); and the world's most widely spoken Romance language. The country with the largest population of native speakers is [[Mexico]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Countries with most Spanish speakers 2021 |url=https://www.statista.com/statistics/991020/number-native-spanish-speakers-country-worldwide/ |website=[[Statista]] |access-date=17 May 2022 |archive-date=17 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220517000420/https://www.statista.com/statistics/991020/number-native-spanish-speakers-country-worldwide/ |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

'''Spanish''' ({{Audio|español.ogg|''español''}}) or '''Castilian''' (''castellano'') is a [[Romance languages|Romance language]] that originated in northern [[Spain]], and gradually spread in the Kingdom of [[Kingdom of Castile|Castile]] and evolved into the principal language of government and trade. It was taken to [[Spanish Empire#Territories in Africa (1898–1975)|Africa]], the [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Americas]], and [[Spanish East Indies|Asia Pacific]] when the Spanish Empire was established between the 15th and 19th centuries.<br> |

|||

Today, between 322 and 400 million people natively speak Spanish,<ref name = "universidad de Mexico">[http://209.85.135.104/search?q=cache:v5IUdEETu40J:www.lllf.uam.es/~fmarcos/coloquio/Ponencias/MMelgar.doc+%22En+el+mundo+lo+hablan+aproximadamente+400+millones+de+personas%22+%22Adicionalmente+100+millones+de+personas+hablan+espa%C3%B1ol+como+segunda+lengua%22&hl=es&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=es Universidad de México]{{Verify credibility|date=March 2008}}{{subst:Sup|(cached URL)}}<</ref><ref name="instituto cervantes">Instituto Cervantes ([http://66.102.9.104/search?q=cache:0i7Y43lUanEJ:www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2007/04/26/cultura/1177610767.html+%22Instituto+Cervantes%22%22los+actuales+500+millones+de+hispanohablantes+en+Latinoam%C3%A9rica+y+Espa%C3%B1a%22&hl=es&ct=clnk&cd=2&gl=es "El Mundo" news])</ref> making it the world's second most-spoken language by native speakers (after [[Standard Mandarin|Mandarin Chinese]]).<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/19990429232804/www.sil.org/ethnologue/top100.html Ethnologue, 1999]</ref><ref>[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2098.html CIA World Factbook], Field Listing - Languages (World).</ref> |

|||

Spanish is part of the [[Iberian Romance languages|Ibero-Romance language group]], in which the language is also known as ''Castilian'' ({{Lang|es|castellano}}). The group evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Latin in Iberia after the [[collapse of the Western Roman Empire]] in the 5th century. The oldest Latin texts with traces of Spanish come from mid-northern Iberia in the 9th century,<ref>{{Citation |last=Vergaz |first=Miguel A. |title=La RAE avala que Burgos acoge las primeras palabras escritas en castellano |date=7 November 2010 |url=http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2010/11/07/castillayleon/1289123856.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101124225541/http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2010/11/07/castillayleon/1289123856.html |place=ES |publisher=El Mundo |language=es |access-date=24 November 2010 |archive-date=24 November 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref> and the first systematic written use of the language happened in [[Toledo (Spain)|Toledo]], a prominent city of the [[Kingdom of Castile]], in the 13th century. Spanish colonialism in the [[early modern period]] spurred the introduction of the language to overseas locations, most notably to the Americas.<ref>{{cite web |last=Rice |first=John |date=2010 |title=sejours linguistiques en Espagne |url=http://sejours-linguistiques-en-espagne.com/index.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130118163355/http://sejours-linguistiques-en-espagne.com/index.html |archive-date=18 January 2013 |access-date=3 March 2022 |website=sejours-linguistiques-en-espagne.com}}</ref> |

|||

==Hispanosphere== |

|||

{{Seealso|Spanish Empire}} |

|||

As a Romance language, Spanish is a descendant of Latin. Around 75% of modern Spanish vocabulary is Latin in origin, including Latin borrowings from Ancient Greek.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Heriberto Robles |author2=Camacho Becerra |author3=Juan José Comparán Rizo |author4=Felipe Castillo |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ODJ7FTikTE0C&pg=PA19 |title=Manual de etimologías grecolatinas |date=1998 |publisher=Limusa |isbn=968-18-5542-6 |edition=3rd |location=Mexico |page=19 |access-date=9 January 2023 |archive-date=24 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230124185159/https://www.google.com/books/edition/Manual_de_etimolog%C3%ADas_grecolatinas/ODJ7FTikTE0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA19&printsec=frontcover |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Comparán Rizo |first1=Juan José |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=caqn_7i6tvkC&pg=PA17 |title=Raices Griegas y latinas |publisher=Ediciones Umbral |isbn=978-968-5430-01-2 |page=17 |language=es |access-date=22 August 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170423162130/https://books.google.com/books?id=caqn_7i6tvkC |archive-date=23 April 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> Alongside English and [[French language|French]], it is also one of the most taught foreign languages throughout the world.<ref>[https://www.languagemagazine.com/2019/11/18/spanish-in-the-world/ Spanish in the World] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210206042553/https://www.languagemagazine.com/2019/11/18/spanish-in-the-world/ |date=6 February 2021}}, ''Language Magazine'', 18 November 2019.</ref> Spanish is well represented in the [[humanities]] and [[social sciences]].<ref>{{cite news |date=5 March 2014 |title=El español se atasca como lengua científica |url=https://www.agenciasinc.es/Noticias/El-espanol-se-atasca-como-lengua-cientifica |work=Servicio de Información y Noticias Científicas |language=es |access-date=29 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190222204919/https://www.agenciasinc.es/Noticias/El-espanol-se-atasca-como-lengua-cientifica |archive-date=22 February 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> Spanish is also the third most used language on the internet by number of users after English and Chinese<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/internet-language |title=What Are The Most-Used Languages On The Internet? |work=+Babbel Magazine |last=Devlin |first=Thomas Moore |date=30 January 2019 |access-date=13 July 2021 |url-status=live |archive-date=6 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211206012715/https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/internet-language}}</ref> and the second most used language by number of websites after English.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language |title=Usage statistics of content languages for websites |date=10 February 2024 |access-date=10 February 2024 |archive-date=17 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190817192928/https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language/all/ |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right:12px;" |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Image:Map-Hispano.png|border|400px|[[Hispanic World]]]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{legend|Red|''[[Spanish language|Spanish]] identified as the sole Official language''}}{{legend|Blue|''Spanish identified as a Co-Official language''}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan="5" align="center" | <small>The Countries of the [[Hispanophone|Hispanic-influenced World]] |

|||

|} |

|||

Spanish is used as an official language by [[List of countries and territories where Spanish is an official language#International organizations|many international organizations]], including the [[United Nations]], [[European Union]], [[Organization of American States]], [[Union of South American Nations]], [[Community of Latin American and Caribbean States]], [[African Union]], among others.<ref name="un1"/> |

|||

It is estimated that the combined total of native and non-native Spanish speakers is approximately 500 million, likely making it the third most spoken language by total number of speakers (after [[English_language|English]] and [[Chinese_language|Chinese]]).<ref name = "universidad de Mexico">[http://209.85.135.104/search?q=cache:v5IUdEETu40J:www.lllf.uam.es/~fmarcos/coloquio/Ponencias/MMelgar.doc+%22En+el+mundo+lo+hablan+aproximadamente+400+millones+de+personas%22+%22Adicionalmente+100+millones+de+personas+hablan+espa%C3%B1ol+como+segunda+lengua%22&hl=es&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=es Universidad de México]{{Verify credibility|date=March 2008}}{{subst:Sup|(cached URL)}}<</ref><ref name="instituto cervantes">Instituto Cervantes ([http://66.102.9.104/search?q=cache:0i7Y43lUanEJ:www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2007/04/26/cultura/1177610767.html+%22Instituto+Cervantes%22%22los+actuales+500+millones+de+hispanohablantes+en+Latinoam%C3%A9rica+y+Espa%C3%B1a%22&hl=es&ct=clnk&cd=2&gl=es "El Mundo" news])</ref><br> |

