Furcula: Difference between revisions

m Journal cites:, added 1 PMID, added 1 PMC using AWB (12145) |

Neotaruntius (talk | contribs) Added an example, making the etymology clearer |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Forked bone found in birds and other dinosaurs; fusion of the two clavicles}} |

|||

{{About||the springtail appendage|Furcula (springtail)|the genus of moth|Furcula (moth)}} |

{{About||the springtail appendage|Furcula (springtail)|the genus of moth|Furcula (moth)|the genus of plant|Furcula (plant)}} |

||

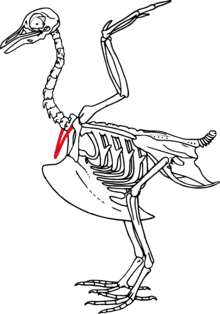

[[Image:Furcula.png|thumb|This stylised bird skeleton highlights the furcula]] |

[[Image:Furcula.png|thumb|This stylised bird skeleton highlights the furcula]] |

||

[[Image:Furcula.jpg|thumb|right|Wishbone of a [[chicken]]]] |

|||

The '''{{lang|la|furcula}}''' (" |

The '''{{lang|la|furcula|italics=no}}''' (Latin for "little fork"; {{plural form}}: '''furculae'''){{efn| In general the suffix ''-la'' represents a diminutive form of the original. For example novella is a short novel.}} or '''wishbone''' is a forked [[bone]] found in most [[bird]]s and some species of non-avian dinosaurs, and is formed by the fusion of the two [[clavicle]]s.<ref name="ornithology"></ref> In birds, its primary function is in the strengthening of the [[Thorax|thoracic]] [[skeleton]] to withstand the rigors of [[flight]]. |

||

==In birds== |

==In birds== |

||

The furcula works as a strut between a bird's shoulders, and articulates to each of the bird's [[scapulae]]. In conjunction with the [[coracoid]] and the scapula, it forms a unique structure called the triosseal canal, which houses a strong tendon that connects the [[Bird anatomy#Muscular system|supracoracoideus]] muscles to the [[humerus]]. This system is responsible for lifting the wings during the recovery stroke.<ref name="ornithology" /> |

The furcula works as a strut between a bird's shoulders, and articulates to each of the bird's [[scapulae]]. In conjunction with the [[coracoid]] and the scapula, it forms a unique structure called the triosseal canal, which houses a strong tendon that connects the [[Bird anatomy#Muscular system|supracoracoideus]] muscles to the [[humerus]]. This system is responsible for lifting the wings during the recovery stroke.<ref name="ornithology" /> |

||

As the thorax is compressed by the flight muscles during downstroke, the upper ends of the furcula spread apart, expanding by as much as 50% of its resting width, and then contracts.<ref name="ornithology">{{cite book| last1 = Gill| first1 = Frank B. | title = Ornithology| location = New York| publisher = W. H. Freeman and Company| year= 2007| pages = |

As the thorax is compressed by the flight muscles during downstroke, the upper ends of the furcula spread apart, expanding by as much as 50% of its resting width, and then contracts.<ref name="ornithology">{{cite book| last1 = Gill| first1 = Frank B. | title = Ornithology| url = https://archive.org/details/ornithologythird00gill| url-access = limited| location = New York| publisher = W. H. Freeman and Company| year= 2007| pages = [https://archive.org/details/ornithologythird00gill/page/n151 134]–136| isbn = 978-0-7167-4983-7 }}</ref> [[X-ray]] films of [[starling]]s in flight have shown that in addition to strengthening the thorax, the furcula acts like a spring in the pectoral girdle during flight. It expands when the wings are pulled downward and snaps back as they are raised. In this action, the furcula is able to store some of the energy generated by contraction in the breast muscles, expanding the shoulders laterally, and then releasing the energy during upstroke as the furcula snaps back to the normal position. This, in turn, draws the shoulders toward the midline of the body.<ref name="Manual">{{cite book| last1 = Proctor | first1 = Noble S. |last2 = Lynch |first2 = Patrick J.| title = Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure and Function| publisher = [[Yale University Press]]|date=October 1998| page = 214| isbn = 0-300-07619-3 }}</ref> While the starling has a moderately large and strong furcula for a bird of its size, there are many species where the furcula is completely absent, for instance [[scrubbird]]s, some [[toucan]]s and [[New World barbet]]s, some [[owl]]s, some [[parrot]]s, [[turaco]]s, and [[mesite]]s. These birds are still fully capable of flying. They also have close relatives where the furcula is vestigial, reduced to a thin strap of ossified ligament, seemingly purposeless. Other species have evolved the furcula in the opposite direction, so that it has increased in size and become too stiff or massive to act as a spring. In strong flyers like cranes and falcons, the arms of the furcula are large, hollow and quite rigid.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=YhAYWfPkJkQC&dq=%22birds+lack+a+furcula%22&pg=PA188 The Inner Bird: Anatomy and Evolution, by Gary W. Kaiser]</ref> |

