Capitalism: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [accepted revision] |

Nihil novi (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Economic system based on private ownership}} |

|||

'''Capitalism''' has been defined in various ways (see [[Definitions of capitalism|definitions of capitalism]]). In common usage it refers to an economic system in which all or most of the [[means of production]] are privately owned and operated for profit, and where investments, production, distribution, income, and prices are determined largely through the operation of a "[[free market]]" rather than by centralized state control (as in a [[command economy]]). All modern Western economies contain some degree of capitalism. Most agree that capitalism replaced [[feudalism]], a system where in principle the state, in the form of a hereditary ruler, owned all of the means of production. Capitalism also contrasts with socialism where the means of production are owned by the state or collectively by the community. |

|||

{{About|an economic system}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Capitalist|other uses|Capitalist (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{Pp-pc|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use American English|date=January 2014}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} |

|||

{{Capitalism sidebar}} |

|||

{{Economics sidebar}} |

|||

{{Economic systems sidebar|expanded=by ideology}} |

|||

{{Liberalism sidebar}} |

|||

{{Neoliberalism sidebar}} |

|||

'''Capitalism''' is an [[economic system]] based on the [[private ownership]] of the [[means of production]] and their operation for [[Profit (economics)|profit]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Zimbalist |last2=Sherman |last3=Brown |first1=Andrew |first2=Howard J. |first3=Stuart |title=Comparing Economic Systems: A Political-Economic Approach |publisher=[[Harcourt College Publishing]] |date=October 1988 |isbn=978-0-15-512403-5 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/comparingeconomi0000zimb_q8i6/page/6 6–7] |quote=Pure capitalism is defined as a system wherein all of the means of production (physical capital) are privately owned and run by the capitalist class for a profit, while most other people are workers who work for a salary or wage (and who do not own the capital or the product). |url=https://archive.org/details/comparingeconomi0000zimb_q8i6/page/6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Rosser |first1=Mariana V. |last2=Rosser |first2=J Barkley |title=Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy |publisher=[[MIT Press]] |date=23 July 2003 |isbn=978-0-262-18234-8 |page=7 |quote=In capitalist economies, land and produced means of production (the capital stock) are owned by private individuals or groups of private individuals organized as firms.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Chris |last=Jenks |title=Core Sociological Dichotomies |quote=Capitalism, as a mode of production, is an economic system of manufacture and exchange which is geared toward the production and sale of commodities within a market for profit, where the manufacture of commodities consists of the use of the formally free labor of workers in exchange for a wage to create commodities in which the manufacturer extracts surplus value from the labor of the workers in terms of the difference between the wages paid to the worker and the value of the commodity produced by him/her to generate that profit. |location=London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi |publisher=[[SAGE Publishing]] |page=383}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Challenge of Global Capitalism : The World Economy in the 21st Century |last=Gilpin |first=Robert |author-link=Robert Gilpin |isbn=978-0-691-18647-4 |oclc=1076397003 |date=2018|publisher=Princeton University Press }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sternberg |first1=Elaine |title=Defining Capitalism |journal=[[Economic Affairs (journal)|Economic Affairs]] |date=2015 |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=380–396 |doi=10.1111/ecaf.12141|s2cid=219373247 | issn = 0265-0665}}</ref> The defining characteristics of capitalism include [[private property]], [[capital accumulation]], [[competitive market]]s, [[price system]]s, recognition of [[Property rights (economics)|property rights]], [[self-interest]], [[economic freedom]], [[work ethic]], [[consumer sovereignty]], [[decentralized decision-making]], [[profit motive]], a [[Financial market infrastructure|financial infrastructure of money and investment]] that makes possible [[credit]] and [[debt]], [[entrepreneurship]], [[commodification]], [[voluntary exchange]], [[wage labor]], production of [[commodities]] and [[Service (economics)|service]]s, and a strong emphasis on [[innovation]] and [[economic growth]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Heilbroner |first1=Robert L. |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2018 |publisher=[[Palgrave Macmillan]] |location=London |isbn=978-1-349-95189-5 |pages=1378–1389 |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_154 |language=en |chapter=Capitalism |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_154}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hodgson |first1=Geoffrey M. |title=Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future |date=2015 |publisher=[[University of Chicago Press]] |location=Chicago |isbn=9780226168142 |url=https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo18523749.html}}</ref><ref name = "harris">{{cite journal |last1=Harris |first1=Neal |last2=Delanty |first2=Gerard |title=What is capitalism? Toward a working definition |journal=[[Social Science Information]] |date=2023 |volume=62 |issue=3 |pages=323–344 |doi=10.1177/05390184231203878 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Berend |first1=Ivan T. |title=Capitalism |journal=[[International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences|International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition)]] |date=2015 |pages=94–98 |doi=10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.62003-2|isbn=978-0-08-097087-5 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Antonio |first1=Robert J. |last2=Bonanno |first2=Alessandro |title=Capitalism |journal=The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization |date=2012 |doi=10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog060|isbn=978-1-4051-8824-1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Beamish |first1=Rob |chapter=Capitalism |title=Core Concepts in Sociology |date=2018 |pages=17–22 |doi=10.1002/9781394260331.ch6|isbn=978-1-119-16861-4 }}</ref> In a [[market economy]], decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or ability to maneuver capital or production ability in [[Capital market|capital]] and [[financial market]]s—whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gregory |first1=Paul |last2=Stuart |first2=Robert |year=2013 |title=The Global Economy and its Economic Systems |publisher=[[South-Western College Publishing]] |page=41 |isbn=978-1-285-05535-0 |quote=Capitalism is characterized by private ownership of the factors of production. Decision making is decentralized and rests with the owners of the factors of production. Their decision making is coordinated by the market, which provides the necessary information. Material incentives are used to motivate participants.}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:AdamSmith.jpg|thumb|left|Adam Smith is typically regarded as the intellectual father of capitalism]] |

|||

Most theories of what has come to be called capitalism developed in the [[18th century]], [[19th century]] and [[20th century]], for instance in the context of the [[industrial revolution]] and [[New imperialism|European imperialism]] (e.g. [[Adam Smith|Smith]], [[David Ricardo|Ricardo]], [[Karl Marx|Marx]]), [[The Great Depression]] (e.g.[[John Maynard Keynes|Keynes]]) and the [[Cold war]] (e.g. [[Friedrich Hayek|Hayek]], [[Milton Friedman|Friedman]]). These theorists characterise capitalism as an economic system where capital is privately owned and economic decisions are determined in a free market --that is, by trades that occur as a result of voluntary agreement between buyers and sellers; where a market mentality and [[Entrepreneur|entrepreneurial]] spirit exists; and where specific, legally enforcable, notions of [[property]] and [[contract]] are instituted. Such theories typically try to explain why capitalist economies are likely to generate more economic growth than those subject to a greater degree of governmental intervention (see [[economics]], [[political economy]], [[laissez-faire]]). Some emphasize the private ownership of capital as being the essence of capitalism, while others emphasize the importance of a [[free market]] as a mechanism for the movement and accumulation of [[capital]]. Some note the growth of a [[International trade|global market]] system. Others focus on the application of the market to human [[labor]]. Others, such as Hayek, note the [[self-organization|self-organizing]] character of economies who are not centrally-planned by government. |

|||

Many of these theories call attention to various [[economics|economic]] practices that became institutionalized in [[Europe]] between the [[16th century|16th]] and [[19th century|19th]] centuries, especially involving the right of individuals and groups of individuals acting as "legal persons" (or [[corporations]]) to buy and sell [[capital]] goods, as well as [[land]], [[labor]], and [[money]] (see [[finance]] and [[credit]]), in a [[free market]] (see [[trade]]), and relying on the state for the enforcement of [[private property]] rights rather than on a system of feudal protection and obligations. |