|||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

Today, Spanish is an official language of Spain, most [[Latin American]] countries, and [[Equatorial Guinea]]; 21 nations speak it as their primary language. Spanish also is one of [[United Nations#Languages|six official languages]] of the [[United Nations]]. |

|||

[[Mexico]] has the world's largest Spanish-speaking population, and Spanish is the second most-widely spoken language in the [[United States]] <ref>[https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/us.html CIA The World Factbook United States]</ref> and the most popular studied foreign language in [[United States|U.S.]] schools and universities.<ref>{{PDFlink|[http://www.census.gov/prod/2005pubs/06statab/pop.pdf United States Census Bureau]|1.86 [[Mebibyte|MiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 1956553 bytes -->}}, Statistical Abstract of the United States: page 47: Table 47: Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2003</ref><ref>{{PDFlink|[http://www.adfl.org/resources/enrollments.pdf Foreign Language Enrollments in United States Institutions of Higher Learning]|129 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 132628 bytes -->}}, MLA Fall 2002.</ref> [[Global internet usage]] statistics for 2007 show Spanish as the third most commonly used language on the internet, after English and [[Chinese language|Chinese]].<ref>[http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm World Internet Usage Statistics]</ref>Spanish has been described as the third most influential language in the world (after [[English Language|English]] and [[French Language|French]])<ref name="TOP LANGUAGES: The world's 10 most influential languages">{{Citation |

|||

|url=http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/reprints/weber/rep-weber.htm |

|||

|title=TOP LANGUAGES: The World's 10 most influential Languages |

|||

|author=George Weber |

|||

|publisher=andaman.org |

|||

|accessdate=[[2007-12-29]]}} {{verify credibility|date=December 2007}}</ref> |

|||

== Name of the language and etymology == |

|||

==Naming,origin== |

|||

{{Main|Names given to the Spanish language}} |

|||

=== Name of the language === |

|||

In Spain and some other parts of the Spanish-speaking world, Spanish is called not only {{lang|es|[[wikt:español#Spanish|español]]}} but also {{lang|es|[[wikt:castellano#Spanish|castellano]]}} (Castilian), the language from the [[Kingdom of Castile]], contrasting it with other [[languages of Spain|languages spoken in Spain]] such as [[Galician language|Galician]], [[Basque language|Basque]], [[Asturian language|Asturian]], [[Catalan language|Catalan/Valencian]], [[Aragonese language|Aragonese]], [[Occitan language|Occitan]] and other minor languages. |

|||

The [[Spanish Constitution of 1978]] uses the term {{lang|es|castellano}} to define the [[official language]] of the whole of Spain, in contrast to {{lang|es|las demás lenguas españolas}} (lit. "the other [[languages of Spain|Spanish languages]]"). Article III reads as follows: |

|||

Castilian is the official Spanish language of the State. (…) The other Spanish languages shall also be official in their respective Autonomous Communities…}} |

|||

{{blockquote|{{lang|es|El castellano es la lengua española oficial del Estado. ... Las demás lenguas españolas serán también oficiales en las respectivas Comunidades Autónomas...}}<br /> |

|||

The name ''castellano'' is, however, widely used for the language as a whole in Latin America. Some Spanish speakers consider ''{{lang|es|castellano}}'' a generic term with no political or ideological links, much as "Spanish" is in English. Often Latin Americans use it to differentiate their own variety of Spanish as opposed to the variety of Spanish spoken in Spain, or variety of Spanish which is considered as standard in the region.{{Fact|date=October 2007}} |

|||

Castilian is the official Spanish language of the State. ... The other Spanish languages shall also be official in their respective Autonomous Communities...}} |

|||

The [[Real Academia Española|Royal Spanish Academy]] ({{Lang|es|Real Academia Española}}), on the other hand, currently uses the term {{lang|es|español}} in its publications. However, from 1713 to 1923, it called the language {{lang|es|castellano}}.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Problemas de la lengua española (I): La lengua, los niveles y la norma {{!}} Fundación Juan March |url=https://www.march.es/es/madrid/conferencia/problemas-lengua-espanola-i-lengua-niveles-norma |access-date=2024-11-07 |website=www.march.es |language=es}}</ref> |

|||

==Classification and related languages== |

|||

The {{lang|es|[[Diccionario panhispánico de dudas]]}} (a language guide published by the Royal Spanish Academy) states that, although the Royal Spanish Academy prefers to use the term {{lang|es|español}} in its publications when referring to the Spanish language, both terms—{{lang|es|español}} and {{lang|es|castellano}}—are regarded as synonymous and equally valid.<ref>Diccionario panhispánico de dudas, 2005, p. 271–272.</ref> |

|||

Spanish is closely related to the other [[West Iberian languages|West Iberian]] Romance languages: [[Asturian language|Asturian]] ({{lang|ast|''asturianu''}}), [[Galician language|Galician]] ({{lang|gl|''galego''}}), [[Ladino language|Ladino]] ({{lang|lad|''dzhudezmo/spanyol/kasteyano''}}), and [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] ({{lang|pt|''português''}}). Catalan, an [[Iberian Romance languages|East Iberian language]] which exhibits many [[Gallo-Romance]] traits, is more similar to the neighbouring [[Occitan language]] ({{lang|oc|''occitan''}}) than to Spanish, or indeed than Spanish and Portuguese are to each other. |

|||

===Etymology=== |

|||

Spanish and Portuguese share similar grammars and a majority of vocabulary as well as a common history of [[Influence of Arabic on other languages|Arabic influence]] while a great part of the peninsula was under [[Timeline of the Muslim presence in the Iberian peninsula|Islamic rule]] (both languages expanded over [[Islamic empire|Islamic territories]]). Their [[lexical similarity]] has been estimated as 89%.<ref name="ethnologue"/> See [[Differences between Spanish and Portuguese]] for further information. |

|||

The term {{lang|es|castellano}} is related to [[Kingdom of Castile|Castile]] ({{lang|es|Castilla}} or archaically {{lang|osp|Castiella}}), the kingdom where the language was originally spoken. The name ''Castile'', in turn, is usually assumed to be derived from {{lang|es|castillo}} ('castle'). |

|||

In the [[Middle Ages]], the language spoken in Castile was generically referred to as {{lang|es|Romance}} and later also as {{lang|es|Lengua vulgar}}.<ref name="espania" /> Later in the period, it gained geographical specification as {{lang|es|Romance castellano}} ({{Lang|es|romanz castellano}}, {{Lang|es|romanz de Castiella}}), {{Lang|es|lenguaje de Castiella}}, and ultimately simply as {{lang|es|castellano}} (noun).<ref name="espania">{{Cite journal|url=https://journals.openedition.org/e-spania/22518?lang=es|title=De nuevo sobre los nombres medievales de la lengua de Castilla|first=Rafael|last=Cano Aguilar|doi=10.4000/e-spania.22518|journal=E-Spania|year=2013|issue=15|access-date=7 July 2022|archive-date=7 July 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220707205518/https://journals.openedition.org/e-spania/22518?lang=es|url-status=live|doi-access=free| issn = 1951-6169}}</ref> |

|||

===Ladino=== |

|||

{{further|[[Ladino language]]}} |

|||

Different etymologies have been suggested for the term {{lang|es|español}} (Spanish). According to the Royal Spanish Academy, {{lang|es|español}} derives from the [[Occitan language|Occitan]] word {{Lang|oc|espaignol}} and that, in turn, derives from the [[Vulgar Latin]] *{{lang|la|hispaniolus}} ('of Hispania').<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dle.rae.es/?id=GUSX1EQ |title=español, la |work=Diccionario de la lengua española |publisher=Real Academia Espańola |access-date=13 July 2021 |url-status=live |archive-date=24 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170424193620/http://dle.rae.es/?id=GUSX1EQ}}</ref> [[Hispania]] was the Roman name for the entire [[Iberian Peninsula]]. |

