Hundred Years' War: Difference between revisions

→Battle of Agincourt (1415): Siege of Harfleur link |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Medieval Anglo-French conflicts, 1337–1453}} |

|||

{{FixHTML|beg}} |

|||

{{About||the earlier Anglo-French conflict|First Hundred Years' War|the later Anglo-French conflict|Second Hundred Years' War|the war between the Kingdom of Croatia and the Ottoman Empire|Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War}} |

|||

{{Infobox Military Conflict |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2022}} |

|||

|conflict= Hundred Years' War |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=April 2023}} |

|||

|image=[[File:Hundred Years' War montage.jpg|300px|Hundred Years' War]] |

|||

{{Infobox military conflict |

|||

|caption=Clockwise, from top left: [[John of Bohemia]] at the [[Battle of Crécy]], English and Franco-Castilian fleets at the [[Battle of La Rochelle]], [[Henry V of England|Henry V]] and the Plantagenet army at the [[Battle of Agincourt]],<br />[[Joan of Arc]] rallies French forces at the [[Siege of Orléans]] |

|||

| conflict = Hundred Years' War |

|||

|date= 1337–1453 |

|||

| |

| partof = the [[Crisis of the late Middle Ages]] and the [[Anglo-French Wars]] |

||

| width = |

|||

|result = Valoisian victory,<br />House of Valois established as ruling dynasty of France. |

|||

| image = Hundred years war collage.jpg |

|||

|territory=House of Valois secures control of all France except [[Pale of Calais]] |

|||

| image_size = 300 |

|||

|combatant1=[[Image:Blason France moderne.svg|15px]] [[House of Valois]]<br />[[Image:Escudo Corona de Castilla.png|15px]] [[Crown of Castile|Castile]]<br />[[Image:Royal coat of arms of Scotland.svg|15px]] [[Kingdom of Scotland|Scotland]]<br />[[Image:CoA civ ITA genova.png|15px]] [[Republic of Genoa|Genoa]]<br />[[Image:Armoiries Majorque.svg|15px]] [[Kingdom of Majorca|Majorca]]<br />[[Image:Small coat of arms of the Czech Republic.svg|15px]] [[Kingdom of Bohemia|Bohemia]]<br />[[File:Aragon Arms.svg|15px]] [[Crown of Aragon]]<br />[[Image:COA fr BRE.svg|15px]] [[Duchy of Brittany|Brittany]] |

|||

| caption = Clockwise, from top left: the [[Battle of La Rochelle]], the [[Battle of Agincourt]], the [[Battle of Patay]], and [[Joan of Arc]] at the [[Siege of Orléans]] |

|||

|combatant2=[[Image:England Arms 1340.svg|15px]] [[House of Plantagenet]]<br /> [[Image:Blason fr Bourgogne.svg|15px]] [[Duchy of Burgundy|Burgundy]]<br />[[Image:Blason de l'Aquitaine et de la Guyenne.svg|15px]] [[Aquitaine]]<br />[[Image:COA fr BRE.svg|15px]] [[Brittany]]<br />[[File:Armoires portugal 1385.png|15px]] [[Kingdom of Portugal|Portugal]]<br />[[Image:Blason Royaume Navarre.svg|15px]] [[Navarre]]<br />[[Image:Blason Nord-Pas-De-Calais.svg|15px]] [[Flanders]]<br />[[Image:Hainaut Modern Arms.svg|15px]] [[County of Hainaut|Hainaut]]<br />[[Image:Luxembourg New Arms.svg|15px]] [[Luxembourg]]<br />[[Image:Holy Roman Empire Arms-single head.svg|15px]] [[Holy Roman Empire]]|strength1= |

|||

| date = 24 May 1337 – 19 October 1453 (intermittent){{Efn|24 May 1337 is the day when [[Philip VI of France]] confiscated [[Duchy of Aquitaine|Aquitaine]] from [[Edward III of England]], who responded by claiming the French throne. [[Bordeaux]] fell to the French on 19 October 1453; there were no more hostilities afterwards.}} {{nwr|({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|month1=05|day1=24|year1=1337|month2=10|day2=19|year2=1453|df=y}})}} |

|||

|strength2= |

|||

| place = [[France]], the [[Low Countries]], [[Great Britain]], the [[Iberian Peninsula]] |

|||

|casualties1= |

|||

| result = French victory |

|||

|casualties2 |

|||

| territory = [[Kingdom of England|England]] loses all [[Duchy of Gascony|continental possessions]] except for the [[Pale of Calais]]. |

|||

|notes= |

|||

| combatant1 = [[Kingdom of France]] loyal to the [[House of Valois]] |

|||

| combatant1a = {{ubl |

|||

| [[Burgundian State]] (1337–1419; 1435–1453) |

|||

| [[Duchy of Brittany]] |

|||

| [[Crown of Castile]] |

|||

| [[Kingdom of Scotland]] |

|||

| [[Glyndŵr Rising|Welsh rebels]] |

|||

| [[Crown of Aragon]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| combatant2 = |

|||

[[Kingdom of England]] |

|||

*[[Kingdom of France]] loyal to the [[House of Plantagenet]] |

|||

|combatant2a={{ubl |

|||

| [[Burgundian State]] (1419–1435) |

|||

| [[Duchy of Brittany]] |

|||

| [[Kingdom of Portugal]] |

|||

| [[Kingdom of Navarre]] |

|||

| [[Duchy of Gascony]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| commander1 = {{Plainlist}} |

|||

* [[Philip VI of France|Philip VI]] [[Death by natural causes|#]] |

|||

* [[John II of France|John II]]{{Surrendered}} |

|||

* [[Charles V of France|Charles V]] [[Death by natural causes|#]] |

|||

* [[Charles VI of France|Charles VI]] [[Death by natural causes|#]] |

|||

* [[Charles VII of France|Charles VII]] |

|||

* [[Louis XI of France|Louis, Dauphin]] |

|||

* [[Joan of Arc]]{{Executed}} |

|||

* [[Gilles de Rais]] |

|||

* [[Bertrand du Guesclin]] |

|||

* [[Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy|Philip the Bold]] |

|||

* [[John the Fearless]] |

|||

* [[Owain Glyndŵr]] |

|||

* [[Philip the Good]] |

|||

* [[Charles, Duke of Brittany|Charles of Blois]]{{KIA}} |

|||

* [[David II of Scotland|David II]]{{Surrendered}} |

|||

* [[John Stewart, Earl of Buchan|John Stewart]]{{KIA}} |

|||

* [[Henry of Trastámara]] |

|||

* [[John I of Castile|John I]] |

|||

{{Endplainlist}} |

|||

| commander2 = {{Plainlist}} |

|||

* [[Edward III of England|Edward III]] [[Death by natural causes|#]] |

|||

* [[Richard II of England|Richard II]]{{assassinated}} |

|||

* [[Henry IV of England|Henry IV]] [[Death by natural causes|#]] |

|||

* [[Henry V of England|Henry V]] [[Death by natural causes|#]] |

|||

* [[Henry VI of England|Henry VI]] |

|||

* [[Edward the Black Prince|The Black Prince]] |

|||

* [[John of Gaunt]] |

|||

* [[Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York|Richard of York]] |