|||

Economists, historians, political economists, and sociologists have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include ''[[Laissez-faire capitalism|laissez-faire]]'' or [[free-market capitalism]], [[anarcho-capitalism]], [[state capitalism]], and [[welfare capitalism]]. Different [[forms of capitalism]] feature varying degrees of [[free market]]s, [[public ownership]],<ref name="gregorystuart">{{cite book|last1=Gregory |first1=Paul |last2=Stuart |first2=Robert |title=The Global Economy and its Economic Systems |publisher=[[South-Western College Publishing]] |date=2013 |isbn=978-1-285-05535-0 |page=107 |quote=Real-world capitalist systems are mixed, some having higher shares of public ownership than others. The mix changes when privatization or nationalization occurs. Privatization is when property that had been state-owned is transferred to private owners. [[Nationalization]] occurs when privately owned property becomes publicly owned.}}</ref> obstacles to free competition, and state-sanctioned [[social policies]]. The degree of [[Competition (economics)|competition]] in [[Market (economics)|markets]] and the role of [[Economic interventionism|intervention]] and [[Regulatory economics|regulation]], as well as the scope of state ownership, vary across different models of capitalism.<ref name="Modern Economics 1986, p. 54">{{cite book |title=Macmillan Dictionary of Modern Economics |edition=3rd |date=1986 |pages=54}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |last=Bronk |first=Richard |title=Which model of capitalism?|url=http://oecdobserver.org/news/archivestory.php/aid/345/Which_model_of_capitalism_.html |url-status=live |magazine=[[OECD Observer]] |publisher=[[OECD]] |date=Summer 2000 |volume=1999 |issue=221–222 |pages=12–15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180406200423/http://oecdobserver.org/news/archivestory.php/aid/345/Which_model_of_capitalism_.html |archive-date=6 April 2018 |access-date=6 April 2018}}</ref> The extent to which different markets are free and the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most of the existing capitalist economies are [[mixed economies]] that combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases [[economic planning]].<ref name="Stilwell">{{cite book |last=Stilwell |first=Frank |author-link=Frank Stilwell (economist) |title=Political Economy: the Contest of Economic Ideas |edition=1st |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |location=Melbourne, Australia |date=2002}}</ref> |

|||

Debates center on whether capitalism |

|||

* is an actual system, or an ideal |

|||

* has been actualized in particular economies, or if not, then to what degree capitalism exists in those (see ''[[mixed economy]]'') |

|||

* is historically specific (that is, that it emerged at a specific time and place), or a system that has existed in various places at various times |

|||

* is a purely economic system, or a political, social, and cultural system as well |

|||

* is [[Sustainability|sustainable]] or not |

|||

* is rational or not |

|||

* tends to enrich more and more people, or to impoverish more and more people. |

|||

Capitalism in its modern form emerged from [[agrarianism]] in [[England]], as well as [[Mercantilism|mercantilist]] practices by European countries between the 16th and 18th centuries. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th century established [[Capitalist mode of production (Marxist theory)|capitalism as a dominant mode of production]], characterized by [[factory|factory work]], and a complex [[Division of labour|division of labor]]. Through the process of [[globalization]], capitalism spread across the world in the 19th and 20th centuries, especially before World War I and after the end of the Cold War. During the 19th century, capitalism was largely unregulated by the state, but became more regulated in the post–[[World War II]] period through [[Keynesianism]], followed by a return of more unregulated capitalism starting in the 1980s through [[neoliberalism]]. |

|||

Aside from referring to an economic or political system, capitalism may also refer to the condition of owning capital. Likewise, in addition to the term "capitalist" referring to someone who favors capitalism, capitalist also commonly refers to a person who owns and control capital. |

|||

The existence of market economies has been observed under many [[forms of government]] and across a vast array of [[historical periods]], [[geographical location]]s, and cultural contexts. The modern industrial capitalist societies that exist today developed in Western Europe as a result of the Industrial Revolution. The accumulation of capital is the primary mechanism through which capitalist economies promote [[economic growth]]. However, it is a characteristic of such economies that they experience a [[business cycle]] of [[economic growth]] followed by recessions.<ref name = "HP">{{cite journal |last1=Hodrick |first1=R. |last2=Prescott|first2= E. |year=1997 |title=Postwar US business cycles: An empirical investigation |journal=Journal of Money, Credit and Banking|volume=29|issue=1 |pages=1–16|doi=10.2307/2953682 |jstor=2953682 |s2cid=154995815 | url = http://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/research/math/papers/451.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

== Etymology == |

== Etymology == |

||

The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of [[Capital (economics)|capital]], appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and dates to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from ''capital'', which evolved from {{lang|la|capitale}}, a late [[Latin]] word based on {{lang|la|caput}}, meaning "head"—which is also the origin of "[[Personal property|chattel]]" and "[[cattle]]" in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). {{lang|la|Capitale}} emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries to refer to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.<ref name="Braudel-1979">{{cite book |last=Braudel |first=Fernand |author-link=Fernand Braudel |title=The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century |publisher=[[Harper and Row]] |date=1979}}</ref>{{rp|232}}<ref name="OED-93">[[James Murray (lexicographer)|James Augustus Henry Murray]]. "Capital". [https://archive.org/details/oedvol02 A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles]. ''Oxford English Press''. {{abbr|Vol.|Volume}} 2. p. 93.</ref> By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and was often interchanged with other words—wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.<ref name="Braudel-1979" />{{rp|233}} |

|||

The etymology of the word '''capital''' has roots in the trade and ownership of animals. The [[Latin]] root of the word '''capital''' is ''capitalis'', from the [[Proto-Indo-European language|proto-Indo-European]] ''kaput'', which means "head", this being how wealth was measured. The more heads of cattle, the better. The terms ''chattel'' (meaning goods, animals, or slaves) and even ''cattle'' itself also derive from this same origin. |

|||

The ''Hollantse ({{langx|de|holländische}}) Mercurius'' uses "capitalists" in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.<ref name="Braudel-1979" />{{rp|234}} In French, [[Étienne Clavier]] referred to ''capitalistes'' in 1788,<ref>E.g., "L'Angleterre a-t-elle l'heureux privilège de n'avoir ni Agioteurs, ni Banquiers, ni Faiseurs de services, ni Capitalistes ?" in [Étienne Clavier] (1788) ''De la foi publique envers les créanciers de l'état : lettres à M. Linguet sur le n° CXVI de ses annales'' [https://books.google.com/books?id=ESMVAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA19 p. 19] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319071130/http://books.google.com/books?id=ESMVAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA19 |date=19 March 2015 }}</ref> four years before its first recorded English usage by [[Arthur Young (writer)|Arthur Young]] in his work ''Travels in France'' (1792).<ref name="OED-93" /><ref>Arthur Young. [https://archive.org/details/travelsduringye03youngoog ''Travels in France''].</ref> In his ''[[Principles of Political Economy and Taxation]]'' (1817), [[David Ricardo]] referred to "the capitalist" many times.<ref>Ricardo, David. Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. 1821. John Murray Publisher, 3rd edition.</ref> English poet [[Samuel Taylor Coleridge]] used "capitalist" in his work ''Table Talk'' (1823).<ref>Samuel Taylor Coleridge. [https://books.google.com/books?id=ma-4W-XiGkIC Tabel ''The Complete Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200223123202/https://books.google.com/books?id=ma-4W-XiGkIC |date=23 February 2020 }}. p. 267.</ref> [[Pierre-Joseph Proudhon]] used the term in his first work, ''[[What is Property?]]'' (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. [[Benjamin Disraeli]] used the term in his 1845 work ''[[Sybil (novel)|Sybil]]''.<ref name="OED-93" /> [[Alexander Hamilton]] used "capitalist" in his [[Report on Manufactures|Report of Manufactures]] presented to the United States Congress in 1791. |

|||

The lexical connections between animal trade and economics can also be seen in the names of many currencies and words about money: fee (''faihu''), rupee (''rupya''), buck (a deerskin), pecuniary (''pecu''), stock (''livestock''), and peso (''pecu'' or ''pashu'') all derive from animal-trade origins. |