|||

Ladino, which is essentially medieval Spanish and closer to modern Spanish than any other language, is spoken by many descendants of the [[Sephardi Jews]] who were [[Alhambra decree|expelled from Spain in the 15th century]]. Ladino speakers are currently almost exclusively [[Sephardim|Sephardi]] Jews, with family roots in Turkey, Greece or the Balkans: current speakers mostly live in Israel and Turkey, with a few pockets in Latin America. In many ways it is not a separate language but a parallel dialect of Castilian. It lacks the [[Amerindian languages|Native American vocabulary]] which was influential during the [[Spanish Empire|Spanish colonial period]], and it retains many archaic features which have since been lost in standard Spanish. It contains, however, other vocabulary which is not found in standard Castilian, including vocabulary from [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]], some French, Greek and [[Turkish language|Turkish]], and other languages spoken where the Sephardim settled. |

|||

There are other hypotheses apart from the one suggested by the Royal Spanish Academy. Spanish philologist [[Ramón Menéndez Pidal]] suggested that the classic {{lang|la|hispanus}} or {{lang|la|hispanicus}} took the suffix {{Lang|la|-one}} from [[Vulgar Latin]], as happened with other words such as {{lang|es|bretón}} (Breton) or {{lang|es|sajón}} (Saxon). |

|||

Ladino is in serious danger of extinction because many native speakers today are elderly as well as elderly ''olim'' (immigrants to [[Israel]]) who have not transmitted the language to their children or grandchildren. However, it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardi communities, especially in music. In the case of the Latin American communities, the danger of extinction is also due to the risk of assimilation by modern Castilian. |

|||

== History == |

|||

A related dialect is [[Haketia]], the Judaeo-Spanish of northern Morocco. This too tended to assimilate with modern Spanish, during the Spanish occupation of the region. |

|||

{{Main|History of the Spanish language}} |

|||

[[File:CartulariosValpuesta.jpg|right|thumb|The Visigothic [[Cartularies of Valpuesta]], written in a late form of Latin, were declared in 2010 by the Royal Spanish Academy as the record of the earliest words written in Castilian, predating those of the [[Glosas Emilianenses]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.euskonews.com/udalak/valpuesta/cartularioshistoria.htm|title=cartularioshistoria|website=www.euskonews.com|access-date=22 September 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160402124945/http://www.euskonews.com/udalak/valpuesta/cartularioshistoria.htm|archive-date=2 April 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref>]] |

|||

===Vocabulary comparison=== |

|||

Like the other [[Romance language]]s, the Spanish language evolved from [[Vulgar Latin]], which was brought to the [[Iberian Peninsula]] by the [[Roman Republic|Romans]] during the [[Second Punic War]], beginning in 210 BC. Several pre-Roman languages (also called [[Paleohispanic languages]])—some distantly related to Latin as [[Indo-European language]]s, and some that are not related at all—were previously spoken in the Iberian Peninsula. These languages included [[Proto-Basque language|Proto-Basque]], [[Iberian language|Iberian]], [[Lusitanian language|Lusitanian]], [[Celtiberian language|Celtiberian]] and [[Gallaecian language|Gallaecian]]. |

|||

Spanish and [[Italian language|Italian]] share a very similar phonological system and do not differ very much in grammar. At present, the [[lexical similarity]] with Italian is estimated at 82%.<ref name="ethnologue"/> As a result, Spanish and Italian are mutually intelligible to various degrees. The lexical similarity with [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] is even greater, 89%, but the vagaries of Portuguese pronunciation make it less easily understood by Hispanophones than Italian. [[Mutual intelligibility]] between Spanish and [[French language|French]] or [[Romanian language|Romanian]] is even lower (lexical similarity being respectively 75% and 71%<ref name="ethnologue"/>): comprehension of Spanish by French speakers who have not studied the language is as low as an estimated 45% - the same as of English. The common features of the writing systems of the Romance languages allow for a greater amount of interlingual reading comprehension than oral communication would. |

|||

The first documents to show traces of what is today regarded as the precursor of modern Spanish are from the 9th century. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the [[modern era]], the most important [[Language contact|influence]]s on the Spanish lexicon came from neighboring [[Romance languages]]—[[Mozarabic language|Mozarabic]] ([[Andalusi Romance]]), [[Navarro-Aragonese]], [[Leonese language|Leonese]], [[Catalan language|Catalan/Valencian]], [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], [[Galician language|Galician]], [[Occitan language|Occitan]], and later, [[French language|French]] and [[Italian language|Italian]]. Spanish also [[Loanword|borrowed]] a considerable number of words from [[Arabic language|Arabic]], as well as a minor influence from the Germanic [[Gothic language]] through the period of [[Visigoth]] rule in Iberia. In addition, many more words were borrowed from [[Latin language|Latin]] through the influence of written language and the liturgical language of the Church. The loanwords were taken from both [[Classical Latin]] and [[Renaissance Latin]], the form of Latin in use at that time. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

According to the theories of [[Ramón Menéndez Pidal]], local [[sociolect]]s of Vulgar Latin evolved into Spanish, in the north of Iberia, in an area centered in the city of [[Burgos]], and this dialect was later brought to the city of [[Toledo (Spain)|Toledo]], where the written standard of Spanish was first developed, in the 13th century.<ref name="Penny1p16">{{Harvcoltxt|Penny|2000|p=16}}</ref> In this formative stage, Spanish developed a strongly differing variant from its close cousin, [[Leonese language|Leonese]], and, according to some authors, was distinguished by a heavy Basque influence (see [[Iberian Romance languages]]). This distinctive dialect spread to southern Spain with the advance of the {{lang|es|[[Reconquista]]}}, and meanwhile gathered a sizable lexical influence from the [[Arabic language|Arabic]] of [[Al-Andalus]], much of it indirectly, through the Romance [[Mozarabic language|Mozarabic dialects]] (some 4,000 [[Arabic language|Arabic]]-derived words, make up around 8% of the language today).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O29-SPANISH.html|title=Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language|publisher=Oxford University Press|access-date=24 July 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080925062202/http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O29-SPANISH.html|archive-date=25 September 2008|url-status=live}}</ref> The written standard for this new language was developed in the cities of [[Toledo, Spain|Toledo]], in the 13th to 16th centuries, and [[Madrid]], from the 1570s.<ref name="Penny1p16" /> |

|||

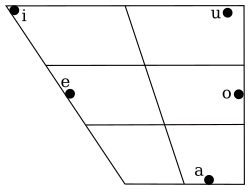

The development of the [[Spanish phonology|Spanish sound system]] from that of [[Vulgar Latin]] exhibits most of the changes that are typical of [[Western Romance languages]], including [[lenition]] of intervocalic consonants (thus Latin {{lang|la|vīta}} > Spanish {{lang|es|vida}}). The [[Vowel breaking|diphthongization]] of Latin stressed short {{Lang|la|e}} and {{Lang|la|o}}—which occurred in [[Syllable coda|open syllables]] in French and Italian, but not at all in Catalan or Portuguese—is found in both open and closed syllables in Spanish, as shown in the following table: |

|||

<div style="overflow: auto;"> |

|||

<!-- The words in each cell are tagged with the first language whose column intersects the cell. --> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" |

|||

! Latin || Spanish || Ladino || Aragonese || Asturian || Galician || Portuguese || Catalan || Gascon / Occitan || French || Sardinian || Italian || Romanian || |English |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{smallcaps|petra}} || colspan="4" | {{lang|es|p'''ie'''dra}} || colspan="3" | {{lang|gl|pedra}} || {{lang|oc|pedra}}, {{lang|oc|pèira}} || {{lang|fr|p'''ie'''rre}} ||''pedra'', {{lang|sc|perda}}||{{lang|it|p'''ie'''tra}} || {{lang|ro|p'''ia'''tră}} || 'stone' |