|||

* [[John, Duke of Bedford|John of Lancaster]] |

|||

* [[Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster|Henry of Lancaster]] |

|||

* [[Jean III de Grailly]]{{Surrendered}} |

|||

* [[Thomas Montagu, 4th Earl of Salisbury|Thomas Montacute]]{{KIA}} |

|||

* [[John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury|John Talbot]]{{KIA}} |

|||

* [[John Fastolf]] |

|||

* [[Robert III of Artois|Robert d'Artois]] |

|||

* [[Philip the Good]] |

|||

* [[John of Montfort]] |

|||

{{Endplainlist}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{FixHTML|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Hundred Years' War}} |

|||

{{FixHTML|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Edwardian War}} |

{{Campaignbox Edwardian War}} |

||

{{Campaignbox Breton War of Succession}} |

|||

{{FixHTML|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Caroline War}} |

{{Campaignbox Caroline War}} |

||

{{FixHTML|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Lancastrian War}} |

{{Campaignbox Lancastrian War}} |

||

{{Campaignbox Hundred Years' War}} |

|||

{{FixHTML|end}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Anglo-French wars}} |

|||

The '''Hundred Years' War''' ({{ |

The '''Hundred Years' War''' ({{Langx|fr|link=yes|Guerre de Cent Ans}}; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of [[Kingdom of England|England]] and [[Kingdom of France|France]] and a civil war in France during the [[Late Middle Ages]]. It emerged from feudal disputes over the [[Duchy of Aquitaine]] and was triggered by [[English claims to the French throne|a claim to the French throne]] made by [[Edward III of England]]. The war grew into a broader military, economic, and political struggle involving factions from across [[Western Europe]], fuelled by emerging [[nationalism]] on both sides. The periodisation of the war typically charts it as taking place over 116 years. However, it was an intermittent conflict which was frequently interrupted by external factors, such as the [[Black Death]], and several years of [[Ceasefire|truces]]. |

||

The Hundred Years' War was a significant conflict in the [[Middle Ages]]. During the war, five generations of kings from two rival [[Dynasty|dynasties]] fought for the throne of France, which was then the dominant kingdom in Western Europe. The war had a lasting effect on European history: both sides produced innovations in military technology and tactics, including professional standing armies and artillery, that permanently changed European warfare. [[Chivalry]], which reached its height during the conflict, subsequently declined. Stronger [[National identity|national identities]] took root in both kingdoms, which became more centralized and gradually emerged as [[List of modern great powers#Early modern powers|global powers]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Guizot |first=Francois |title=The History of Civilization in Europe; translated by William Hazlitt 1846 |publisher=Liberty Fund |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-86597-837-9 |location=Indiana, US |pages=204, 205}}</ref> |

|||

The conflict lasted 116 years but was punctuated by several periods of peace, before it finally ended in the expulsion of the [[Plantagenet]]s from France (except the [[Pale of Calais]]). The war was eventually a victory for the house of Valois, who succeeded in recovering the Plantagenet gains made initially and expelling them from the majority of France by the 1450s. However, the war nearly ruined the Valois, while the Plantagenets gained huge amounts of plunder from the mainland, which enriched England. France itself likewise suffered greatly from the war, as most of the conflict occurred on the continent. |

|||

The term "Hundred Years' War" was adopted by later historians as a [[Historiography|historiographical]] [[periodisation]] to encompass dynastically related conflicts, constructing the longest military conflict in [[History of Europe|European history]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rehman |first=Iskander |title=Planning for Protraction: A Historically Informed Approach to Great-power War and Sino-US Competition |date=2023-11-08 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |isbn=978-1-003-46441-9 |edition=1 |location=London |pages=146 |language=en |doi=10.4324/9781003464419 |quote=The term 'Hundred Years War' was first employed by the French historian Chrysanthe-Ovide des Michels in his ''Tableau Chronologique de L'histoire du Moyen Âge''. It was then imported into English historiography by the English historian [[Edward Augustus Freeman|Edward Freeman]].}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Minois |first=Georges |title=La guerre de Cent Ans |date=2024-03-28 |publisher=Place des éditeurs |isbn=978-2-262-10723-9 |language=fr}}</ref> The war is commonly divided into three phases separated by truces: the [[Hundred Years' War (1337–1360)|Edwardian War]] (1337–1360), the [[Hundred Years' War (1369–1389)|Caroline War]] (1369–1389), and the [[Hundred Years' War, 1415–1453|Lancastrian War]] (1415–1453). Each side drew many [[Alliance|allies]] into the conflict, with English forces initially prevailing; however, the French forces under the [[House of Valois]] ultimately retained control over the Kingdom of France. The French and English monarchies thereafter remained separate, despite the [[List of English monarchs|monarchs of England]] (later [[United Kingdom|Britain]]) styling themselves as [[English claims to the French throne|sovereigns of France]] until [[English claims to the French throne#Ending the claim|1802]]. |

|||

The war was in fact a series of conflicts and is commonly divided into three or four phases: the [[Hundred Years' War (1337–1360)|Edwardian War (1337–1360)]], the [[Hundred Years' War (1369–1389)|Caroline War (1369–1389)]], the [[Hundred Years' War (1415–1429)|Lancastrian War (1415–1429)]], and the slow decline of English fortunes after the appearance of [[Joan of Arc]] (1412–1431). Several other contemporary European conflicts were directly related to this conflict: the [[Breton War of Succession]], the [[Castilian Civil War]], the [[War of the Two Peters]], and the [[1383-1385 Crisis]]. The term "Hundred Years' War" was a later term invented by historians to describe the series of events. |

|||

== Overview == |

|||

The war owes its historical significance to a number of factors. Though primarily a dynastic conflict, the war gave impetus to ideas of both French and English [[nationalism]]. Militarily, it saw the introduction of new weapons and tactics, which eroded the older system of [[feudal]] armies dominated by [[heavy cavalry]]. The first [[standing army|standing armies]] in [[Western Europe]] since the time of the [[Western Roman Empire]] were introduced for the war, thus changing the role of the peasantry. For all this, as well as for its long duration, it is often viewed as one of the most significant conflicts in the history of [[medieval warfare]]. In France, the [[England|English]] [[invasion]], civil wars, deadly [[List of epidemics|epidemics]], [[famine]]s and marauding [[mercenary]] armies (turned to banditry) reduced the population by two-thirds.<ref>Don O'Reilly. "[http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history/3031536.html Hundred Years' War: Joan of Arc and the Siege of Orléans]". ''TheHistoryNet.com''.</ref> Shorn of its Continental possessions, England was left an island nation, a fact which profoundly affected its outlook and development for more than 500 years.<ref>As noted in, ''e.g.'', Gregory D. Cleva, ''Henry Kissinger and the American Approach to Foreign Policy'', Bucknell University Press, 1989; p. 87 ("the English Channel gave the nation a sense of geographical remoteness" while its "navy fostered a sense of physical unassailability" that lasted until the early 20th century).</ref> |