|||

The initial use of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense is attributed to [[Louis Blanc]] in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labor").<ref name="Braudel-1979" />{{rp|237}} [[Karl Marx]] frequently referred to the "[[Capital (Marxism)|capital]]" and to the "capitalist mode of production" in ''[[Capital: Critique of Political Economy|Das Kapital]]'' (1867).<ref>{{cite book |last=Saunders |first=Peter |date=1995 |title=Capitalism |publisher=[[University of Minnesota Press]] |page=1}}</ref><ref name=":0">MEW, 23, & Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Oekonomie. Erster Band-Verlag von Otto Meissner (1867)</ref> Marx did not use the form ''capitalism'' but instead used [[Capital (Marxism)|capital]], ''capitalist'' and ''capitalist mode of production'', which appear frequently.<ref name=":0" /><ref>The use of the word "capitalism" appears in ''Theories of Surplus Value'', volume II. ToSV was edited by Kautsky.</ref> Due to the word being coined by socialist critics of capitalism, economist and historian [[Robert Hessen]] stated that the term "capitalism" itself is a term of disparagement and a misnomer for [[Individualism#Economic individualism|economic individualism]].<ref>Hessen, Robert (2008) "Capitalism", in Henderson, David R. (ed.) ''The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics'' p. 57</ref> [[Bernard Harcourt]] agrees with the statement that the term is a misnomer, adding that it misleadingly suggests that there is such a thing as "[[Capital (economics)|capital]]" that inherently functions in certain ways and is governed by stable economic laws of its own.<ref>Harcourt, Bernard E. (2020) ''For Coöperation and the Abolition of Capital, Or, How to Get Beyond Our Extractive Punitive Society and Achieve a Just Society'', Rochester, NY: Columbia Public Law Research Paper No. 14-672, p. 31</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Thackeray_william.jpg|150px|thumb|right|The first known use of the word "capitalism" was by novelist William Thackeray in 1854]] |

|||

The first use of the word "capitalism" in English is by novelist [[William Makepeace Thackeray|Thackeray]] in [[1854]], by which he meant having ownership of capital. In [[1867]] [[Proudhon]] used the term "capitalist" to refer to owners of capital, and Marx and Engels refer to the "capitalist form of production" ("''kapitalistische Produktionsform''") and in ''[[Das Kapital]]'' to ''"Kapitalist"'', "capitalist" (meaning a private owner of capital). By the early [[20th century]] the term had become widespread, as evidenced by [[Max Weber]]'s use of the term in his ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'' in [[1904]], and [[Werner Sombart]]'s [[1906]] ''Modern Capitalism''. The [[Oxford English Dictionary|OED]] cites the use of the term "private capitalism" by [[Karl Daniel Adolf Douai]], German-American [[socialism|socialist]] and [[abolitionism|abolitionist]] in the late [[19th century]], in an [[1877]] work entitled "Better Times", and a citation by an unknown author in [[1884]] in the pages of [[Pall Mall]] magazine. |

|||

In the [[English language]], the term "capitalism" first appears, according to the ''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'' (OED), in 1854, in the novel ''[[The Newcomes]]'' by novelist [[William Makepeace Thackeray]], where the word meant "having ownership of capital".<ref name="OED-94">[[James Murray (lexicographer)|James Augustus Henry Murray]]. "Capitalism" p. 94.</ref> Also according to the OED, [[Carl Adolph Douai]], a [[German Americans|German American]] [[Socialism|socialist]] and [[Abolitionism in the United States|abolitionist]], used the term "private capitalism" in 1863. |

|||

Under the [[Marxist theory]] of [[ideology]], a dominant economic class is believed to have its own ideology serving its class interests. The ideology of the "capitalist class" or [[bourgeoisie]] -- economic [[liberalism]] -- also came to be known as "capitalism", giving the word another meaning. This usage has been adopted outside of Marxist circles, and today many economic liberals self-describe as "capitalists", even if they are not personally involved in business investment. |

|||

Other terms sometimes used for capitalism are: |

|||

* [[Capitalist mode of production (Marxist theory)|Capitalist mode of production]]<ref>{{cite book |last=Mandel |first=Ernst |author-link=Ernst Mandel |title=An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C&pg=PA24 |year=2002 |publisher=[[Resistance Books]] |isbn=978-1-876646-30-1 |page=24 |access-date=29 January 2017 |archive-date=15 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170215160137/https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C&pg=PA24 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

''Main article: [[History of capitalism (practice)]]'' |

|||

* [[Economic liberalism]]<ref>{{cite journal |title=Adam Smith and His Legacy for Modern Capitalism |last=Werhane |first=P. H. |journal=The Review of Metaphysics |volume=47 |year=1994 |issue=3}}</ref> |

|||

* Free enterprise<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Free enterprise |encyclopedia=Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus |edition=Third |publisher=Philip Lief Group |date=2008}}</ref>{{page needed|date=July 2021}} |

|||

* Free enterprise economy<ref name="britannica" /> |

|||

* [[Free market]]<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise" />{{page needed|date=July 2021}} |

|||

* Free market economy<ref name="britannica" /> |

|||

* ''[[Laissez-faire]]''<ref name=Barrons>{{cite book |title=Barrons Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms |date=1995 |page=74}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Market economy]]<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/market%20economy |title=Market economy |dictionary=Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary}}</ref> |

|||

* Profits system<ref>{{cite book |last=Shutt |first=Harry |title=Beyond the Profits System: Possibilities for the Post-Capitalist Era |publisher=[[Zed Books]] |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-84813-417-1}}</ref>{{page needed|date=July 2021}} |

|||

* Self-regulating market<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise" />{{page needed|date=July 2021}} |

|||

== Definition == |

|||

* [[Emergence of early capitalism]] |

|||

There is no universally agreed upon definition of capitalism; it is unclear whether or not capitalism characterizes an entire society, a specific type of social order, or crucial |

|||

* [[Capitalism in the nineteenth century]] |

|||

components or elements of a society.<ref name="wolf">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Wolf |first=Harald |editor1-last=Ritzer |editor1-first=George|title=Capitalism |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Social Theory|pages=76–80|date=2004 |publisher=Sage Publications|isbn=978-1-4522-6546-9}}</ref> Societies officially founded in opposition to capitalism (such as the [[Soviet Union]]) have sometimes been argued to actually exhibit characteristics of capitalism.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Howard |first1=M.C. |last2=King |first2=J.E. |title='State Capitalism' in the Soviet Union |journal=History of Economics Review |date=January 2001 |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=110–126 |doi=10.1080/10370196.2001.11733360 |s2cid=42809979 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10370196.2001.11733360 |language=en |issn=1037-0196}}</ref> [[Nancy Fraser]] describes usage of the term "capitalism" by many authors as "mainly rhetorical, functioning less as an actual concept than as a gesture toward the |

|||

* [[Capitalism in the twentieth century]] |

|||

need for a concept".<ref name="harris"/> Scholars who are uncritical of capitalism rarely actually use the term "capitalism".<ref name="delacroix">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Delacroix |first=Jacques |editor1-last=Ritzer |editor1-first=George |title=Capitalism |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Social Theory|date=2007 |publisher=Wiley|doi=10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc004 |isbn=978-1-4051-2433-1|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc004}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Capitalism in the twenty-first century]] |

|||

Some doubt that the term "capitalism" possesses valid scientific dignity,<ref name="wolf"/> and it is generally not discussed in [[mainstream economics]],<ref name="harris"/> with economist [[Daron Acemoglu]] suggesting that the term "capitalism" should be abandoned entirely.<ref>{{cite book |last=Acemoglu |first=Daron |date=2017 |editor1-last=Frey |editor1-first=Bruno S.|editor2-last = Iselin|editor2-first = David |title=Economic Ideas You Should Forget |publisher=Springer|pages=1–3 |chapter=Capitalism|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_1 |isbn=978-3-319-47457-1|chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_1}}</ref> Consequently, understanding of the concept of capitalism tends to be heavily influenced by opponents of capitalism and by the followers and critics of Karl Marx.<ref name="delacroix"/> |