|||

! [[Latin]] |

|||

! [[Spanish language|Spanish]] |

|||

! [[Galician language|Galician]] |

|||

! [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] |

|||

! [[Catalan language|Catalan]] |

|||

! [[Italian language|Italian]] |

|||

! [[French language|French]] |

|||

! [[Romanian language|Romanian]] |

|||

! [[English language|English]] Meaning and notes |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|la|''nos''}} |

|||

| {{lang|es|''nos'''otros'''''}} |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''nós''}}/{{lang|gl|''nosoutros''}} |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''nós''}}<sup>¹</sup> |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''nos'''altres'''''}} |

|||

| {{lang|it|''noi''}}<sup>²</sup> |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''nous''}}<sup>³</sup> |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''noi''}} |

|||

| we[-'''others'''] |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|la|''fratrem germānum'' (acc.)}} (lit. "true brother", i.e. not a cousin) |

|||

| {{lang|es|''hermano''}} |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''irmán''}} |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''irmão''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''germà''}} |

|||

| {{lang|it|''fratello''}} |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''frère''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''frate''}} |

|||

| brother |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|la|''dies Martis''}} <br/> ([[Classical Latin|Classical]]) |

|||

{{lang|la|''tertia feria''}} <br /> ([[Ecclesiastical Latin|Ecclesiastical]]) |

|||

| {{lang|es|''martes''}} |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''martes''}} |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''terça-feira''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''dimarts''}} |

|||

| {{lang|it|''martedì''}} |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''mardi''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''marți''}} |

|||

| Tuesday |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{smallcaps|terra}} || colspan="4" | {{lang|es|t'''ie'''rra}} || colspan="3" | {{lang|gl|terra}} || {{lang|oc|tèrra}} || {{lang|fr|terre}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|sc|terra}} || {{lang|ro|țară}} || 'land' |

|||

| {{lang|la|''cantiō'' (''nem'', acc.), ''canticum''}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|es|''canción''}} |

|||

| {{smallcaps|moritur}} || colspan="3" | {{lang|es|m'''ue'''re}} || {{lang|ast|m'''ue'''rre}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|gl|morre}} || {{lang|ca|mor}} || {{lang|oc|morís}} || {{lang|fr|m'''eu'''rt}} || {{lang|sc|mòrit}} || {{lang|it|m'''uo'''re}} || {{lang|ro|m'''oa'''re}} || 'dies (v.)' |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''canción''}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''canção''}} |

|||

| {{smallcaps|mortem}} || colspan="4" | {{lang|es|m'''ue'''rte}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|ast|morte}} || {{lang|ca|mort}} || {{lang|oc|mòrt}} || {{lang|fr|mort}} ||''morte, morti''||{{lang|it|morte}} || {{lang|ro|m'''oa'''rte}} || 'death' |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''cançó''}} |

|||

|}</div> |

|||

| {{lang|it|''canzone''}} |

|||

[[File:Linguistic map Southwestern Europe.gif|thumb|Chronological map showing linguistic evolution in southwest Europe]] |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''chanson''}} |

|||

Spanish is marked by [[Palatalization (sound change)|palatalization]] of the Latin double consonants ([[geminate]]s) {{lang|la|nn}} and {{lang|la|ll}} (thus Latin |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''cântec''}} |

|||

{{lang|la|annum}} > Spanish {{lang|es|año}}, and Latin {{lang|la|anellum}} > Spanish |

|||

| song |

|||

{{lang|es|anillo}}). |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|la|''magis''}} or {{lang|la|''plus''}} |

|||

| {{lang|es|''más''}} <br /> (archaically also {{lang|es|''plus''}}) |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''máis''}} |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''mais''}} <br /> (archaically also {{lang|pt|''chus''}}) |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''més''}} <br /> (archaically also {{lang|ca|''pus''}}) |

|||

| {{lang|it|''più''}} |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''plus''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''mai''}} |

|||

| more |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|la|''manum sinistram'' (acc.)}} |

|||

| {{lang|es|''mano izquierda''}} |

|||

also ({{lang|es|''mano siniestra''}}) |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''man esquerda''}} |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''mão esquerda''}} <br /> (archaically also {{lang|pt|''sẽestra''}}) |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''mà esquerra''}} |

|||

| {{lang|it|''mano sinistra''}} |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''main gauche''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''mâna stângă''}} |

|||

| left hand |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{lang|la|''nihil''}} or {{lang|la|''nullam rem natam'' (acc.)}} <br /> (lit. "no thing born") |

|||

| {{lang|es|''nada''}} |

|||

| {{lang|gl|''nada''}}/{{lang|gl|''ren''}} |

|||

| {{lang|pt|''nada''}} <br /> (archaically also {{lang|pt|''rem''}}) |

|||

| {{lang|ca|''res''}} |

|||

| {{lang|it|''niente''}}/{{lang|it|''nulla''}} |

|||

| {{lang|fr|''rien''}}/{{lang|fr|''nul''}} |

|||

| {{lang|ro|''nimic''}} |

|||

| nothing |

|||

|} |

|||

The consonant written {{lang|la|u}} or {{lang|la|v}} in Latin and pronounced {{IPA|[w]}} in Classical Latin had probably "[[Fortition|fortified]]" to a bilabial fricative {{IPA|/β/}} in Vulgar Latin. In early Spanish (but not in Catalan or Portuguese) it merged with the consonant written ''b'' (a bilabial with plosive and fricative allophones). In modern Spanish, there is [[betacism|no difference]] between the pronunciation of orthographic {{lang|es|b}} and {{lang|es|v}}. |

|||

<small> |

|||

1. also {{lang|pt|''nós outros''}} in early modern Portuguese (e.g. ''[[The Lusiads]]'')<br> |

|||

2. {{lang|it|''noi '''altri'''''}} in Southern [[List of languages of Italy|Italian dialects and languages]]<br> |

|||

3. Alternatively {{lang|fr|''nous '''autres'''''}} |

|||

</small> |

|||

Typical of Spanish (as also of neighboring [[Gascon language|Gascon]] extending as far north as the [[Gironde estuary]], and found in a small area of [[Calabria]]), attributed by some scholars to a Basque [[Substrata (linguistics)|substratum]] was the mutation of Latin initial {{lang|la|f}} into {{lang|es|h-}} whenever it was followed by a vowel that did not diphthongize. The {{lang|es|h-}}, still preserved in spelling, is now silent in most varieties of the language, although in some Andalusian and Caribbean dialects, it is still aspirated in some words. Because of borrowings from Latin and neighboring Romance languages, there are many {{lang|es|f}}-/{{lang|es|h}}- [[Doublet (linguistics)|doublet]]s in modern Spanish: {{lang|es|Fernando}} and {{lang|es|Hernando}} (both Spanish for "Ferdinand"), {{lang|es|ferrero}} and {{lang|es|herrero}} (both Spanish for "smith"), {{lang|es|fierro}} and {{lang|es|hierro}} (both Spanish for "iron"), and {{lang|es|fondo}} and {{lang|es|hondo}} (both words pertaining to depth in Spanish, though {{lang|es|fondo}} means "bottom", while {{lang|es|hondo}} means "deep"); additionally, {{lang|es|hacer}} ("to make") is [[cognate]] to the root word of {{lang|es|satisfacer}} ("to satisfy"), and {{lang|es|hecho}} ("made") is similarly cognate to the root word of {{lang|es|satisfecho}} ("satisfied"). |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{main|History of the Spanish language}} |

|||

[[Image:Page of Lay of the Cid.jpg|thumb|A page of {{lang|es|''[[Cantar de Mio Cid]]''}}, in medieval Castilian.]] |