|||

[[File:TimeLine100YearsWar (cropped).png|thumb|500px|A [[Timeline of the Hundred Years' War|timeline]] of the key events of the Hundred Years' War]] |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date = January 2022}} |

|||

== |

=== Origins === |

||

The root causes of the conflict can be traced to the [[Crisis of the Late Middle Ages|crisis of 14th-century Europe]]. The outbreak of war was motivated by a gradual rise in tension between the kings of France and England over territory; the official pretext was the interruption of the direct male line of the [[Capetian dynasty]]. |

|||

The background to the conflict is to be found in 1066, when [[William I of England|William, Duke of Normandy]], led an [[Norman Conquest|invasion of England]]. He defeated the [[Anglo-Saxon|English]] [[Harold Godwinson|King Harold II]] at the [[Battle of Hastings]], and had himself crowned King of England. As Duke of Normandy, he remained a [[vassal]] of the French King, and was required to swear [[fealty]] to the latter for his lands in France; for a King to swear fealty to another King was considered humiliating, and the [[Norman Kings]] of England generally attempted to avoid the service. On the French side, the Capetian monarchs resented a neighbouring king holding lands within their own realm, and sought to neutralise the threat England now posed to France. |

|||

Tensions between the French and English crowns had gone back centuries to the origins of the English royal family, which was French ([[Normans|Norman]], and later, [[Angevin kings of England|Angevin]]) in origin through [[William the Conqueror]], the Norman duke who became King of England in 1066. English monarchs had, therefore, historically held [[Angevin Empire|titles and lands within France]], which made them [[vassal]]s to the kings of France. The status of the English king's French [[fief]]s was a significant source of conflict between the two monarchies throughout the Middle Ages. French monarchs systematically sought to check the growth of English power, stripping away lands as the opportunity arose, mainly whenever England was at war with [[Kingdom of Scotland|Scotland]], an [[Auld Alliance|ally of France]]. English holdings in France had varied in size, at some points dwarfing even the [[Crown lands of France|French royal domain]]; by 1337, however, only [[Guyenne]] and [[Gascony]] were English. |

|||

Following a period of [[civil war]]s and unrest in England known as [[The Anarchy]] (1135–1154), the Anglo-Norman dynasty was succeeded by the [[Angevin]] Kings. At the height of power the Angevins controlled Normandy and England, along with [[Maine (province of France)|Maine]], [[Anjou]], [[Touraine]], [[Poitou]], [[Gascony]], [[Saintonge]], and [[Aquitaine]]. The King of England directly ruled more territory on the continent than the King of France himself. This situation – where the Angevin kings owed [[vassalage]] to a ruler who was ''de facto'' much weaker – was a cause of continual conflict. This assemblage of lands is sometimes known as the [[Angevin Empire]]. |

|||

In 1328, [[Charles IV of France]] died without any sons or brothers, and a new principle, [[Salic Law#The succession in 1316|Salic law]], disallowed female succession. Charles's closest male relative was his nephew [[Edward III of England]], whose mother, [[Isabella of France|Isabella]], was Charles's sister. Isabella [[English claims to the French throne|claimed the throne of France for her son]] by the rule of [[proximity of blood]], but the French nobility rejected this, maintaining that Isabella [[Nemo dat quod non habet|could not transmit a right she did not possess]]. An assembly of French [[Baron|barons]] decided that a [[French people|native Frenchman]] should receive the crown, rather than Edward.{{Sfn|Previté-Orton|1978|p=872}} |

|||

[[John of England]] inherited this great estate from [[Richard I of England|King Richard I]]. However, [[Philip II of France]] acted decisively to exploit the weaknesses of King John, both legally and militarily, and by 1204 had succeeded in wresting control of most of the ancient territorial possessions. The subsequent [[Battle of Bouvines]] (1214), along with the [[Saintonge War]] (1242) and finally the [[War of Saint-Sardos]] (1324), reduced Angevin hold on the continent to a few small provinces in Gascony, and the complete loss of the crown jewel of Normandy. |

|||

The throne passed to Charles's [[Patrilineality|patrilineal]] cousin instead, [[Philip VI of France|Philip]], [[Counts and dukes of Valois|Count of Valois]]. Edward protested but ultimately submitted and did homage for Gascony. Further French disagreements with Edward induced Philip, during May 1337, to meet with his Great Council in Paris. It was agreed that Gascony should be taken back into Philip's hands, which prompted Edward to renew his claim for the French throne, this time by force of arms.{{Sfn|Previté-Orton|1978|pages=873–876}} |

|||

By the early 14th century, many in the English aristocracy could still remember a time when their grandparents and great-grandparents had control over wealthy continental regions, such as Normandy, which they also considered their ancestral homeland, and were motivated to regain possession of these territories. |

|||

=== Edwardian phase === |

|||

==Dynastic turmoil: 1314–1328==<!-- This section is linked from [[Edward III of England]] --> |

|||

In the early years of the war, the English, led by their king and his son [[Edward, the Black Prince]], saw resounding successes, notably at [[Battle of Crécy|Crécy]] (1346) and at [[Battle of Poitiers|Poitiers]] (1356), where King [[John II of France]] was taken prisoner. |

|||

The specific events leading up to the war took place in France, where the unbroken line of the [[House of Capet|Direct Capetian]] firstborn sons had succeeded each other for centuries. It was the longest continuous dynasty in medieval Europe. In 1314, the Direct Capetian, King [[Philip IV of France|Philip IV]], died, leaving three male heirs: [[Louis X of France|Louis X]], [[Philip V of France|Philip V]], and [[Charles IV of France|Charles IV]]. A fourth child of Phillip IV, [[Isabella of France|Isabella]], was married to [[Edward II of England]], and in 1312 had produced a son, Edward of Windsor, who was a potential heir to the thrones of both England (through his father) and France (through his grandfather). |

|||

=== Caroline phase and Black Death === |

|||

Philip IV's eldest son and heir, Louis X, died in 1316, leaving only his posthumous son [[John I of France|John I]], who was born and died that same year, and a daughter [[Joan II of Navarre|Joan]], whose paternity was suspect. |

|||

By 1378, under King [[Charles V of France|Charles V]] the Wise and the leadership of [[Bertrand du Guesclin]], the French had reconquered most of the lands ceded to King Edward in the [[Treaty of Brétigny]] (signed in 1360), leaving the English with only a few cities on the continent. |

|||

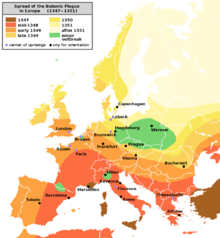

In the following decades, the weakening of royal authority, combined with the devastation caused by the [[Black Death]] of 1347–1351 (which killed nearly half of France{{Sfn|Turchin|2003|pp=179–180}} and 20–33% of England{{Sfn|Neillands|2001|pp=110–111}}) and the significant economic crisis that followed, led to a period of civil unrest in both countries. These crises were resolved in England earlier than in France. |