|||

==History |

== History == |

||

{{Main|History of capitalism}} |

|||

[[File:Jacopo Pontormo 055.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|[[Cosimo de' Medici]] (pictured in a 16th-century portrait by [[Pontormo]]) built an international financial empire and was one of the first [[Medici bank]]ers.]] |

|||

[[File:Augsburg - Markt.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|[[Augsburg]], the centre of early capitalism<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Behringer |first1=Wolfgang |contribution=Core and Periphery: The Holy Roman Empire as a Communication(s) Universe |title=The Holy Roman Empire, 1495–1806 |date=2011 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-960297-1 |pages=347–358|url=https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00004689/behringer_core.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00004689/behringer_core.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |access-date=7 August 2022}}</ref>]] |

|||

Capitalism, in its modern form, can be traced to the emergence of agrarian capitalism and mercantilism in the early [[Renaissance]], in city-states like [[Florence]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.economist.com/node/13484709 |title=Cradle of capitalism |newspaper=[[The Economist]] |date=16 April 2009 |access-date=9 March 2015 |archive-date=18 January 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180118055643/http://www.economist.com/node/13484709 |url-status=live}}</ref> [[Capital (economics)|Capital]] has existed incipiently on a small scale for centuries<ref name="WarburtonDavid">{{cite book |last=Warburton |first=David |title=Macroeconomics from the beginning: The General Theory, Ancient Markets, and the Rate of Interest |location=Paris |publisher=Recherches et Publications |date=2003 |pages=49}}</ref> in the form of merchant, renting and lending activities and occasionally as small-scale industry with some wage labor. Simple [[commodity]] exchange and consequently simple commodity production, which is the initial basis for the growth of capital from trade, have a very long history. During the [[Islamic Golden Age]], [[Arabs]] promulgated capitalist economic policies such as free trade and banking. Their use of [[Indo-Arabic numerals]] facilitated [[bookkeeping]]. These innovations migrated to Europe through trade partners in cities such as Venice and Pisa. Italian [[mathematicians]] traveled the Mediterranean talking to Arab traders and returned to popularize the use of Indo-Arabic numerals in Europe.<ref name="Koehler, Benedikt">{{cite book |last=Koehler |first=Benedikt |title=Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism |quote=In Baghdad, by the early tenth century a fully-fledged banking sector had come into being... |pages=2 |publisher=[[Lexington Books]] |date=2014}}</ref> |

|||

The conception of what constitutes capitalism has changed significantly over time, as well as varying depending on the political perspective and analytical approach taken. [[Adam Smith]] focused on the role of enlightened self-interest (the "invisible hand") and the role of [[specialisation]] in making capital accumulation efficient. Some proponents of capitalism (like [[Milton Friedman]], [[Ayn Rand]] and [[Alan Greenspan]]) emphasize the role of [[free market]]s, which they claim promote [[cooperation]] between individuals, innovation, economic growth, as well as [[liberty]]. For many (like [[Immanuel Wallerstein]]), capitalism hinges on the elaboration of an economic system in which [[good (economics)|goods]] and [[service]]s are traded in [[market]]s, and [[capital good]]s belong to non-state entities, onto a global scale. For others (like [[Karl Marx]]), it is defined by the creation of a [[labor market]] in which most people have to sell their [[labor-power]] in order to survive. As Marx argued (see also [[Hilaire Belloc]]), capitalism is also distinguished from other market economies with private ownership by the concentration of the means of production in the hands of individuals. Many others use capitalism as a synonym for a [[market economy]]. |

|||

=== Agrarianism === |

|||

== Characteristics of capitalist economies == |

|||

The economic foundations of the feudal agricultural system began to shift substantially in 16th-century England as the [[manorial system]] had broken down and land began to become concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. Instead of a [[serf]]-based system of labor, workers were increasingly employed as part of a broader and expanding money-based economy. The system put pressure on both landlords and tenants to increase the productivity of agriculture to make profit; the weakened coercive power of the [[aristocracy]] to extract peasant [[Excess supply|surpluses]] encouraged them to try better methods, and the tenants also had incentive to improve their methods in order to flourish in a competitive [[labor economics|labor market]]. Terms of rent for land were becoming subject to economic market forces rather than to the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Brenner |first1=Robert |title=The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism |journal=[[Past & Present (journal)|Past & Present]] |date=1 January 1982 |issue=97 |pages=16–113 |doi=10.1093/past/97.1.16 |jstor=650630}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://monthlyreview.org/1998/07/01/the-agrarian-origins-of-capitalism |title=The Agrarian Origins of Capitalism |access-date=17 December 2012 |date=July 1998 |archive-date=11 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191211183143/https://monthlyreview.org/1998/07/01/the-agrarian-origins-of-capitalism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

A set of broad characteristics are generally agreed on by both advocates and critics of capitalism. These are a [[private sector]], [[private property]], free enterprise, [[profit]], [[economic growth]], [[economic mobility]], unequal distribution of [[wealth]], competition, evolving [[entrepreneurial]] networks and social arrangements, and the existence of [[free markets]] (including the [[labor market]]). |

|||

=== |

=== Mercantilism === |

||

{{Main|Mercantilism}} |

|||

[[Image:Urbine221dc.jpg|thumb|right|150px]] |

|||

[[File:Lorrain.seaport.jpg|left|thumb|A painting of a French seaport from 1638 at the height of [[mercantilism]]]] |

|||

[[Image:Egger.JPG|thumb|right|150px|Egger Chipboard Factory in Northumberland, England]] |

|||

[[File:Lord Clive meeting with Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey.jpg|left|thumb|[[Robert Clive]] with the [[Nawabs of Bengal]] after the [[Battle of Plassey]] which began the British rule in [[Bengal Presidency|Bengal]]]] |

|||

[[Image:Dairycattle2173.JPG|thumb|right|150px|Private ownership of most of the means of production, such land, power production, and manufacturing, is an essential characteristic of capitalism.]] |

|||

The economic doctrine prevailing from the 16th to the 18th centuries is commonly called [[mercantilism]].<ref name=GSGB>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C |title=An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory |date= 2002 |publisher=[[Resistance Books]] |via=[[Google Books]] |isbn=978-1-876646-30-1 |access-date=27 August 2016 |archive-date=11 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161211173733/https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Burnham">{{cite book |last=Burnham |first=Peter |author-link=Peter Burnham |title=Capitalism: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |year=2003}}</ref> This period, the [[Age of Discovery]], was associated with the geographic exploration of foreign lands by merchant traders, especially from England and the [[Low Countries]]. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist methods.<ref name="Scott" /> Most scholars consider the era of merchant capitalism and mercantilism as the origin of modern capitalism,<ref name="Burnham"/><ref name="Encyclopædia Britannica 2006">''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (2006)</ref> although [[Karl Polanyi]] argued that the hallmark of capitalism is the establishment of generalized markets for what he called the "fictitious commodities", i.e. land, labor and money. Accordingly, he argued that "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date".<ref>{{cite book |last=Polanyi |first=Karl |author-link=Karl Polanyi |title=The Great Transformation |publisher=[[Beacon Press]] |location=Boston |date=1944 |pages=87}}</ref> |

|||

An essential characteristic of capitalism is the institution of rule of law in establishing and protecting private property, including, most notably, private ownership of the [[means of production]]. Private property was embraced in some earlier systems legal systems such as in ancient Rome [http://www.libertystory.net/LSBIGSTORIESROMANPROPERTYLAW.htm], but protection of these rights was sometimes difficult, especially since Rome had no police [http://nefer-seba.net/essays/roman-police.php]. Such and other earlier system often forced the weak had to accept the leadership of a strong patron or lord and pay him for protection. It has been argued that a strong formal property and legal system made possible a) greater independence; b) clear and provable protected ownership; c) the standardization and integration of property rules and property information in the country as a whole; d) increased trust arising from a greater certainty of punishment for cheating in economic transactions; e) more formal and complex written statements of ownership that permitted the easier assumption of shared risk and ownership in companies, and the insurance of risk; f) greater availability of loans for new projects, since more things could be used as collateral for the loans; g) easier and more reliable information regarding such things as credit history and the worth of assets; h) an increased fungibility, standardization and transferability of statements documenting the ownership of property, which paved the way for structures such as national markets for companies and the easy transportation of property through complex networks of individuals and other entities. All of these things enhanced economic growth. |