||

In birds, the furcula also may aid in [[respiratory system|respiration]] by helping to pump air through the [[Bird anatomy#Respiratory system|air sacs]].<ref name="ornithology" /> |

In [[Bird anatomy|birds]], the furcula also may aid in [[respiratory system|respiration]] by helping to pump air through the [[Bird anatomy#Respiratory system|air sacs]].<ref name="ornithology" /> |

||

==In other animals== |

==In other animals== |

||

| ⚫ | Several groups of [[theropod]] dinosaurs have also been found with furculae, including [[Dromaeosauridae|dromaeosaurids]], [[Oviraptoridae|oviraptorid]]s,<ref name="encyclopedia">{{cite book| last1 = Currie | first1 = Philip J. |last2 = Padian |first2 = Kevin| title = Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs| url = https://archive.org/details/encyclopediadino00curr_075 | url-access = limited | publisher = Academic Press|date=October 1997| pages = [https://archive.org/details/encyclopediadino00curr_075/page/n560 530]–535| isbn = 0-12-226810-5 }}</ref> [[Tyrannosauridae|tyrannosaurids]],<ref>{{cite book| last1 = Carpenter | first1 = Kenneth| title = The Carnivorous Dinosaurs| url = https://archive.org/details/carnivorousdinos00carp | url-access = limited | publisher = Indiana University Press|date=July 2005| pages = [https://archive.org/details/carnivorousdinos00carp/page/n255 247]–255| isbn = 0-253-34539-1 }}</ref> [[Troodontidae|troodontids]], [[Coelophysidae|coelophysids]]<ref>{{cite journal| author = Tykoski, Ronald S.| title = A Furcula in the Coelophysid Theropod ''Syntarsis''| journal = Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology| volume = 22|issue=3 | pages = 728–733| date = September 2002| doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0728:afitct]2.0.co;2|display-authors=etal}}</ref> and [[Allosauroidea|allosauroid]]s.<ref name="encyclopedia" /> |

||

[[Image:Furcula evolution3.png|thumb|right|200px|Proposed evolutionary model of the furcula]] |

|||

| ⚫ | Several groups of [[theropod]] dinosaurs have also been found with furculae, including [[Dromaeosauridae|dromaeosaurids]], [[Oviraptoridae|oviraptorid]]s,<ref name="encyclopedia">{{cite book| last1 = Currie | first1 = Philip J. |last2 = Padian |first2 = Kevin| title = Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs| |

||

Seeing the occurrence in diplodocid dinosaurs of interclavicles, Tschopp and Mateus (2013) <ref>{{cite journal| |

Seeing the occurrence in [[diplodocid]] dinosaurs of [[Interclavicle|interclavicles]], Tschopp and Mateus (2013) <ref>{{cite journal|author1=Tschopp, E. |author2=Mateus O. |year=2013|title=Clavicles, interclavicles, gastralia, and sternal ribs in sauropod dinosaurs: new reports from Diplodocidae and their morphological, functional and evolutionary implications|journal=Journal of Anatomy|volume=222|issue=3|pages=321–340|doi=10.1111/joa.12012|pmid=23190365|pmc=3582252}}</ref> proposed that the furcula is a transformed and divided interclavicle, rather than a fused clavicle. |