|||

Upon the deaths of Louis X and John I, Philip IV's second-eldest son, Philip V, sought the throne for himself, using rumours that his niece Joan was a result of her mother's adultery (and thus barred from the succession). A by-product of this was the invocation in the 1380s of [[Salic law]] to assert that women could not inherit the French throne.<ref>The Salic Law was not invoked until the 1380s - see Robin Neillands, The Hundred Years' War, Routledge.</ref> When Philip V himself died in 1322, his daughters, too, were put aside in favour of an uncle: Charles IV, the third son of Philip IV. |

|||

=== Lancastrian phase and after === |

|||

In 1324, Charles IV of France and his brother-in-law, Edward II of England fought the short [[War of Saint-Sardos]] in [[Gascony]]. The major event of the war was the brief siege of the English fortress of [[La Réole]], on the [[Garonne]]. The English forces, led by [[Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent|Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent]], were forced to surrender after a month of bombardment from the French cannons, after promised reinforcements never arrived. The war was a complete failure for England, and only [[Bordeaux]] and a narrow coastal strip of the once great [[Duchy of Aquitaine]] remained in English hands. |

|||

The newly crowned [[Henry V of England]] seized the opportunity presented by the mental illness of [[Charles VI of France]] and the [[Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War|French civil war between Armagnacs and Burgundians]] to revive the conflict. Overwhelming victories at [[Battle of Agincourt|Agincourt]] (1415) and [[Battle of Verneuil|Verneuil]] (1424), as well as an alliance with the Burgundians raised the prospects of an ultimate English triumph and persuaded the English to continue the war over many decades. A variety of factors prevented this, however. Notable influences include the deaths of both Henry and Charles in 1422, the emergence of [[Joan of Arc]] (which boosted French morale), and the loss of [[Burgundian State|Burgundy]] as an ally (concluding the French civil war). |

|||

The [[Siege of Orléans]] (1429) made English aspirations for conquest all but infeasible. Despite Joan's capture by the Burgundians and her subsequent execution (1431), a series of crushing French victories concluded the siege, favoring the Valois dynasty. Notably, [[Battle of Patay|Patay]] (1429), [[Battle of Formigny|Formigny]] (1450), and [[Battle of Castillon|Castillon]] (1453) proved decisive in ending the war. England permanently lost most of its continental possessions, with only the [[Pale of Calais]] remaining under its control on the continent until the [[Siege of Calais (1558)|Siege of Calais]] (1558). |

|||

The recovery of these lost lands became a major focus of English diplomacy. The war also galvanised opposition to Edward II among the English nobility and led to his being [[Deposition (politics)|deposed]] from the throne in 1327, in favour of his young son, Edward of Windsor, who thus became [[Edward III of England|Edward III]]. Charles IV died in 1328, leaving only a daughter, and an unborn infant who would prove to be a girl. The senior line of the [[Capetian dynasty]] thus ended, creating a crisis over the French succession. |

|||

=== Related conflicts and after-effects === |

|||

Meanwhile in England, the young Edward of Windsor had become King Edward III of England in 1327. Being also the nephew of Charles IV of France, Edward was Charles' closest living male relative, and the only surviving male descendent of Philip IV. By the English interpretation of feudal law, this made Edward III the legitimate [[heir to the throne]] of France. |

|||

Local conflicts in neighbouring areas, which were contemporarily related to the war, including the [[War of the Breton Succession]] (1341–1364), the [[Castilian Civil War]] (1366–1369), the [[War of the Two Peters]] (1356–1369) in [[Crown of Aragon|Aragon]], and the [[1383–1385 crisis]] in [[Kingdom of Portugal|Portugal]], were used by the parties to advance their agendas. |

|||

[[Image:Hundred Years War family tree.png|thumb|400px|Family tree relating the French and English royal houses at the beginning of the war]] |

|||

By the war's end, feudal armies had mainly been replaced by professional troops, and aristocratic dominance had yielded to a democratization of the manpower and weapons of armies. Although primarily a [[War of succession|dynastic conflict]], the war inspired [[French nationalism|French]] and [[English nationalism#Medieval|English]] nationalism. The broader introduction of weapons and tactics supplanted the [[feudalism|feudal]] armies where [[heavy cavalry]] had dominated, and [[artillery]] became important. The war precipitated the creation of the first [[standing army|standing armies]] in Western Europe since the [[Western Roman Empire]] and helped change their [[Military science|role in warfare]]. |

|||

The French nobility, however, balked at the prospect of a foreign king, particularly one who was also king of England. They asserted, based on their interpretation of the ancient [[Salic Law]], that the royal inheritance could not pass to a woman or through her to her offspring. Therefore, the most senior male of the Capetian dynasty after Charles IV, [[Philip VI of France|Philip of Valois]], grandson of Philip III of France, was the legitimate heir in the eyes of the French. He had taken regency after Charles IV's death and was allowed to take the throne after Charles' widow gave birth to a daughter. Philip of Valois was crowned as Philip VI, the first of the [[House of Valois]], a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. |

|||

Civil wars, deadly epidemics, famines, and bandit free-companies of mercenaries reduced the population drastically in France. But at the end of the war, the French had the upper hand due to their better supply, such as small hand-held cannons, weapons, etc. In England, political forces over time came to oppose the costly venture. After the war, England was left insolvent, leaving the conquering French in complete control of all of France except Calais. The dissatisfaction of [[History of the British peerage|English nobles]], resulting from the loss of their continental landholdings, as well as the general shock at losing a war in which investment had been so significant, helped lead to the [[Wars of the Roses]] (1455–1487). The economic consequences of the Hundred Years' War not only produced a decline in trade but also led to a high collection of taxes from both countries, which played a significant role in civil disorder. |

|||

[[Joan II of Navarre]], the daughter of Louis X, also had a good legal claim to the French throne, but lacked the power to back it up. The [[Kingdom of Navarre]] had no precedent against female rulers (the House of Capet having inherited it through Joan's grandmother, [[Joan I of Navarre]]), and so by treaty she and her husband, [[Philip III of Navarre|Philip of Evreux]], were permitted to inherit that Kingdom; however, the same treaty forced Joan and her husband to accept the accession of Philip VI in France, and to surrender her hereditary French domains of Champagne and Brie to the French crown in exchange for inferior estates. Joan and Philip of Evreux then produced a son, [[Charles II of Navarre]]. Born in 1332, Charles replaced Edward III as Philip IV's male heir in [[primogeniture]], and in proximity to Louis X; although Edward remained the male heir in proximity to Saint Louis, Philip IV, and Charles IV. |

|||

== Causes and prelude == |

|||

==On the eve of war: 1328–1337== |

|||

After Philip's accession, the English still controlled [[Gascony]]. Gascony produced vital shipments of [[salt]] and [[wine]], and was very profitable. It was a separate [[fief]], held of the French crown, rather than a territory of England. The [[Homage (medieval)|Homage]] done for its possession was a bone of contention between the two kings. Philip VI demanded Edward's recognition as sovereign; Edward wanted the return of further lands lost by his father. A compromise "homage" in 1329 pleased neither side; but in 1331, facing serious problems at home, Edward accepted Philip as King of France and gave up his claims to the French throne. In effect, England kept Gascony, in return for Edward giving up his claims to be the rightful king of France. |