|||

Compare the examples in the following table: |

|||

Spanish evolved from [[Vulgar Latin]], with minor [[Arabic influence on the Spanish language|influences from Arabic]] during the [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] period and from [[Basque language|Basque]] and [[Celtiberian language|Celtiberian]], and some [[Germanic languages]] via the [[Visigoths]]. Spanish developed along the remote cross road strips among the [[Alava]], [[Cantabria]], [[Burgos]], [[Soria]] and [[La Rioja (autonomous community)|La Rioja]] provinces of Northern Spain, as a strongly innovative and differing variant from its nearest cousin, [[Asturian|Leonese speech]], with a higher degree of Basque influence in these regions (see [[Iberian Romance languages]]). Typical features of Spanish diachronical [[phonology]] include [[lenition]] (Latin {{lang|la|''vita''}}, Spanish {{lang|es|''vida''}}), [[palatalization]] (Latin {{lang|la|''annum''}}, Spanish {{lang|es|''año''}}, and Latin {{lang|la|''anellum''}}, Spanish {{lang|es|''anillo''}}) and [[diphthong]]ation ([[stem (linguistics)|stem]]-changing) of short ''e'' and ''o'' from Vulgar Latin (Latin {{lang|la|''terra''}}, Spanish {{lang|es|''tierra''}}; Latin {{lang|la|''novus''}}, Spanish {{lang|es|''nuevo''}}). Similar phenomena can be found in other Romance languages as well. |

|||

<div style="overflow: auto;"> |

|||

<!-- The words in each cell are tagged with the first language whose column intersects the cell. --> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" |

|||

! Latin || Spanish || Ladino || Aragonese || Asturian || Galician || Portuguese || Catalan || Gascon / Occitan || French || Sardinian || Italian || Romanian || English |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|filium}} || {{lang|es|'''h'''ijo}} || {{lang|lad|fijo}} (or {{lang|lad|hijo}}) || {{lang|an|fillo}} || {{lang|ast|fíu}} || {{lang|gl|fillo}} || {{lang|pt|filho}} || {{lang|ca|fill}} || {{lang|oc|filh}}, {{lang|oc|'''h'''ilh}} || {{lang|fr|fils}} ||''fizu, fìgiu, fillu''||{{lang|it|figlio}} || {{lang|ro|fiu}} || 'son' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|facere}} || {{lang|es|'''h'''acer}} || {{lang|lad|fazer}} || {{lang|an|fer}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|ast|facer}} || {{lang|pt|fazer}} || {{lang|ca|fer}} || {{lang|oc|far}}, {{lang|oc|faire}}, {{lang|oc|'''h'''ar}} (or {{lang|oc|'''h'''èr}}) || {{lang|fr|faire}} ||''fàghere, fàere, {{lang|sc|fàiri}}''||{{lang|it|fare}} || {{lang|ro|a face}} || 'to do' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|febrem}} || colspan="4" | {{lang|es|fiebre}} ''(calentura)''|| colspan="3" |{{lang|gl|febre}} || {{lang|oc|fèbre}}, {{lang|oc|frèbe}}, {{lang|oc|'''h'''rèbe}} (or<br />{{lang|oc|'''h'''erèbe}}) || {{lang|fr|fièvre}} ||{{lang|sc|calentura}}||{{lang|it|febbre}} || {{lang|ro|febră}} || 'fever' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|focum}} || colspan="3" | {{lang|es|fuego}} || {{lang|ast|fueu}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|gl|fogo}} || {{lang|ca|foc}} || {{lang|oc|fuòc}}, {{lang|oc|fòc}}, {{lang|oc|'''h'''uèc}} || {{lang|fr|feu}} || {{lang|sc|fogu}} || {{lang|it|fuoco}} || {{lang|ro|foc}} || 'fire' |

|||

|}</div> |

|||

Some [[consonant cluster]]s of Latin also produced characteristically different results in these languages, as shown in the examples in the following table: |

|||

<div style="overflow: auto;"> |

|||

<!-- The words in each cell are tagged with the first language whose column intersects the cell. --> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" |

|||

! Latin || Spanish || Ladino || Aragonese || Asturian || Galician || Portuguese || Catalan || Gascon / Occitan || French || Sardinian || Italian || Romanian || English |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|'''cl'''āvem}} || {{lang|es|'''ll'''ave}} || {{lang|lad|clave}} || {{lang|an|clau}} || {{lang|ast|'''ll'''ave}} || {{lang|gl|chave}} || {{lang|pt|chave}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|ca|clau}} || {{lang|fr|clé}} ||''giae, crae,'' {{lang|sc|crai}}||{{lang|it|chiave}} || {{lang|ro|cheie}} || 'key' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|'''fl'''amma}} || {{lang|es|'''ll'''ama}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|lad|'''fl'''ama}} || {{lang|ast|chama}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|gl|chama}}, {{lang|gl|flama}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|ca|flama}} || {{lang|fr|flamme}} || {{lang|sc|framma}} || {{lang|it|fiamma}} || {{lang|ro|flamă}} || 'flame' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|'''pl'''ēnum}} || {{lang|es|'''ll'''eno}} || {{lang|lad|pleno}} || {{lang|an|plen}} || {{lang|ast|'''ll'''enu}} || {{lang|gl|cheo}} || {{lang|pt|cheio}}, {{lang|pt|pleno}} || {{lang|ca|ple}} || {{lang|oc|plen}} || {{lang|fr|plein}} || {{lang|sc|prenu}} || {{lang|it|pieno}} || {{lang|ro|plin}} || 'plenty, full' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|o'''ct'''ō}} || colspan="2" | {{lang|es|o'''ch'''o}} || {{lang|an|güeito}} || {{lang|ast|o'''ch'''o}}, {{lang|ast|oito}} || {{lang|gl|oito}} || {{lang|pt|oito}} ({{lang|pt|oi'''t'''o}}) || {{lang|ca|vuit}}, {{lang|ca|huit}} || {{lang|oc|uè'''ch'''}}, {{lang|oc|uò'''ch'''}}, {{lang|oc|uèit}} || {{lang|fr|huit}} || {{lang|sc|oto}}||{{lang|it|otto}} || {{lang|ro|opt}} || 'eight' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{smallcaps|mu'''lt'''um}} || {{lang|es|mu'''ch'''o}}<br />{{lang|es|mu'''y'''}} || {{lang|lad|mu'''nch'''o}}<br />{{lang|lad|mu'''y'''}} || {{lang|an|muito}}<br />{{lang|an|mu'''i'''}} || {{lang|ast|mu'''nch'''u}}<br />{{lang|ast|mu'''i'''}} || {{lang|gl|moito}}<br />{{lang|gl|mo'''i'''}} ||''muito'' ||{{lang|ca|molt}} || {{lang|oc|molt}} (arch.) ||{{lang|fr|très}}, {{lang|fr|beaucoup}}, {{lang|fr|moult}} |

|||

|{{lang|sc|meda}}||{{lang|it|molto}} || {{lang|ro|mult}} || 'much,<br />very,<br />many' |

|||

|}</div> |

|||

[[File:Juan de Zúñiga dibujo con orla (cropped).jpg|thumb|upright|[[Antonio de Nebrija]], author of {{lang|es|[[Gramática de la lengua castellana]]}}, the first grammar of a modern European language<ref>{{cite news |url=http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,1105510,00.html |title=Harold Bloom on Don Quixote, the first modern novel | Books | The Guardian |publisher=Books.guardian.co.uk |date=12 December 2003 |access-date=18 July 2009 |location=London |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080614054652/http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,1105510,00.html |archive-date=14 June 2008 |url-status=dead}}</ref>]] |