|||

England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the [[Elizabethan Era]] (1558–1603). A systematic and coherent explanation of balance of trade was made public through [[Thomas Mun]]'s argument ''England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure.'' It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.<ref>{{cite book |first1=David |last1=Onnekink |first2=Gijs |last2=Rommelse |title=Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M1QdbzdTimsC&pg=PA257 |year=2011 |publisher=[[Ashgate Publishing]] |page=257 |isbn=978-1-4094-1914-3 |access-date=27 June 2015 |archive-date=19 March 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319130220/http://books.google.com/books?id=M1QdbzdTimsC&pg=PA257 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Capitalism is often contrasted to [[socialism]] in that besides embracing private property in terms of personal possessions, it supports private ownership of the means of production (compare [[definitions of socialism]]). Those who support capitalism often credit the lack of control over the means of production by government as crucial to maximizing economic output. [[Ludwig von Mises]], in ''Liberalism'', says that the "history of private ownership of the means of production coincides with the history of the development of mankind from an animal-like condition to the highest reaches of modern civilization." [http://www.mises.org/liberal/ch2sec1.asp] [[Karl Marx]] and Marxists, on the other hand, hold that private ownership of the means of production is the source of social ills and advocate its abolition. In all modern economies some of the means of production are owned by the state, however an economy is not considered capitalism unless the bulk of ownership is private. Some characterize those that have a mixture of state and private ownership as "[[mixed economy|mixed economies]]." |

|||

European [[merchant]]s, backed by state controls, subsidies and [[monopoly|monopolies]], made most of their profits by buying and selling goods. In the words of [[Francis Bacon]], the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices...".<ref>Quoted in {{cite book |first=George |last=Clark |title=The Seventeenth Century |location=New York |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |date=1961 |page=24}}</ref> |

|||

Many governments extend the concept of private property to ideas, in the form of "[[intellectual property]]." It has been argued that the introduction of the [[patent]] system was a crucial factor behind the rapid development and widespread use of new technology and [[memes]] during and following the industrial revolution. [http://depts.washington.edu/~teclass/mit/khanSokoloff.pdf]. Some oppose the establishment of intellectual property as being counterproductive or coercive. Others argue that some intellectual property rights may be too rigid or constraining to innovation, favoring weaker protections. |

|||

After the period of the [[proto-industrialization]], the [[British East India Company]] and the [[Dutch East India Company]], after massive contributions from the [[Mughal Bengal]],<ref name="Prakash">[[Om Prakash (historian)|Om Prakash]], "[http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3447600139/WHIC?u=seat24826&xid=6b597320 Empire, Mughal]", ''History of World Trade Since 1450'', edited by [[John J. McCusker]], vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, ''World History in Context''. Retrieved 3 August 2017</ref><ref name="ray">{{cite book |first=Indrajit |last=Ray |year=2011 |title=Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CHOrAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |pages=57, 90, 174 |isbn=978-1-136-82552-1 |access-date=20 June 2019 |archive-date=29 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160529021839/https://books.google.com/books?id=CHOrAgAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> inaugurated an expansive era of commerce and trade.<ref name=Banaji>{{cite journal |last=Banaji |first=Jairus |year=2007 |title=Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism |journal=[[Journal Historical Materialism]] |volume=15 |pages=47–74 |doi=10.1163/156920607X171591 |url=http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15983/1/Islam%20and%20capitalism.pdf |access-date=20 April 2018 |archive-date=29 March 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180329015002/http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15983/1/Islam%20and%20capitalism.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="britannica2">{{cite book |title=Economic system:: Market systems |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178493/economic-system/61117/Market-systems#toc242146 |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |year=2006 |access-date=4 January 2009 |archive-date=24 May 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090524075921/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178493/economic-system/61117/Market-systems#toc242146 |url-status=live}}</ref> These companies were characterized by their [[colonialism|colonial]] and [[Expansionism|expansionary]] powers given to them by nation-states.<ref name="Banaji" /> During this era, merchants, who had traded under the previous stage of mercantilism, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a [[return on investment]]. |

|||

=== Free market === |

|||

The idealized notion of a "[[free market]]" where all economic decisions regarding transfers of money, good, and services take place on a voluntary basis, free of coercive influence, is commonly considered to be an essential characteristic of capitalism. Rather than these economic decisions being decreed by government they are determined in a decentralized manner by individuals trading, bargaining, cooperating, and competing with each other. In a free market, government may act in a defensive mode to forbid coercion among market participants but does not engage in proactive interventionist coercion. |

|||

=== Industrial Revolution === |

|||

A legal system that grants and protects property rights provides property owners the liberty to sell their property in accordance to their own valuation of that property; if there are no willing buyers at their offered price they have the freedom to retain it. According to standard capitalist theory, as explained by Adam Smith in Wealth of Nations, when individuals make a trade they value what they are purchasing more than they value what they are giving in exchange for a commodity. If this were not the case, then they would not make the trade but retain ownership of the more valuable commodity. This notion underlies the concept of mutually-beneficial trade where it is held that both sides tend to benefit by an exchange. |

|||

{{Main|Industrial Revolution}} |

|||

[[File:Maquina vapor Watt ETSIIM.jpg|thumb|The [[Watt steam engine]], fuelled primarily by [[coal]], propelled the [[Industrial Revolution]] in [[United Kingdom|Britain]].<ref>Watt steam engine image located in the lobby of the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the [[Technical University of Madrid|UPM]]{{clarify|date=April 2016}} ([[Madrid]]).</ref>]] |

|||

In the mid-18th century a group of economic theorists, led by [[David Hume]] (1711–1776)<ref>{{cite book |last=Hume |first=David |author-link=David Hume |title=Political Discourses |url=https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-125702-2590 |location=Edinburgh |publisher=A. Kincaid & A. Donaldson |year=1752}}</ref> and [[Adam Smith]] (1723–1790), challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines—such as the belief that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state. |

|||

During the [[Industrial Revolution]], [[industrialists]] replaced merchants as a dominant factor in the capitalist system and effected the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of [[artisan]]s, guilds and [[journeyman|journeymen]]. Industrial capitalism marked the development of the [[factory system]] of manufacturing, characterized by a complex [[division of labor]] between and within work process and the routine of work tasks; and eventually established the domination of the [[Capitalist mode of production (Marxist theory)|capitalist mode of production]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burnham |first1=Peter |author1-link=Peter Burnham |year=1996 |chapter=Capitalism |editor1-last=McLean |editor1-first=Iain |editor2-last=McMillan |editor2-first=Alistair |title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |series=Oxford Quick Reference |edition=3 |location=Oxford |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |publication-date=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-101827-5 |access-date=14 September 2019 |quote=Industrial capitalism, which Marx dates from the last third of the eighteenth century, finally establishes the domination of the capitalist mode of production. |archive-date=27 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727163404/https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