|||

=== Dynastic turmoil in France: 1316–1328 === |

|||

In 1333, Edward III went to war against [[David II of Scotland]], a French ally under the [[Auld Alliance]], and began the [[Second War of Scottish Independence]]. Philip saw the opportunity to reclaim Gascony while England's attention was concentrated northwards. However, the war was, initially at least, a quick success for England, and David was forced to flee to France after being defeated by King Edward and [[Edward Balliol]] at the [[Battle of Halidon Hill]] in July. In 1336, Philip made plans for an expedition to restore David to the Scottish throne, and to also seize Gascony. |

|||

<!-- This section is linked from Edward III of England --> |

|||

{{Main|English claims to the French throne}} |

|||

The question of female succession to the French throne was raised after the death of [[Louis X of France|Louis X]] in 1316. Louis left behind a young daughter, [[Joan II of Navarre]], and a son, [[John I of France]], although he only lived for five days. However, Joan's paternity was in question, as her mother, [[Margaret of Burgundy, Queen of France|Margaret of Burgundy]], was accused of being an adulterer in the [[Tour de Nesle affair]]. Given the situation, Philip, [[Count of Poitiers]] and brother of Louis X, positioned himself to take the crown, advancing the stance that women should be ineligible to succeed to the French throne. He won over his adversaries through his political sagacity and succeeded to the French throne as [[Philip V of France|Philip V]]. When he died in 1322, leaving only daughters behind, the crown passed to his younger brother, [[Charles IV of France|Charles IV]].{{Sfn|Brissaud|1915|pp=329–330}} |

|||

==Beginning of the war: 1337–1360== |

|||

{{Hundred Years' War family tree}} |

|||

Charles IV died in 1328, leaving behind his young daughter and pregnant wife, [[Joan of Évreux]]. He decreed that he would become king if the unborn child were male. If not, Charles left the choice of his successor to the nobles. Joan gave birth to a girl, [[Blanche of France, Duchess of Orléans|Blanche of France]] (later Duchess of Orleans). With Charles IV's death and Blanche's birth, the main male line of the [[House of Capet]] was rendered extinct. |

|||

By [[proximity of blood]], the nearest male relative of Charles IV was his nephew, [[Edward III of England]]. Edward was the son of [[Isabella of France|Isabella]], the sister of the dead Charles IV, but the question arose whether she could transmit a right to inherit that she did not possess. Moreover, the French nobility balked at the prospect of being ruled by an Englishman, especially one whose mother, Isabella, and her lover, [[Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March|Roger Mortimer]], were widely suspected of having murdered the previous English king, [[Edward II of England|Edward II]]. The French barons, prelates, and the [[University of Paris]] assemblies decided that males who derive their right to inheritance through their mother should be excluded from consideration. Therefore, excluding Edward, the nearest [[Agnatic primogeniture|heir through the male line]] was Charles IV's first cousin, Philip, [[Counts and dukes of Valois|Count of Valois]], and it was decided that he should take the throne. He was crowned [[Philip VI of France|Philip VI]] in 1328. In 1340, the [[Avignon papacy]] confirmed that, under [[Salic law]], males would not be able to inherit through their mothers.{{Sfn|Brissaud|1915|pp=329–330}}{{Sfn|Previté-Orton|1978|p=872}} |

|||

Eventually, Edward III reluctantly recognized Philip VI and paid him [[Homage (feudal)|homage]] for the duchy of [[Duchy of Aquitaine|Aquitaine]] and [[Duchy of Gascony|Gascony]] in 1329. He made concessions in [[Guyenne]] but reserved the right to reclaim territories arbitrarily confiscated. After that, he expected to be left undisturbed while he made [[Second War of Scottish Independence|war on Scotland]]. |

|||

=== Dispute over Guyenne: a problem of sovereignty === |

|||

{{Main|First Hundred Years' War}} |

|||

{{Further|Peerage of France}} |

|||

[[File:Hommage d Édouard Ier à Philippe le Bel.jpg|thumb|Homage of [[Edward I of England]] (kneeling) to [[Philip IV of France]] (seated), 1286. As [[Duke of Aquitaine]], Edward was also a vassal to the French king (illumination by [[Jean Fouquet]] from the ''[[Grandes Chroniques de France]]'' in the [[Bibliothèque Nationale de France]], Paris).]] |

|||

Tensions between the French and English monarchies can be traced back to the 1066 [[Norman Conquest]] of England, in which the [[Throne of England|English throne]] was seized by the [[Duke of Normandy]], a [[vassal]] of the [[List of French monarchs|King of France]]. As a result, the crown of England was held by a succession of nobles who already owned lands in France, which put them among the most influential subjects of the French king, as they could now draw upon the economic power of England to enforce their interests in the mainland. To the kings of France, this threatened their royal authority, and so they would constantly try to undermine English rule in France, while the [[List of English monarchs|English monarchs]] would struggle to protect and expand their lands. This clash of interests was the root cause of much of the conflict between the French and English monarchies throughout the medieval era. |

|||

The [[Anglo-Normans|Anglo-Norman]] [[House of Normandy|dynasty]] that had ruled [[Kingdom of England|England]] since the Norman conquest of 1066 was brought to an end when [[Henry II of England|Henry]], the son of [[Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou|Geoffrey of Anjou]] and [[Empress Matilda]], and great-grandson of [[William the Conqueror]], became the first of the [[Angevin kings of England]] in 1154 as Henry II.{{Sfn|Bartlett|2000|p=22}} The Angevin kings ruled over what was later known as the [[Angevin Empire]], which included more French territory than that under the [[List of French monarchs|kings of France]]. The Angevins still owed [[Homage (feudal)|homage]] to the French king for these territories. From the 11th century, the Angevins had autonomy within their French domains, neutralizing the issue.{{Sfn|Bartlett|2000|p=17}} |

|||

[[John, King of England|King John of England]] inherited the Angevin domains from his brother [[Richard I of England|Richard I]]. However, [[Philip II of France]] acted decisively to exploit the weaknesses of John, both legally and militarily, and [[French invasion of Normandy (1202–1204)|by 1204 had succeeded in taking control of much of the Angevin continental possessions]]. Following John's reign, the [[Battle of Bouvines]] (1214), the [[Saintonge War]] (1242), and finally the [[War of Saint-Sardos]] (1324), the English king's holdings on the continent, as [[Duke of Aquitaine]], were limited roughly to provinces in Gascony.{{Sfn|Gormley|2007}} |

|||

The dispute over Guyenne is even more important than the dynastic question in explaining the outbreak of the war. Guyenne posed a significant problem to the kings of France and England: Edward III was a vassal of Philip VI of France because of his French possessions and was required to recognize the [[suzerainty]] of the King of France over them. In practical terms, a judgment in Guyenne might be subject to an appeal to the French royal court. The King of France had the power to revoke all legal decisions made by the King of England in Aquitaine, which was unacceptable to the English. Therefore, sovereignty over Guyenne was a latent conflict between the two monarchies for several generations. |