||

==In folklore== |

==In folklore== |

||

[[ |

[[File:"Best Wishes for The New Year.".jpg|thumb|right|200px|New Year postcard from around 1909 featuring a wishbone as a [[List of lucky symbols|lucky symbol]]]] |

||

[[Superstition]]s surrounding [[divination]] by means of a [[goose]]'s wishbone go back to at least the [[Late Medieval Period]]. [[Johannes Hartlieb]] in 1455 recorded the divination of weather by means of a goose's wishbone, "When the goose has been eaten on [[St. Martin's Day]] or Night, the oldest and most sagacious keeps the breast-bone and allowing it to dry until the morning examines it all around, in front, behind and in the middle. Thereby they divine whether the winter will be severe or mild, dry or wet, and are so confident in their prediction that they will wager their goods and chattels on its accuracy.", and of a military officer: "This valiant man, this Christian Captain drew forth out of his doublet that heretical object of superstition, the goose-bone, and showed me that after [[Candlemas]] an exceeding severe frost should occur, and could not fail." The Captain also said, "Teutonic knights in Prussia waged all their wars by the goose-bone; and as the goose-bone predicted so did they order their two campaigns, one in summer and one in winter."<ref> |

[[Superstition]]s surrounding [[divination]] by means of a [[goose]]'s wishbone go back to at least the [[Late Medieval Period]]. [[Johannes Hartlieb]] in 1455 recorded the divination of weather by means of a goose's wishbone, "When the goose has been eaten on [[St. Martin's Day]] or Night, the oldest and most sagacious keeps the breast-bone and allowing it to dry until the morning examines it all around, in front, behind and in the middle. Thereby they divine whether the winter will be severe or mild, dry or wet, and are so confident in their prediction that they will wager their goods and chattels on its accuracy.", and of a military officer: "This valiant man, this Christian Captain drew forth out of his doublet that heretical object of superstition, the goose-bone, and showed me that after [[Candlemas]] an exceeding severe frost should occur, and could not fail." The Captain also said, "Teutonic knights in Prussia waged all their wars by the goose-bone; and as the goose-bone predicted so did they order their two campaigns, one in summer and one in winter."<ref>Edward A. Armstrong, ''The Folklore of Birds'' (1970), cited after {{cite news|last=Davis|first=Marcia|title=Wishbone myth has long history|url=http://www.knoxnews.com/news/2006/nov/19/davis-wishbone-myth-has-long-history/|access-date=27 September 2012|newspaper=Knoxville News Sentinel}}</ref> |

||

Edward A. Armstrong, ''The Folklore of Birds'' (1970), cited after {{cite news|last=Davis|first=Marcia|title=Wishbone myth has long history|url=http://www.knoxnews.com/news/2006/nov/19/davis-wishbone-myth-has-long-history/|accessdate=27 September 2012|newspaper=Knoxville News Sentinel}}</ref> |

|||

The custom of two persons pulling on the bone with the one receiving the larger part making a wish developed in the early 17th century. At that time, the name of the bone was a ''merrythought''. The name ''wishbone'' in reference to this custom is recorded from 1860.<ref>[[etymonline.com]]</ref> |

The custom of two persons pulling on the bone with the one receiving the larger part making a wish developed in the early 17th century. In some family traditions, the one receiving the smaller part made the wish. At that time, the name of the bone was a ''merrythought''. The name ''wishbone'' in reference to this custom is recorded from 1860.<ref>[[etymonline.com]]</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Bird anatomy]] |

*[[Bird anatomy]] |

||

==Footnotes== |

|||

{{notelist|1}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{commons category|Furcula}} |

|||

<references/> |

<references/> |

||

Latest revision as of 12:17, 3 January 2025

The furcula (Latin for "little fork"; pl.: furculae)[a] or wishbone is a forked bone found in most birds and some species of non-avian dinosaurs, and is formed by the fusion of the two clavicles.[1] In birds, its primary function is in the strengthening of the thoracic skeleton to withstand the rigors of flight.