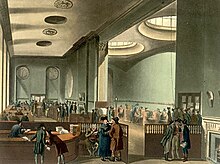

[[Image:CME.JPG|200px|thumb|left|The [[Chicago Mercantile Exchange]]. A free market consists of voluntary trade, free of interventionist regulation. Prices are determined by trade rather than by government.]] |

|||

In regard to pricing of goods and services in a free market, rather than this being ordained by government it is determined by trades that occur as a result of price agreement between buyers and sellers. The prices buyers are willing to pay for a commodity and the prices at which sellers are willing to part with that commodity are directly influenced by [[supply and demand]] (as well as the quantity to be traded). In abstract terms, the price is thus defined as the equilibrium point of the demand and the supply curves, which represent the prices at which buyers would buy (and sellers sell) certain quantities of the good in question. A price above the equilibrium point will lead to oversupply (the buyers which to buy less goods at that price than the sellers are willing to produce), while a price below the equilibrium will lead to the opposite situation. When the price a buyer is willing to pay coincides with the price a seller is willing to offer, a trade occurs and price is determined. |

|||

Industrial Britain eventually abandoned the [[protectionist]] policy formerly prescribed by mercantilism. In the 19th century, [[Richard Cobden]] (1804–1865) and [[John Bright]] (1811–1889), who based their beliefs on the [[Manchester capitalism|Manchester School]], initiated a movement to lower [[tariffs]].<ref name="laissezf">{{cite web |title=Laissez-faire |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081202050426/http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html |archive-date=2 December 2008}}</ref> In the 1840s Britain adopted a less protectionist policy, with the 1846 repeal of the [[Corn Laws]] and the 1849 repeal of the [[Navigation Acts]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burnham |first1=Peter |author1-link=Peter Burnham |year=1996 |chapter=Capitalism |editor1-last=McLean |editor1-first=Iain |editor2-last=McMillan |editor2-first=Alistair |title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |series=Oxford Quick Reference |edition=3 |location=Oxford |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |publication-date=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-101827-5 |access-date=14 September 2019 |quote=For most analysts, mid- to late-nineteenth century Britain is seen as the apotheosis of the laissez-faire phase of capitalism. This phase took off in Britain in the 1840s with the repeal of the Corn Laws, and the Navigation Acts, and the passing of the Banking Act. |archive-date=27 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727163404/https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> Britain reduced tariffs and [[import quota|quotas]], in line with David Ricardo's advocacy of [[free trade]]. |

|||

However, not everyone believes that a free or even a relatively-free market is a good thing. One reason proffered by many to justify economic intervention by government into what would otherwise be a free market is [[market failure]]. A [[market failure]] is a case in which a market fails to "efficiently" provide or allocate goods and services (for example, a failure to allocate goods in way some see as socially or morally preferable). Some believe that the lack of "perfect information" or "perfect competition" in a free market is grounds for government intervention (see ''[[perfect competition]]''). Other situations or activities often perceived as problems with a free market may appear, such [[monopoly|monopolies]], [[monopsony|monopsonies]], information inequalities (e.g. [[insider trading]]), or [[price gouging]]. Wages determined by a free market mechanism are also commonly seen as a problem by those who would claim that some wages are unjustifiably low or unjustifiably high. Another critique is that free markets usually fail to deal with the problem of [[externality|externalities]], where an action by an agent positively or negatively affects another agent without any compensation taking place. The most widely known externality is [[pollution]]. More generally, the free market allocation of resources in areas such as health care, unemployment, wealth inequality, and education are considered market failures by some. Also, governments overseeing economies typically labeled as capitalist have been known to set mandatory ''[[price floor|price floors]]'' or ''[[price ceiling|price ceilings]]'' at times, thereby interfering with the free market mechanism. This usually occurred either in times of crises, or was related to goods and services which were viewed as strategically important. [[Electricity]], for example, is a good that was or is subject to price ceilings in many countries. Many eminent economists have analysed market failures, and see governments as having a legitimate role as mitigators of these failures, for examples through regulation and compensation schemes. |

|||

=== Modernity === |

|||

However, supporters of less state interference, such as libertarian economist [[Milton Friedman]] and Austrian School economists, oppose all or some of such interventions. They argue that only what they see as coercive activities should be regulated and that regulations that go beyond protecting free markets actually ''restrict'' competition and reduce efficiency of those markets. [[Libertarians]], for example, tend to regard pollution as violation of individual rights when it intrudes on the person or property of individuals and therefore advocate regulatory mechanisms. Laissez-faire advocates tend to maintain that the notion of "market failure" is a misguided contrivance used to justify coercive government action for anything from furthering egalitarian social goals to unfairly benefitting poorly-performing business competitors. They do not oppose monopolies unless they maintain their existence through coercion to prevent competition (see ''[[coercive monopoly]]''), and often assert that monopolies have historically only developed ''because'' of government intervention rather than due to a lack of intervention. They may argue that minimum wage laws create unemployment or that law against insider trading inhibit market efficiency and transparency. While economists tend to offer pragmatic arguments, some individuals put forth moral justifications for completely free markets. |

|||

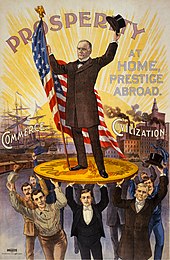

[[File:McKinley Prosperity.jpg|thumb|upright|The [[gold standard]] formed the financial basis of the international economy from 1870 to 1914.]] |

|||

Broader processes of [[globalization]] carried capitalism across the world. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, a series of loosely connected market systems had come together as a relatively integrated global system, in turn intensifying processes of economic and other globalization.<ref name="SAGE Publications">{{cite book |year=2007 |last1=James |first1=Paul |author-link=Paul James (academic) |last2=Gills |first2=Barry |title=Globalization and Economy, Vol. 1: Global Markets and Capitalism |url=https://www.academia.edu/4199690 |publisher=[[SAGE Publications]] |location=London |page=xxxiii}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Impact of Global Capitalism on the Environment of Developing Economies |url=http://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/93716/1/04_Osariyekemwen%20Igiebor.pdf |journal=Impact of Global Capitalism on the Environment of Developing Economies: The Case of Nigeria |pages=84 |access-date=31 July 2020 |archive-date=20 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200320071239/http://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/93716/1/04_Osariyekemwen%20Igiebor.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> Late in the 20th century, capitalism overcame a challenge by [[Planned economy|centrally-planned economies]] and is now the encompassing system worldwide,<ref name="britannica">{{cite book |title=Capitalism |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/93927/capitalism |date=10 November 2014 |access-date=24 March 2015 |archive-date=29 June 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629021539/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/93927/capitalism |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=James |first=Fulcher |title=Capitalism, A Very Short Introduction |quote=In one respect there can, however, be little doubt that capitalism has gone global and that is in the elimination of alternative systems |pages=99 |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |date=2004 |isbn=978-0-19-280218-7}}</ref> with the [[mixed economy]] as its dominant form in the industrialized Western world. |

|||

Some dismiss the whole idea of "free markets", claiming that they are exploitative or coercive in essence. For example, some say that wages set by a free market rather than by government decree is exploitative since capitalists have appropriated private ownership of resources, thereby putting individuals in a position to accept low wages in order to survive. |

|||

[[Industrialization]] allowed cheap production of household items using [[economies of scale]], while rapid [[population growth]] created sustained demand for commodities. The [[imperialism]] of the 18th-century decisively shaped globalization.<ref name="SAGE Publications" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=Martin |last2=Thompson |first2=Andrew |date=1 January 2014 |title=Empire and Globalisation: from 'High Imperialism' to Decolonisation |journal=The International History Review |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=142–170 |doi=10.1080/07075332.2013.828643 |s2cid=153987517 |issn=0707-5332|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Globalization and Empire |url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/47230635.pdf |journal=Globalization and Empire |access-date=31 July 2020 |archive-date=23 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200923063531/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/47230635.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Europe and the causes of globalization |url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/7045619.pdf |journal=Europe and the Causes of Globalization, 1790 to 2000 |access-date=31 July 2020 |archive-date=7 December 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171207091124/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/7045619.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