|||

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spanish underwent a dramatic change in the pronunciation of its [[sibilant consonants]], known in Spanish as the {{lang|es|[[:es:Reajuste de las sibilantes del idioma español|reajuste de las sibilantes]]}}, which resulted in the distinctive [[velar]] {{IPA|[x]}} pronunciation of the letter {{angle bracket|j}} and—in a large part of Spain—the characteristic [[Interdental consonant|interdental]] {{IPA|[θ]}} ("th-sound") for the letter {{angle bracket|z}} (and for {{angle bracket|c}} before {{angle bracket|e}} or {{angle bracket|i}}). See [[History of Spanish#Modern development of the Old Spanish sibilants|History of Spanish (Modern development of the Old Spanish sibilants)]] for details. |

|||

During the {{lang|es|''[[Reconquista]]''}}, this northern dialect from [[Cantabria]] was carried south, and remains a [[minority language]] in the northern coastal [[Morocco]]. |

|||

The {{lang|es|[[Gramática de la lengua castellana]]}}, written in [[Salamanca]] in 1492 by [[Antonio de Nebrija|Elio Antonio de Nebrija]], was the first grammar written for a modern European language.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Spanish_language.aspx#1O29-SPANISH |title=Spanish Language Facts |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia.com |access-date=6 November 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110522190202/http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Spanish_language.aspx#1O29-SPANISH |archive-date=22 May 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> According to a popular anecdote, when Nebrija presented it to [[Isabella I of Castile|Queen Isabella I]], she asked him what was the use of such a work, and he answered that language is the instrument of empire.<ref>{{cite book |last=Crow |first=John A. |title=Spain: the root and the flower |page=151 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g2NKy8QCxw4C&q=Nebrija+first+spanish+grammar+Isabel&pg=PA151 |year=2005 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-24496-2 |access-date=28 October 2020 |archive-date=17 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817150949/https://books.google.com/books?id=g2NKy8QCxw4C&q=Nebrija+first+spanish+grammar+Isabel&pg=PA151 |url-status=live}}</ref> In his introduction to the grammar, dated 18 August 1492, Nebrija wrote that "... language was always the companion of empire."<ref>{{cite book |last=Thomas |first=Hugh |title=Rivers of Gold: the rise of the Spanish empire, from Columbus to Magellan |page=78 |year=2005 |publisher=Random House Inc. |isbn=978-0-8129-7055-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=b38f7b1WmOwC&q=Nebrija+first+spanish+grammar+Isabel&pg=PA78 |access-date=28 October 2020 |archive-date=16 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210816174720/https://books.google.com/books?id=b38f7b1WmOwC&q=Nebrija+first+spanish+grammar+Isabel&pg=PA78 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The first Latin-to-Spanish grammar ({{lang|es|''Gramática de la Lengua Castellana''}}) was written in [[Salamanca]], Spain, in 1492, by [[Antonio de Nebrija|Elio Antonio de Nebrija]]. When it was presented to [[Isabel de Castilla]], she asked, "What do I want a work like this for, if I already know the language?", to which he replied, "Your highness, the language is the instrument of the Empire." {{Fact|date=August 2007}} |

|||

From the 16th century onwards, the language was taken to the [[Americas]] and the [[Spanish East Indies]] via [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish colonization]], |

From the 16th century onwards, the language was taken to the Spanish-discovered [[Americas|America]] and the [[Spanish East Indies]] via [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish colonization of America]]. [[Miguel de Cervantes]], author of ''[[Don Quixote]]'', is such a well-known reference in the world that Spanish is often called {{lang|es|la lengua de Cervantes}} ("the language of Cervantes").<ref>{{cite web|title=La lengua de Cervantes |language=es |url=http://www.cepc.es/rap/Publicaciones/Revistas/2/REP_031-032_288.pdf |publisher=Ministerio de la Presidencia de España |access-date=24 August 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081003083955/http://www.cepc.es/rap/Publicaciones/Revistas/2/REP_031-032_288.pdf |archive-date=3 October 2008}}</ref> |

||

In the 20th century, Spanish was introduced to [[Equatorial Guinea]] and the [[Western Sahara]], the United States, such as |

In the 20th century, Spanish was introduced to [[Equatorial Guinea]] and the [[Western Sahara]], and to areas of the United States that had not been part of the Spanish Empire, such as [[Spanish Harlem]] in [[New York City]]. For details on borrowed words and other external influences upon Spanish, see [[Influences on the Spanish language]]. |

||

== Geographical distribution == |

|||

===Characterization=== |

|||

{{See also|Hispanophone}} |

|||

[[File:El español en el mundo 2023 (Anuario del Instituto Cervantes).svg|thumb|Geographical distribution of the Spanish language |

|||

{{legend|#ff0000ff|Official or co-official language}} |

|||

{{legend|#ffcd48ff|Important minority (more than 25%) or majority language, but not official}} |

|||

{{legend|#ffeeaaff|Notable minority language (less than 25% but more than 500,000 Spanish speakers)}}]] |

|||

Spanish is the primary language in 20 countries worldwide. As of 2023, it is estimated that about 486 million people speak Spanish as a [[native language]], making it the second [[List of languages by number of native speakers|most spoken language by number of native speakers]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Anuario instituto Cervantes 2023 |url=https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/anuario/anuario_23/ |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=Centro Virtual Cervantes |language=es |archive-date=2023-02-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230222190339/https://www.bergesinstitutespanish.com/spanish-native-speakers |url-status=live}} Estimate. Corrected as Equatorial Guinea is mistakenly included (no native speakers there)</ref> An additional 75 million speak Spanish as a second or [[Spanish as a foreign language|foreign language]], making it the fourth [[List of languages by total number of speakers|most spoken language in the world overall]] after English, Mandarin Chinese, and Hindi with a total number of 538 million speakers.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/statistics/size|title=Summary by language size|website=Ethnologue|date=3 October 2018|access-date=14 November 2020|archive-date=26 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181226040016/https://www.ethnologue.com/statistics/size|url-status=live}}</ref> Spanish is also the third [[Languages used on the Internet|most used language on the Internet]], after English and Chinese.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm |title=Internet World Users by Language |year=2008 |publisher=Miniwatts Marketing Group |access-date=20 November 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120426122721/http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm |archive-date=26 April 2012 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

A defining characteristic of Spanish was the [[diphthong]]ization of the Latin short vowels ''e'' and ''o'' into ''ie'' and ''ue'', respectively, when they were stressed. Similar [[sound law|sound changes]] are found in other Romance languages, but in Spanish they were significant. Some examples: |

|||

=== Europe === |

|||

* Lat. {{lang|la|''petra''}} > Sp. {{lang|es|''piedra''}}, It. {{lang|it|''pietra''}}, Fr. {{lang|fr|''pierre''}}, Port./Gal. {{lang|pt|''pedra''}} "stone". |

|||

{{main|Peninsular Spanish}} |

|||

* Lat. {{lang|la|''moritur''}} > Sp. {{lang|es|''muere''}}, It. {{lang|it|''muore''}}, Fr. {{lang|fr|''meurt''}} / {{lang|fr|''muert''}}, Rom. {{lang|ro|''moare''}}, Port./Gal. {{lang|pt|''morre''}} "die". |

|||

[[File:Knowledge of Spanish in European Union.svg|thumb|Percentage of people who self reportedly know enough Spanish to hold a conversation, in the EU, 2005 |

|||

{{legend|#554400|Native country}} |

|||

{{legend|#AA8800|More than 8.99%}} |

|||

{{legend|#E5B700|Between 4% and 8.99%}} |

|||

{{legend|#FFDD55|Between 1% and 3.99%}} |

|||

{{legend|#FFEEAA|Less than 1%}}]] |

|||

Spanish is the official language of [[Spain]]. Upon the emergence of the [[Castilian Crown]] as the dominant power in the Iberian Peninsula by the end of the Middle Ages, the Romance vernacular associated with this polity became increasingly used in instances of prestige and influence, and the distinction between "Castilian" and "Spanish" started to become blurred.<ref>{{Cite book|first=Clara|last=Mar-Molinero|title=The Politics of Language in the Spanish-Speaking World|year=2000|isbn=0-203-44372-1|location=London|publisher=[[Routledge]]|pages=19–20}}</ref> Hard policies imposing the language's hegemony in an intensely centralising Spanish state were established from the 18th century onward.{{Sfn|Mar-Molinero|2000|p=21}} |

|||

Peculiar to early Spanish (as in the [[Gascon]] dialect of Occitan, and possibly due to a Basque [[substratum]]) was the mutation of Latin initial ''f-'' into ''h-'' whenever it was followed by a vowel that did not diphthongate. Compare for instance: |

|||

Other European territories in which it is also widely spoken include [[Gibraltar]] and [[Andorra]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3164.htm |title=Background Note: Andorra |publisher=U.S. Department of State: Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs |date=January 2007 |access-date=20 August 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170122194318/https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3164.htm |archive-date=22 January 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