|||

During the War of Saint-Sardos, [[Charles, Count of Valois|Charles of Valois]], father of Philip VI, invaded Aquitaine on behalf of Charles IV and conquered the duchy after a local insurrection, which the French believed had been incited by [[Edward II of England]]. Charles IV grudgingly agreed to return this territory in 1325. Edward II had to compromise to recover his duchy: he sent his son, the future [[Edward III of England|Edward III]], to pay homage. |

|||

The King of France agreed to restore Guyenne, minus [[Agenais|Agen]], but the French delayed the return of the lands, which helped Philip VI. On 6 June 1329, Edward III finally paid homage to the King of France. However, at the ceremony, Philip VI had it recorded that the homage was not due to the fiefs detached from the duchy of Guyenne by Charles IV (especially Agen). For Edward, the homage did not imply the renunciation of his claim to the extorted lands. |

|||

=== Gascony under the King of England === |

|||

[[File:Guyenne 1328-en.svg|thumb|France in 1330. |

|||

{{Legend|#809bd8|France before 1214}} |

|||

{{Legend|#837bca|French acquisitions until 1330}} |

|||

{{Legend|#eb8c9e|England and Guyenne/Gascony as of 1330}} |

|||

]] |

|||

In the 11th century, [[Gascony]] in southwest France had been incorporated into Aquitaine (also known as ''Guyenne'' or ''Guienne'') and formed with it the province of Guyenne and Gascony (French: ''Guyenne-et-Gascogne''). The [[Angevin kings of England]] became [[dukes of Aquitaine]] after [[Henry II of England|Henry II]] married the former Queen of France, [[Eleanor of Aquitaine]], in 1152, from which point the lands were held in vassalage to the French crown. By the 13th century the terms ''Aquitaine'', ''Guyenne'' and ''Gascony'' were virtually synonymous.<ref>{{Harvnb|Harris|1994|p=8}}; {{Harvnb|Prestwich|1988|p=298}}.</ref> |

|||

At the beginning of Edward III's reign on 1 February 1327, the only part of Aquitaine that remained in his hands was the Duchy of Gascony. The term ''Gascony'' came to be used for the territory held by the Angevin ([[Plantagenet]]) kings of England in southwest France, although they still used the title Duke of Aquitaine.<ref>{{Harvnb|Prestwich|1988|p=298}}; {{Harvnb|Prestwich|2007|pp=292–293}}.</ref> |

|||

For the first 10 years of Edward III's reign, Gascony had been a significant friction point. The English argued that, as Charles IV had not acted properly towards his tenant, Edward should be able to hold the duchy free of French [[suzerainty]]. The French rejected this argument, so in 1329, the 17-year-old Edward III paid homage to Philip VI. Tradition demanded that vassals approach their liege unarmed, with heads bare. Edward protested by attending the ceremony wearing his crown and sword.{{Sfn|Wilson|2011|p=194}} Even after this pledge of homage, the French continued to pressure the English administration.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|p=394}} |

|||

Gascony was not the only sore point. One of Edward's influential advisers was [[Robert III of Artois]]. Robert was an exile from the French court, having fallen out with Philip VI over an inheritance claim. He urged Edward to start a war to reclaim France, and was able to provide extensive intelligence on the French court.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|p=306}} |

|||

=== Franco-Scot alliance === |

|||

{{See also|Auld Alliance}} |

|||

France was an ally of the [[Kingdom of Scotland]] as English kings had tried to subjugate the country for some time. In 1295, [[Auld Alliance|a treaty]] was signed between France and Scotland during the reign of [[Philip IV of France|Philip the Fair]], known as the Auld Alliance. Charles IV formally [[Treaty of Corbeil (1326)|renewed the treaty]] in 1326, promising Scotland that France would support the Scots if England invaded their country. Similarly, France would have Scotland's support if its own kingdom were attacked. Edward could not succeed in his plans for Scotland if the Scots could count on French support.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|pp=304–305}} |

|||

Philip VI had assembled a large naval fleet off Marseilles as part of an ambitious plan for a [[crusade]] to the [[Holy Land]]. However, the plan was abandoned and the fleet, including elements of the Scottish navy, moved to the [[English Channel]] off Normandy in 1336, threatening England.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|p=306}} To deal with this crisis, Edward proposed that the English raise two armies, one to deal with the Scots "at a suitable time" and the other to proceed at once to Gascony. At the same time, ambassadors were to be sent to France with a proposed treaty for the French king.{{Sfn|Sumption|1999|p=180}} |

|||

== Beginning of the war: 1337–1360 == |

|||

{{Main|Hundred Years' War, 1337–1360}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Edwardian War}} |

{{Campaignbox Edwardian War}} |

||

[[File:Hundred years war.gif|thumb|200px|right|Animated map showing progress of the war (territorial changes and the most important battles between 1337 and 1453).]] |

|||

{{Main|Hundred Years' War (1337–1360)}} |

|||

{{Seealso|War of the Breton Succession}} |

|||

=== End of homage === |

|||

Open hostilities broke out as French ships began scouting coastal settlements on the [[English Channel]] and in 1337 Philip reclaimed the Gascon fief, citing feudal law and saying that Edward had broken his oath (a [[felony]]) by not attending to the needs and demands of his lord. Edward III responded by saying he was in fact the rightful heir to the French throne, and on [[All Saints' Day]], [[Henry Burghersh]], [[Bishop of Lincoln]], arrived in [[Paris]] with the defiance of the king of England. War had been declared. |

|||

At the end of April 1337, Philip of France was invited to meet the delegation from England but refused. The ''[[arrière-ban]]'', a call to arms, was proclaimed throughout France starting on 30 April 1337. Then, in May 1337, Philip met with his Great Council in Paris. It was agreed that the Duchy of Aquitaine, effectively Gascony, should be taken back into the King's hands because Edward III was in breach of his obligations as a vassal and had sheltered the King's "mortal enemy" [[Robert III of Artois|Robert d'Artois]].{{Sfn|Sumption|1999|p=184}} Edward responded to the confiscation of Aquitaine by challenging Philip's right to the French throne. |

|||

When Charles IV died, Edward claimed the succession of the French throne through the right of his mother, Isabella (Charles IV's sister), daughter of Philip IV. His claim was considered invalidated by Edward's homage to Philip VI in 1329. Edward revived his claim and in 1340 formally assumed the title "King of France and the French Royal Arms".{{Sfn|Prestwich|2003|pp=149–150}} |

|||

[[Image:BattleofSluys.jpeg|thumb|left|Battle of Sluys from a [[Froissart of Louis of Gruuthuse (BnF Fr 2643-6)|manuscript]] of [[Froissart's Chronicles]], Bruge, c.1470]] |

|||

On 26 January 1340, Edward III formally received homage from Guy, half-brother of the [[Count of Flanders]]. The civic authorities of [[Ghent]], [[Ypres]], and [[Bruges]] proclaimed Edward King of France. Edward aimed to strengthen his alliances with the [[Low Countries]]. His supporters could claim that they were loyal to the "true" King of France and did not rebel against Philip. In February 1340, Edward returned to England to try to raise more funds and also deal with political difficulties.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|pp=307–312}} |