[[Financial markets]], though some of these markets are far from being free due to heavy regulation, allow the large scale, standardized, and easy trading of [[debt]], [[foreign exchange]], and ownership of companies. Similar changes have taken place for products from [[agriculture]], [[mining]], and [[energy]] production. Standardized markets have even appeared for [[pollution]] rights and for the prediction of future events like future [[weather]] and political elections. |

|||

After the [[First Opium War|First]] and [[Second Opium War]]s (1839–60) by [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland|Britain]] and [[France]] and the completion of the [[British people|British]] conquest of India by 1858 and the [[French people|French]] conquest of [[Africa]], [[Polynesia]] and [[Indochina]] by 1887, vast populations of Asia became consumers of European exports. Europeans colonized areas of Africa and the Pacific islands. Colonisation by Europeans, notably of Africa by the British and French, yielded valuable natural resources such as [[rubber]], [[diamonds]] and [[coal]] and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies and the United States: |

|||

Markets have, of course, existed throughout human history. Hunter-gatherers used to exchange their goods in [[barter]]. The appearance of money in [[Antiquity]] facilitated exchanges, permitting the flowering of trade fairs in the [[Middle Ages]]. Nevertheless, many regulations existed, and the influence of the [[guild]]s prevented truly free markets. In modern economies, governments likewise do not allow unfettered market operation in many areas, but the price restrictions are much smaller than those imposed by guilds. |

|||

{{blockquote|The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/tr_show01.html |title=Commanding Heights: Episode One: The Battle of Ideas |publisher=[[PBS]] |date=24 October 1929 |access-date=31 July 2010 |archive-date=30 March 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100330093746/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/tr_show01.html |url-status=live}}</ref>}} |

|||

===Profit=== |

|||

[[Image:Profit&Loss.jpeg|200px|thumb|The pursuit of profit is one characteristic of capitalism]] |

|||

The pursuit and realization of [[profit]] is an essential characteristic of capitalism. Profit is derived by selling a product for more than the cost required to produce or acquire it. Some consider the pursuit of profit to be the essence of capitalism. Sociologist and economist, Max Webber, says that "capitalism is identical with the pursuit of profit, and forever renewed profit, by means of conscious, rational, capitalistic enterprise." However, it is not an unique characteristic for capitalism, some hunter-gatherers practiced profitable barter and monetary profit has been known since antiquity. Opponents of capitalism often protest that private owners of capital do not remunerate laborers the full value of their production but keep a portion as profit, claiming this to be exploitative. |

|||

From the 1870s to the early 1920s, the global financial system was mainly tied to the [[gold standard]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Eichengreen|first=Barry|author-link=Barry Eichengreen|date=6 August 2019|title=Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System|edition=3rd|publisher=[[Princeton University Press]]|doi=10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg|isbn=978-0-691-19458-5|s2cid=240840930 |lccn=2019018286}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Eichengreen|first1=Barry|author-link=Barry Eichengreen|last2=Esteves|first2=Rui Pedro|date=2021|editor1-last=Fukao|editor1-first=Kyoji|editor2-last=Broadberry|editor2-first=Stephen|editor2-link=Stephen Broadberry|section=International Finance|title=The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World|publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]]|volume=2: ''1870 to the Present''|pages=501–525|isbn=978-1-107-15948-8}}</ref> The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow were [[United Province of Canada|Canada]] in 1853, [[History of Newfoundland and Labrador|Newfoundland]] in 1865, the United States and Germany (''[[de jure]]'') in 1873. New technologies, such as the [[telegraph]], the [[transatlantic telegraph cable|transatlantic cable]], the [[radiotelephone]], the [[steamship]] and [[railway]]s allowed goods and information to move around the world to an unprecedented degree.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nber.org/papers/w7195 |last1=Bordo |first1=Michael D. |author1-link=Michael D. Bordo |last2=Eichengreen |first2=Barry |author2-link=Barry Eichengreen |last3=Irwin |first3=Douglas A. |title=Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hundred Years Ago? |series=NBER |number=Working Paper No. 7195 |date=June 1999|doi=10.3386/w7195 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Free enterprise === |

|||

In capitalist economies, a predominant proportion of productive capacity has belonged to [[companies]], in the sense of for-profit organisations. This include many forms of organizations that existed in earlier economic systems, such as [[sole proprietorship]]s and [[partnerships]]. Non-profit organizations existing in capitalism include [[cooperative]]s, [[credit unions]] and [[communes]]. |

|||

In the United States, the term "capitalist" primarily referred to powerful businessmen<ref>{{Cite book |last=Andrews |first=Thomas G. |title=Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-674-03101-2 |location=Cambridge |page=64 |author-link=Thomas G. Andrews (historian)}}</ref> until the 1920s due to widespread societal skepticism and criticism of capitalism and its most ardent supporters. |

|||

More unique to capitalism is the form of organization called [[corporation]], which can be both for-profit and non-profit. This entity can act as a virtual person in many matters before the law. This gives some unique advantages to the owners, such as [[limited liability]] of the owners and perpetual lifetime beyond that of current owners. |

|||

[[File:NY stock exchange traders floor LC-U9-10548-6.jpg|thumb|left|The New York [[stock exchange]] [[trading room|traders' floor]] (1963)]] |

|||

A special form of corporation is a corporation owned by [[shareholders]] who can sell their [[shares]] in a market. One can view shares as converting company ownership into a commodity - the ownership rights are divided into units (the shares) for ease of trading in them. Such share trading first took place widely in Europe during the 17th century and continued to develop and spread thereafter. When company ownership is spread among many shareholders, the shareholders generally have votes in the exercise of authority over the company in proportion to the size of their share of ownership. |

|||

Contemporary capitalist societies developed in the West from 1950 to the present and this type of system continues throughout the world—relevant examples started in the [[United States in the 1950s|United States after the 1950s]], [[Trente Glorieuses|France after the 1960s]], [[Spanish miracle|Spain after the 1970s]], [[Economy of Poland|Poland after 2015]], and others. At this stage most capitalist markets are considered{{by whom|date=July 2021}} developed and characterized by developed private and public markets for equity and debt, a high [[standard of living]] (as characterized by the [[World Bank]] and the [[International Monetary Fund|IMF]]), large institutional investors and a well-funded [[banking system]]. A significant [[managerial class]] has emerged{{when|date=July 2021}} and decides on a significant proportion of investments and other decisions. A different future than that envisioned by Marx has started to emerge—explored and described by [[Anthony Crosland]] in the United Kingdom in his 1956 book ''[[The Future of Socialism]]''<ref>{{cite book |last=Crosland |first=Anthony |title=The Future of Socialism |publisher=Jonathan Cape |year=1956 |location=United Kingdom}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> and by [[John Kenneth Galbraith]] in North America in his 1958 book ''[[The Affluent Society]]'',<ref>{{cite book |last=Galbraith |first=John Kenneth |title=The Affluent Society |publisher=[[Houghton Mifflin]] |year=1958 |location=United States}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> 90 years after Marx's research on the state of capitalism in 1867.<ref>{{cite book |last=Shiller |first=Robert |title=Finance and The Good Society |publisher=[[Princeton University Press]] |year=2012 |location=United States}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> |

|||

To a large degree, authority over productive capacity in capitalism has resided with the owners of companies. Within legal limits and the financial means available to them, the owners of each company can decide how it will operate. In larger companies, authority is usually delegated in a hierarchical or [[bureaucracy| bureaucratic]] system of [[management]]. |

|||

The [[Post–World War II economic expansion|postwar boom]] ended in the late 1960s and early 1970s and the economic situation grew worse with the rise of [[stagflation]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Barnes |first=Trevor J. |title=Reading economic geography |publisher=[[Blackwell Publishing]] |isbn=978-0-631-23554-5 |page=127 |year=2004}}</ref> [[Monetarism]], a modification of [[Keynesian economics|Keynesianism]] that is more compatible with ''laissez-faire'' analyses, gained increasing prominence in the capitalist world, especially under the years in office of [[Ronald Reagan]] in the United States (1981–1989) and of [[Margaret Thatcher]] in the United Kingdom (1979–1990). Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called [[Collectivism and individualism|collectivist]] concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual [[choice]], called "remarketized capitalism".<ref name="Fulcher, James 2004">{{cite book |last=Fulcher |first=James |title=Capitalism |edition=1st |location=New York |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |date=2004}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Rotterdam 16.03.05 fortis.jpg|200px|thumb|left|A bank in [[Rotterdam]]: Banks act as merchants of money and suppliers of capital in capitalist economies.]] |