* Lat. {{lang|la|''filium''}} > It. {{lang|it|''figlio''}}, Port. {{lang|pt|''filho''}}, Gal. {{lang|gl|''fillo''}}, Fr. {{lang|fr|''fils''}}, Occitan {{lang|oc|''filh''}} (but Gascon {{lang|gsc|''hilh''}}) Sp. {{lang|es|''hijo''}} (but Ladino {{lang|lad|''fijo''}}); |

|||

* late Lat. {{lang|la|''*fabulare''}} > Lad. {{lang|lad|''favlar''}}, Port./Gal. {{lang|pt|''falar''}}, Sp. {{lang|es|''hablar''}}; |

|||

* but Lat. {{lang|la|''focum''}} > It. {{lang|it|''fuoco''}}, Port./Gal. {{lang|pt|''fogo''}}, Sp./Lad. {{lang|es|''fuego''}}. |

|||

Spanish is also spoken by immigrant communities in other European countries, such as the [[United Kingdom]], [[France]], [[Italy]], and [[Germany]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/languages/european_languages/languages/spanish.shtml |title=BBC Education — Languages Across Europe — Spanish |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |access-date=20 August 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120929052158/http://www.bbc.co.uk/languages/european_languages/languages/spanish.shtml |archive-date=29 September 2012 |url-status=live}}</ref> Spanish is an official language of the [[European Union]]. |

|||

Some [[consonant cluster]]s of Latin also produced characteristically different results in these languages, for example: |

|||

=== Americas === |

|||

* Lat. {{lang|la|''clamare''}}, acc. {{lang|la|''flammam''}}, {{lang|la|''plenum''}} > Lad. {{lang|lad|''lyamar''}}, {{lang|lad|''flama''}}, {{lang|lad|''pleno''}}; Sp. {{lang|es|''llamar''}}, {{lang|es|''llama''}}, {{lang|es|''lleno''}}. However, in Spanish there are also the forms {{lang|la|''clamar''}}, {{lang|lad|''flama''}}, {{lang|lad|''pleno''}}; Port. {{lang|pt|''chamar''}}, {{lang|pt|''chama''}}, {{lang|pt|''cheio''}}; Gal. {{lang|gl|''chamar''}}, {{lang|gl|''chama''}}, {{lang|gl|''cheo''}}. |

|||

==== Hispanic America ==== |

|||

* Lat. acc. {{lang|la|''octo''}}, {{lang|la|''noctem''}}, {{lang|la|''multum''}} > Lad. {{lang|lad|''ocho''}}, {{lang|lad|''noche''}}, {{lang|lad|''muncho''}}; Sp. {{lang|es|''ocho''}}, {{lang|es|''noche''}}, {{lang|es|''mucho''}}; Port. {{lang|pt|''oito''}}, {{lang|pt|''noite''}}, {{lang|pt|''muito''}}; Gal. {{lang|gl|''oito''}}, {{lang|gl|''noite''}}, {{lang|gl|''moito''}}. |

|||

{{main|Spanish language in the Americas}} |

|||

Today, the majority of the Spanish speakers live in [[Hispanic America]]. Nationally, Spanish is the official language—either ''[[de facto]]'' or ''[[de jure]]''—of [[Argentina]], [[Bolivia]] (co-official with 36 indigenous languages), [[Chile]], [[Colombia]], [[Costa Rica]], [[Cuba]], [[Dominican Republic]], [[Ecuador]], [[El Salvador]], [[Guatemala]], [[Honduras]], [[Mexico]] (co-official with 63 indigenous languages), [[Nicaragua]], [[Panama]], [[Paraguay]] (co-official with [[Guarani language|Guaraní]]),<ref>[http://www.constitution.org/cons/paraguay.htm Constitución de la República del Paraguay] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140908185557/http://www.constitution.org/cons/paraguay.htm |date=8 September 2014}}, Article 140</ref> [[Peru]] (co-official with [[Quechua language|Quechua]], [[Aymara language|Aymara]], and "the other indigenous languages"),<ref>[http://www.constitucionpoliticadelperu.com/ Constitución Política del Perú] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140517192115/http://constitucionpoliticadelperu.com/ |date=17 May 2014}}, Article 48</ref> [[Puerto Rico]] (co-official with English),<ref>{{cite news |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CE1D8163AF93AA15752C0A965958260&n=Top%2fReference%2fTimes%20Topics%2fSubjects%2fE%2fEnglish%20Language |title=Puerto Rico Elevates English |date=29 January 1993 |work=the New York Times |access-date=6 October 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080122011853/http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CE1D8163AF93AA15752C0A965958260&n=Top%2FReference%2FTimes%20Topics%2FSubjects%2FE%2FEnglish%20Language |archive-date=22 January 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> [[Uruguay]], and [[Venezuela]]. |

|||

====United States==== |

|||

==Geographic distribution== |

|||

{{Main|Spanish language in the United States}} |

|||

{{main|Hispanophone}} |

|||

{{See also|Spanish language in California|New Mexican Spanish|Isleño Spanish}} |

|||

{{Spanish}} |

|||

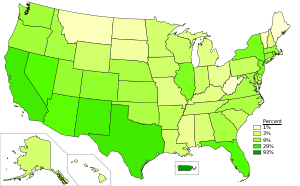

[[File:Spanish spoken at home in the United States 2019.svg|thumb|upright=1.35|right|Percentage of the U.S. population aged 5 and over who speaks Spanish at home in 2019, by states]] |

|||

Spanish language has a long history in the territory of the current-day United States dating back to the 16th century.{{Sfn|Lamboy|Salgado-Robles|2020|p=1}} In the wake of the [[Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo|1848 Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty]], hundreds of thousands of Spanish speakers became a minoritized community in the United States.{{Sfn|Lamboy|Salgado-Robles|2020|p=1}} The 20th century saw further massive growth of Spanish speakers in areas where they had been hitherto scarce.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Spanish across Domains in the United States. Education, Public Space, and Social Media|editor-first=Francisco|editor-last=Salgado-Robles|editor-first2=Edwin M.|editor-last2=Lamboy|publisher=[[Brill (publisher)|Brill]]|isbn=978-90-04-43322-9|year=2020|location=Leiden|page=1|first1=Edwin M.|last1=Lamboy|first2=Francisco|last2=Salgado-Robles|chapter=Introduction: Spanish in the United States and across Domains}}</ref> |

|||

According to the 2020 census, over 60 million people of the U.S. population were of [[Hispanic]] or [[Hispanic America]]n by origin.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html|title=Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census|date=12 August 2021|publisher=[[U.S. Census Bureau]]|access-date=23 January 2021|archive-date=15 August 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210815165418/https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html|url-status=live}}</ref> In turn, 41.8 million people in the United States aged five or older speak Spanish at home, or about 13% of the population.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Language%20Spoken%20at%20Home&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1601|title=American Community Survey Explore Census Data|access-date=24 January 2022|archive-date=17 October 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211017182821/https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Language%20Spoken%20at%20Home&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1601|url-status=live}}</ref> Spanish predominates in the unincorporated territory of [[Puerto Rico]], where it is also an official language along with English. |