|||

In the early years of the war, Edward III allied with the nobles of the [[Low Countries]] and the burghers of [[Flanders]], but after two campaigns where nothing was achieved, the alliance fell apart in 1340. The payments of subsidies to the German princes and the costs of maintaining an army abroad dragged the English government into bankruptcy, heavily damaging Edward’s prestige. At sea, France enjoyed supremacy for some time, through the use of Genoese ships and crews. Several towns on the English coast were sacked, some repeatedly. This caused fear and disruption along the English coast. There was a constant fear during this part of the war that the French would invade. France's sea power led to economic disruptions in England as it cut down on the wool trade to Flanders and the wine trade from Gascony. However, in 1340, while attempting to hinder the English army from landing, the French fleet was almost completely destroyed in the [[Battle of Sluys]]. After this, England was able to dominate the [[English Channel]] for the rest of the war, preventing French [[invasions]]. |

|||

Relations with Flanders were also tied to the [[Medieval English wool trade|English wool trade]] since Flanders' principal cities relied heavily on textile production, and England supplied much of the raw material they needed. Edward III had commanded that his [[Lord Chancellor|chancellor]] sit on the [[woolsack]] in council as a symbol of the pre-eminence of the wool trade.{{Sfn|Friar|2004|pp=480–481}} At the time there were about 110,000 [[History of Sussex#Wool|sheep in Sussex]] alone.<ref name="darby160">{{Cite book |first=R.E. |last=Glassock |title=England circa 1334|page=160}} ''in'' {{Harvnb|Darby|1976}}.</ref> The great medieval English monasteries produced large wool surpluses sold to mainland Europe. Successive governments were able to make large amounts of money by taxing it.{{Sfn|Friar|2004|pp=480–481}} France's sea power led to economic disruptions for England, shrinking the wool trade to [[County of Flanders|Flanders]] and the wine trade from Gascony.<ref>{{Harvnb|Sumption|1999|pp=188–189}}; {{Harvnb|Sumption|1999|pp=233–234}}.</ref> |

|||

In 1341, conflict over the succession to the Duchy of [[Brittany]] began the [[Breton War of Succession]], in which Edward backed [[John IV, Duke of Brittany|John of Montfort]] and Philip backed [[Charles, Duke of Brittany|Charles of Blois]]. Action for the next few years focused around a back and forth struggle in Brittany, with the city of [[Vannes]] changing hands several times, as well as further campaigns in Gascony with mixed success for both sides. |

|||

=== Outbreak, the English Channel and Brittany === |

|||

In July 1346, Edward mounted a major invasion across the Channel, landing in the [[Cotentin]]. The English army captured [[Caen]] in just one day, surprising the French who had expected the city to hold out much longer. Philip gathered a large army to oppose him, and Edward chose to march northward toward the Low Countries, pillaging as he went, rather than attempting to take and hold territory. Finding himself unable to outmanoeuvre Philip, Edward positioned his forces for battle, and Philip's army attacked. The famous [[Battle of Crécy]] was a complete disaster for the French, largely credited to the [[English longbow]]men. Edward proceeded north unopposed and besieged the city of [[Calais]] on the [[English Channel]], capturing it in 1347. This became an important strategic asset for the English. It allowed them to keep troops in France safely. In the same year, an English victory against Scotland in the [[Battle of Neville's Cross]] led to the capture of David II and greatly reduced the threat from Scotland. |

|||

[[File:BattleofSluys.jpeg|thumb|upright=1.3|The [[Battle of Sluys]] from a [[Bibliothèque nationale de France|BNF]] [[Froissart of Louis of Gruuthuse (BnF Fr 2643-6)|manuscript]] of [[Froissart's Chronicles]], Bruges, {{Circa|1470}}.]] |

|||

On 22 June 1340, Edward and his fleet sailed from England and arrived off the [[Zwin]] estuary the next day. The French fleet assumed a defensive formation off the port of [[Sluis]]. The English fleet deceived the French into believing they were withdrawing. When the wind turned in the late afternoon, the English attacked with the wind and sun behind them. The French fleet was almost destroyed in what became known as the [[Battle of Sluys]]. |

|||

In 1348, the [[Black Death]] began to ravage Europe. In 1356, after it had passed and England was able to recover financially, Edward's son and namesake, the [[Prince of Wales]], known as the [[Edward, the Black Prince|Black Prince]], invaded France from Gascony, winning a great victory in the [[Battle of Poitiers (1356)|Battle of Poitiers]], where the English archers repeated the tactics used at Crécy. The new French king, [[John II of France|John II]], was captured (''See: [[Ransom of King John II of France]].'') John signed a truce with Edward, and in his absence, much of the government began to collapse. Later that year, the [[Second Treaty of London]] was signed, by which England gained possession of [[Aquitaine]] and John was freed. |

|||

England dominated the English Channel for the rest of the war, preventing French [[invasions]].{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|pp=307–312}} At this point, Edward's funds ran out and the war probably would have ended were it not for the death of the [[John III, Duke of Brittany|Duke of Brittany]] in 1341 precipitating a succession dispute between the duke's half-brother [[John of Montfort]] and [[Charles I, Duke of Brittany|Charles of Blois]], nephew of Philip VI.{{Sfn|Rogers|2010|pp=88–89}} |

|||

The French countryside at this point began to fall into complete chaos. [[Brigandage]], the actions of the professional soldiery when fighting was at low ebb, was rampant. In 1358, the peasants rose in rebellion in what was called the [[Jacquerie]]. Edward invaded France, for the third and last time, hoping to capitalise on the discontent and seize the throne, but although no French army stood against him in the field, he was unable to take [[Paris]] or [[Rheims]] from the [[Dauphin of France|Dauphin]], later [[Charles V of France|King Charles V]]. He negotiated the [[Treaty of Brétigny]] which was signed in 1360. The English came out of this phase of the war with half of Brittany, Aquitaine (about a quarter of France), Calais, Ponthieu, and about half of France's vassal states as their allies, representing the clear advantage of a united England against a generally disunified France. |

|||

In 1341, this inheritance dispute over the [[Duchy of Brittany]] set off the [[War of the Breton Succession]], in which Edward backed John of Montfort and Philip backed Charles of Blois. Action for the next few years focused on a back-and-forth struggle in Brittany. The city of [[Vannes]] in Brittany changed hands several times, while further campaigns in Gascony met with mixed success for both sides.{{Sfn|Rogers|2010|pp=88–89}} The English-backed Montfort finally took the duchy but not until 1364.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Auray#ref783089 |title=Auray, France |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |language=en |access-date=2018-04-14 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180415064637/https://www.britannica.com/place/Auray#ref783089 |archive-date=15 April 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==First peace: 1360–1369== |