In birds

[edit]The furcula works as a strut between a bird's shoulders, and articulates to each of the bird's scapulae. In conjunction with the coracoid and the scapula, it forms a unique structure called the triosseal canal, which houses a strong tendon that connects the supracoracoideus muscles to the humerus. This system is responsible for lifting the wings during the recovery stroke.[1]

As the thorax is compressed by the flight muscles during downstroke, the upper ends of the furcula spread apart, expanding by as much as 50% of its resting width, and then contracts.[1] X-ray films of starlings in flight have shown that in addition to strengthening the thorax, the furcula acts like a spring in the pectoral girdle during flight. It expands when the wings are pulled downward and snaps back as they are raised. In this action, the furcula is able to store some of the energy generated by contraction in the breast muscles, expanding the shoulders laterally, and then releasing the energy during upstroke as the furcula snaps back to the normal position. This, in turn, draws the shoulders toward the midline of the body.[2] While the starling has a moderately large and strong furcula for a bird of its size, there are many species where the furcula is completely absent, for instance scrubbirds, some toucans and New World barbets, some owls, some parrots, turacos, and mesites. These birds are still fully capable of flying. They also have close relatives where the furcula is vestigial, reduced to a thin strap of ossified ligament, seemingly purposeless. Other species have evolved the furcula in the opposite direction, so that it has increased in size and become too stiff or massive to act as a spring. In strong flyers like cranes and falcons, the arms of the furcula are large, hollow and quite rigid.[3]

In birds, the furcula also may aid in respiration by helping to pump air through the air sacs.[1]

In other animals

[edit]Several groups of theropod dinosaurs have also been found with furculae, including dromaeosaurids, oviraptorids,[4] tyrannosaurids,[5] troodontids, coelophysids[6] and allosauroids.[4]

Seeing the occurrence in diplodocid dinosaurs of interclavicles, Tschopp and Mateus (2013) [7] proposed that the furcula is a transformed and divided interclavicle, rather than a fused clavicle.

In folklore

[edit]

Superstitions surrounding divination by means of a goose's wishbone go back to at least the Late Medieval Period. Johannes Hartlieb in 1455 recorded the divination of weather by means of a goose's wishbone, "When the goose has been eaten on St. Martin's Day or Night, the oldest and most sagacious keeps the breast-bone and allowing it to dry until the morning examines it all around, in front, behind and in the middle. Thereby they divine whether the winter will be severe or mild, dry or wet, and are so confident in their prediction that they will wager their goods and chattels on its accuracy.", and of a military officer: "This valiant man, this Christian Captain drew forth out of his doublet that heretical object of superstition, the goose-bone, and showed me that after Candlemas an exceeding severe frost should occur, and could not fail." The Captain also said, "Teutonic knights in Prussia waged all their wars by the goose-bone; and as the goose-bone predicted so did they order their two campaigns, one in summer and one in winter."[8]

The custom of two persons pulling on the bone with the one receiving the larger part making a wish developed in the early 17th century. In some family traditions, the one receiving the smaller part made the wish. At that time, the name of the bone was a merrythought. The name wishbone in reference to this custom is recorded from 1860.[9]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ In general the suffix -la represents a diminutive form of the original. For example novella is a short novel.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gill, Frank B. (2007). Ornithology. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-0-7167-4983-7.

- ^ Proctor, Noble S.; Lynch, Patrick J. (October 1998). Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure and Function. Yale University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0-300-07619-3.

- ^ The Inner Bird: Anatomy and Evolution, by Gary W. Kaiser

- ^ a b Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (October 1997). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 530–535. ISBN 0-12-226810-5.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (July 2005). The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 247–255. ISBN 0-253-34539-1.

- ^ Tykoski, Ronald S.; et al. (September 2002). "A Furcula in the Coelophysid Theropod Syntarsis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 728–733. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0728:afitct]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Tschopp, E.; Mateus O. (2013). "Clavicles, interclavicles, gastralia, and sternal ribs in sauropod dinosaurs: new reports from Diplodocidae and their morphological, functional and evolutionary implications". Journal of Anatomy. 222 (3): 321–340. doi:10.1111/joa.12012. PMC 3582252. PMID 23190365.

- ^ Edward A. Armstrong, The Folklore of Birds (1970), cited after Davis, Marcia. "Wishbone myth has long history". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ etymonline.com