|||

[[Image:Map-Hispanophone World.png|thumb|right|500px|The Hispanophone world; the dark blue indicates where it is the official language, and the light blue indicates where it is used as a second language.]] |

|||

Spanish is by far the most common second language in the country, with over 50 million total speakers if non-native or second-language speakers are included.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.elpais.com/articulo/cultura/speak/spanish/Espana/elpepucul/20081006elpepicul_1/Tes|title=Más 'speak spanish' que en España|access-date=6 October 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110520111353/http://www.elpais.com/articulo/cultura/speak/spanish/Espana/elpepucul/20081006elpepicul_1/Tes|archive-date=20 May 2011|url-status=live}} (in Spanish)</ref> While English is the de facto national language of the country, Spanish is often used in public services and notices at the federal and state levels. Spanish is also used in administration in the state of [[New Mexico]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Crawford |first1=John |title=Language loyalties: a source book on the official English controversy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wLoJ31HXl40C&pg=PA62 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |year=1992 |page=62 |isbn=9780226120164 |access-date=14 November 2023 |archive-date=30 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231130015012/https://books.google.com/books?id=wLoJ31HXl40C&pg=PA62 |url-status=live}}</ref> The language has a strong influence in major metropolitan areas such as those of [[Greater Los Angeles area|Los Angeles]], [[Miami metropolitan area|Miami]], [[San Antonio metropolitan area|San Antonio]], [[New York metropolitan area|New York]], [[San Francisco Bay Area|San Francisco]], [[Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex|Dallas]], [[Greater Tucson|Tucson]] and [[Phoenix metropolitan area|Phoenix]] of the [[Arizona Sun Corridor]], as well as more recently, [[Chicago metropolitan area|Chicago]], [[Las Vegas Valley|Las Vegas]], [[Greater Boston|Boston]], [[Greater Denver|Denver]], [[Greater Houston|Houston]], [[Greater Indianapolis|Indianapolis]], [[Greater Philadelphia|Philadelphia]], [[Greater Cleveland|Cleveland]], [[Greater Salt Lake City|Salt Lake City]], [[Greater Atlanta|Atlanta]], [[Greater Nashville|Nashville]], [[Greater Orlando|Orlando]], [[Greater Tampa|Tampa]], [[Greater Raleigh|Raleigh]] and [[Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area|Baltimore-Washington, D.C.]] due to 20th- and 21st-century immigration. |

|||

Spanish is one of the official languages of the [[European Union]], the [[Organization of American States]], the [[Organization of Ibero-American States]], the [[United Nations]], and the [[Union of South American Nations]]. |

|||

=== |

====Rest of the Americas==== |

||

Although Spanish has no official recognition in the former [[British overseas territories|British colony]] of [[Belize]] (known until 1973 as [[British Honduras]]) where English is the sole official language, according to the 2022 census, 54% of the total population are able to speak the language.<ref>{{Cite report |url=https://sib.org.bz/wp-content/uploads/Languages_Infographic_2022.pdf|title=Languages spoken in Belize, 2022 Census|date=2022 |language=en |access-date=11 September 2024}}</ref> |

|||

Spanish is an official language of Spain, the country for which it is named and from which it originated. It is also spoken in [[Gibraltar]], though English is the official language.<ref>[https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/gi.html CIA World Factbook — Gibraltar]</ref> Likewise, it is spoken in [[Andorra]] though [[Catalan language|Catalan]] is the official language.<ref name="encartaand">{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761554662/Andorra.html#s3 |

|||

|title=Andorra — People |

|||

|publisher=MSN Encarta |

|||

|accessdate=2007-08-20}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3164.htm |

|||

|title=Background Note: Andorra |

|||

|publisher=U.S. Department of State: Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs |

|||

|month=January |

|||

|year=2007 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-08-20}}</ref> It is also spoken by small communities in other European countries, such as the [[United Kingdom]], [[France]], and [[Germany]].<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/languages/european_languages/languages/spanish.shtml BBC Education — Languages], Languages Across Europe — Spanish.</ref> Spanish is an official language of the [[European Union]]. In Switzerland, Spanish is the [[mother tongue]] of 1.7% of the population, representing the first minority after the 4 official languages of the country.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.all-about-switzerland.info/swiss-population-languages.html |

|||

|title=Switzerland's Four National Languages |

|||

|publisher=all-about-switzerland.info |

|||

|accessdate=2007-09-19}}</ref> |

|||

Due to its proximity to Spanish-speaking countries and small existing [[Trinidadian Spanish|native Spanish speaking]] minority, [[Trinidad and Tobago]] has implemented Spanish language teaching into its education system. The Trinidadian and Tobagonian government launched the ''Spanish as a First Foreign Language'' (SAFFL) initiative in March 2005.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tradeind.gov.tt/SIS/FAQ.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101103080637/http://www.tradeind.gov.tt/SIS/FAQ.htm |archive-date=3 November 2010 |title=FAQ |work=The Secretariat for The Implementation of Spanish |publisher=Government of the Republic |location=Trinidad and Tobago |access-date=10 January 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

===The Americas === |

|||

====Latin America==== |

|||

Most Spanish speakers are in [[Latin America]]; of most countries with the most Spanish speakers, only [[Spain]] is outside of the [[Americas]]. [[Mexico]] has most of the world's native speakers. Nationally, Spanish is the official language of [[Argentina]], [[Bolivia]] (co-official [[Quechua]] and [[Aymara language|Aymara]]), [[Chile]], [[Colombia]], [[Costa Rica]], [[Cuba]], [[Dominican Republic]], [[Ecuador]], [[El Salvador]], [[Guatemala]], [[Honduras]], [[Mexico]] , [[Nicaragua]], [[Panama]], [[Paraguay]] (co-official [[Guarani language|Guaraní]]<ref>[http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=PY Ethnologue - Paraguay(2000)]. Guaraní is also the most-spoken language in Paraguay by its native speakers.</ref>), [[Peru]] (co-official [[Quechua]] and, in some regions, [[Aymara language|Aymara]]), [[Uruguay]], and [[Venezuela]]. Spanish is also the official language (co-official language [[English language|English]]) in the U.S. commonwealth of [[Puerto Rico]].<ref>{{cite news |

|||

|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CE1D8163AF93AA15752C0A965958260&n=Top%2fReference%2fTimes%20Topics%2fSubjects%2fE%2fEnglish%20Language |

|||

|title= Puerto Rico Elevates English |

|||

|date=[[January 29]], [[1993]] |

|||

|publisher=the New York Times |

|||

|accessdate=2007-10-06}}</ref> |

|||

Spanish has historically had a significant presence on the [[Dutch Caribbean]] islands of [[Aruba]], [[Bonaire]] and [[Curaçao]] ([[ABC islands (Leeward Antilles)|ABC Islands]]) throughout the centuries and in present times. The majority of the populations of each island (especially Aruba) speaking Spanish at varying although often high degrees of fluency.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Language and education on Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300471435}}</ref> The local language [[Papiamento|Papiamentu]] (Papiamento on Aruba) is heavily influenced by Venezuelan Spanish. |

|||

Spanish has no official recognition in the former [[British overseas territories|British colony]] of [[Belize]], however, per the 2000 census, Spanish is the language most spoken as a first language, with nearly half the country speaking it as a first language and many others speaking it as a second language. <ref name="Belizecen">{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.cso.gov.bz/publications/MF2000.pdf |

|||

|publisher=Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Budget Management, Belize |

|||

|title=Population Census 2000, Major Findings |

|||

|year=2000 |

|||

|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070621080522/http://www.cso.gov.bz/publications/MF2000.pdf |

|||

|archivedate=2007-06-21 |

|||