|||

The end of the [[Cold War]] and the [[dissolution of the Soviet Union]] allowed for capitalism to become a truly global system in a way not seen since before [[World War I]]. The development of the [[neoliberal]] global economy would have been impossible without the fall of [[communism]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Gerstle |first=Gary |author-link=Gary Gerstle |date=2022 |title=The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era |url=https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-neoliberal-order-9780197519646?cc=us&lang=en& |location= |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |pages=10–12 |isbn=978-0-19-751964-6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Bartel |first=Fritz |date=2022 |title=The Triumph of Broken Promises: The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism |url=https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=978-0-674-97678-8 |location= |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |pages=5–6, 19 |isbn=978-0-674-97678-8}}</ref> |

|||

Importantly, the owners receive some of the profits or proceeds generated by the company, sometimes in the form of [[dividends]], sometimes from selling their ownership at higher price than their initial cost. They may also re-invest the profit in the company which may increase future profits and value of the company. They may also liquidate the company, selling all of the equipment, land, and other assets, and split the proceeds between them. The price at which ownership of productive capacity sells is generally the maximum of either the [[net present value]] of the expected future stream of profits or the value of the assets, net of any obligations. There is therefore a financial incentive for owners to exercise their authority in ways that increase the productive capacity of what they own. Various owners are motivated to various degrees by this incentive -- some give away a proportion of what they own, others seem very driven to increase their holdings. Nevertheless the incentive is always there, and it is credited by many as being a key aspect behind the remarkably consistent growth exhibited by capitalist economies. Meanwhile, some critics of capitalism claim that the incentive for the owners is exaggerated and that it results in the owners receiving money that rightfully belongs to the workers, while others point to the fact that the incentive only motivates owners to make a profit - something which may not necessarily result in a positive impact on society. Others note that in order to get a profit in a non-violent way, one must satisfy some need among other persons that they are willing to pay for. Also, most people in practice prefer to work for and buy products from for-profit organizations rather than to buy from or work for non-profit and communal production organizations which are legal in capitalist economies and which anyone can start or join. |

|||

Harvard Kennedy School economist Dani Rodrik distinguishes between three historical variants of capitalism:<ref>{{citation |last=Rodrik |first=Dani |title=Capitalism 3.0 |date=2009 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46mtqx.23 |work=Aftershocks |volume= |pages=185–193 |editor-last=Hemerijck |editor-first=Anton |publisher=[[Amsterdam University Press]] |jstor=j.ctt46mtqx.23 |isbn=978-90-8964-192-2 |access-date=14 January 2021 |editor2-last=Knapen |editor2-first=Ben |editor3-last=van Doorne |editor3-first=Ellen}}</ref> |

|||

When starting a [[business]], the initial owners or investors typically provide some money (the [[Capital (economics)|capital]]) which is used by the business to buy or [[lease]] some means of production. For example, the enterprise may buy or [[lease]] a piece of land and a building; it may buy machinery and hire workers ([[Labour (economics)|labor-power]]), or the capitalist may provide the labor himself. The commodities produced by the workers become the property of the capitalist ("capitalist" in this context refers to a person who has capital, rather than a person who favors capitalism), and are sold by the workers on behalf of the capitalist or by the capitalist himself. The money from sales also becomes the property of the capitalist. The capitalist pays the workers a portion of this profit for their labor, pays other overhead costs, and keeps the rest. This profit may be used in a variety of ways, it may be consumed, or it may be used in pursuit of more profit such as by investing it in the development of new products or technological innovations, or expanding the business into new geographic territories. If more money is needed than the initial owners are willing or able to provide, the business may need to borrow a limited amount of extra money with a promise to pay it back with interest. In effect, it may rent more [[capital (economics)|capital]]. |

|||

* Capitalism 1.0 during the 19th century entailed largely unregulated markets with a minimal role for the state (aside from national defense, and protecting property rights); |

|||

* Capitalism 2.0 during the post-World War II years entailed Keynesianism, a substantial role for the state in regulating markets, and strong welfare states; |

|||

* Capitalism 2.1 entailed a combination of unregulated markets, globalization, and various national obligations by states. |

|||

==== Relationship to democracy ==== |

|||

The relationship between [[democracy]] and capitalism is a contentious area in theory and in popular political movements.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Milner |first1=Helen V |title=Is Global Capitalism Compatible with Democracy? Inequality, Insecurity, and Interdependence |journal=[[International Studies Quarterly]] |date=2021 |volume=65 |issue=4 |pages=1097–1110 |doi=10.1093/isq/sqab056 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The extension of adult-male [[suffrage]] in 19th-century Britain occurred along with the development of industrial capitalism and [[representative democracy]] became widespread at the same time as capitalism, leading capitalists to posit a causal or mutual relationship between them. However, according to some authors in the 20th-century, capitalism also accompanied a variety of political formations quite distinct from liberal democracies, including [[fascism|fascist]] regimes, [[Absolute monarchy|absolute monarchies]] and [[One-party state|single-party states]].<ref name="Burnham" /> [[Democratic peace theory]] asserts that democracies seldom fight other democracies, but others suggest this may be because of political similarity or stability, rather than because they are "democratic" or "capitalist". Critics argue that though economic growth under capitalism has led to democracy, it may not do so in the future as [[authoritarian]] régimes have been able to manage economic growth using some of capitalism's competitive principles<ref>{{cite magazine |first=Gady |last=Epstein |title=The Winners And Losers in Chinese Capitalism |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/gadyepstein/2010/08/31/the-winners-and-losers-in-chinese-capitalism/ |magazine=[[Forbes]] |access-date=28 October 2015 |archive-date=5 November 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151105210914/http://www.forbes.com/sites/gadyepstein/2010/08/31/the-winners-and-losers-in-chinese-capitalism/ |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=The rise of state capitalism |url=http://www.economist.com/node/21543160 |newspaper=[[The Economist]] |access-date=24 October 2015 |issn=0013-0613 |archive-date=15 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200615124603/https://www.economist.com/leaders/2012/01/21/the-rise-of-state-capitalism |url-status=live}}</ref> without making concessions to greater [[political freedom]].<ref>{{cite web |last=Mesquita |first=Bruce Bueno de |url=http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20050901faessay84507/bruce-bueno-de-mesquita-george-w-downs/development-and-democracy.html |title=Development and Democracy |date=September 2005 |access-date=26 February 2008 |work=[[Foreign Affairs]] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080220154505/http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20050901faessay84507/bruce-bueno-de-mesquita-george-w-downs/development-and-democracy.html |archive-date=20 February 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Siegle |first1=Joseph |last2=Weinstein |first2=Michael |last3=Halperin |first3=Morton |date=1 September 2004 |title=Why Democracies Excel |url=http://www.mafhoum.com/press7/212S28.pdf |journal=[[Foreign Affairs]] |volume=83 |issue=5 |pages=57 |doi=10.2307/20034067 |jstor=20034067 |access-date=26 August 2018 |archive-date=12 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190412055541/http://www.mafhoum.com/press7/212S28.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Political scientists [[Torben Iversen]] and [[David Soskice]] see democracy and capitalism as mutually supportive.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Iversen |first1=Torben |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv4g1r3n |title=Democracy and Prosperity: Reinventing Capitalism through a Turbulent Century |last2=Soskice |first2=David |date=2019 |publisher=[[Princeton University Press]] |jstor=j.ctv4g1r3n |isbn=978-0-691-18273-5}}</ref> [[Robert Dahl]] argued in ''On Democracy'' that capitalism was beneficial for democracy because economic growth and a large middle class were good for democracy.<ref name=":0a">{{cite book |last=Dahl |first=Robert A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZG4JEAAAQBAJ |title=On Democracy |date=2020 |publisher=[[Yale University Press]] |isbn=978-0-300-25799-1 |language=en}}</ref> He also argued that a market economy provided a substitute for government control of the economy, which reduces the risks of tyranny and authoritarianism.<ref name=":0a" /> |

|||