|||

{{Main|Treaty of Brétigny}} |

|||

{{Seealso|Castilian Civil War}} |

|||

=== Battle of Crécy and the taking of Calais === |

|||

When John's son [[Louis I of Anjou|Louis I, Duc d'Anjou]], sent to the English as a hostage on John's behalf, escaped in 1362, John II chivalrously gave himself up and returned to captivity in England. He died in honourable captivity in 1364 and [[Charles V of France|Charles V]] succeeded him as king of France. |

|||

[[File:Crécy - Grandes Chroniques de France.jpg|thumb|upright=1.2|left|[[Battle of Crécy]], 1346, from the [[Grandes Chroniques de France]]. [[British Library]], London]] |

|||

{{See also|Hundred Years' War, 1345–1347}} |

|||

In July 1346, Edward mounted a major invasion across the channel, landing on Normandy's [[Cotentin Peninsula]] at [[Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue|St Vaast]]. The English army [[Battle of Caen (1346)|captured]] the city of [[Caen]] in just one day, surprising the French. Philip mustered a large army to oppose Edward, who chose to march northward toward the Low Countries, pillaging as he went. He reached the river Seine to find most of the crossings destroyed. He moved further south, worryingly close to Paris until he found the crossing at Poissy. This had only been partially destroyed, so the carpenters within his army were able to fix it. He then continued to Flanders until he reached the river Somme. The army crossed at a tidal ford at Blanchetaque, stranding Philip's army. Edward, assisted by this head start, continued on his way to Flanders once more until, finding himself unable to outmaneuver Philip, Edward positioned his forces for battle, and Philip's army attacked. |

|||

[[File:Edward III counting the dead on the battlefield of Crécy.jpg|thumb|upright=1.2|[[Edward III]] counting the dead on the battlefield of Crécy]] |

|||

The Treaty of Brétigny had made Edward renounce his claim to the French crown. At the same time it greatly expanded his territory in Aquitaine and confirmed his conquest of Calais. In reality, Edward never renounced his claim to the French crown, and Charles made a point of retaking Edward's new territory as soon as he ascended to the throne. In 1369, on the pretext that Edward III had failed to observe the terms of the treaty of Brétigny, Charles declared war once again. |

|||

The [[Battle of Crécy]] of 1346 was a complete disaster for the French, largely credited to the English [[English longbow|longbowmen]] and the French king, who allowed his army to attack before it was ready.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|pp=318–319}} Philip appealed to his Scottish allies to help with a diversionary attack on England. King [[David II of Scotland]] responded by invading northern England, but his army was defeated, and he was captured at the [[Battle of Neville's Cross]] on 17 October 1346. This greatly reduced the threat from Scotland.{{Sfn|Rogers|2010|pp=88–89}}{{Sfn|Rogers|2010|pp=55–45}} |

|||

==French ascendancy under Charles V: 1369–1389== |

|||

In France, Edward proceeded north unopposed and [[Siege of Calais (1346–1347)|besieged the city]] of [[Calais]] on the English Channel, capturing it in 1347. This became an important strategic asset for the English, allowing them to keep troops safely in northern France.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|pp=318–319}} Calais would remain under English control, even after the end of the Hundred Years' War, until the successful [[Siege of Calais (1558)|French siege in 1558]].{{Sfn|Grummitt|2008|p=1}} |

|||

=== Battle of Poitiers === |

|||

{{Main|Battle of Poitiers}} |

|||

The [[Black Death]], which had just arrived in Paris in 1348, ravaged Europe.<ref>''The Black Death'', transl. & ed. Rosemay Horrox, (Manchester University Press, 1994), 9.</ref> In 1355, after the plague had passed and England was able to recover financially,{{Sfn|Hewitt|2004|p=1}} King Edward's son and namesake, the [[Prince of Wales]], later known as the [[Edward, the Black Prince|Black Prince]], led a [[Black Prince's chevauchée of 1355|Chevauchée]] from Gascony into France, during which he pillaged [[Avignonet]], [[Castelnaudary]], [[Carcassonne]], and [[Narbonne]]. The next year during [[Black Prince's chevauchée of 1356|another Chevauchée]] he ravaged [[Auvergne]], [[Limousin]], and [[Berry, France|Berry]] but failed to take [[Bourges]]. He offered terms of peace to King [[John II of France]] (known as John the Good), who had outflanked him near Poitiers but refused to surrender himself as the price of their acceptance. |

|||

This led to the [[Battle of Poitiers]] (19 September 1356) where the Black Prince's army routed the French.{{Sfn|Hunt|1903|p=388}} During the battle, the Gascon noble [[Jean III de Grailly, captal de Buch|Jean de Grailly]], [[captal de Buch]] led a mounted unit that was concealed in a forest. The French advance was contained, at which point de Grailly led a flanking movement with his horsemen, cutting off the French retreat and successfully capturing King John and many of his nobles.<ref>{{Harvnb|Le Patourel|1984|pp=20–21}}; {{Harvnb|Wilson|2011|p=218}}.</ref> With John held hostage, his son the [[Dauphin of France|Dauphin]] (later to become [[Charles V of France|Charles V]]) assumed the powers of the king as [[Regency (government)|regent]].{{Sfn|Guignebert|1930|loc=Volume 1. pp. 304–307}} |

|||

After the Battle of Poitiers, many French nobles and mercenaries rampaged, and chaos ruled. A contemporary report recounted: |

|||

{{Blockquote|... all went ill with the kingdom and the State was undone. Thieves and robbers rose up everywhere in the land. The Nobles despised and hated all others and took no thought for usefulness and profit of lord and men. They subjected and despoiled the peasants and the men of the villages. In no wise did they defend their country from its enemies; rather did they trample it underfoot, robbing and pillaging the peasants' goods ...|From the ''Chronicles of [[Jean de Venette]]''{{Sfn|Venette|1953|p=66}}}} |

|||

=== Reims campaign and Black Monday === |

|||

{{Main|Reims campaign}} |

|||

[[File:Black Monday hailstorm.jpg|thumb|upright=1.1|A later engraving of [[Black Monday (1360)|Black Monday]] in 1360: hailstorms and lightning ravage the English army outside [[Chartres]]]] |

|||

Edward invaded France, for the third and last time, hoping to capitalise on the discontent and seize the throne. The Dauphin's strategy was that of non-engagement with the English army in the field. However, Edward wanted the crown and chose the cathedral city of [[Reims]] for his coronation (Reims was the traditional coronation city).{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|p=326}} However, the citizens of Reims built and reinforced the city's defences before Edward and his army arrived.{{Sfn|Le Patourel|1984|p=189}} Edward besieged the city for five weeks, but the defences held and there was no coronation.{{Sfn|Prestwich|2007|p=326}} Edward moved on to Paris, but retreated after a few skirmishes in the suburbs. Next was the town of [[Chartres]]. |

|||

Disaster struck in a freak [[hailstorm]] on the encamped army, causing over 1,000 English deaths – the so-called [[Black Monday (1360)|Black Monday]] at Easter 1360. This devastated Edward's army and forced him to negotiate when approached by the French.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Apr 13, 1360: Hail kills English troops |url=http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/hail-kills-english-troops |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120905150026/http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/hail-kills-english-troops |archive-date=5 September 2012 |access-date=2016-01-22 |website=[[History (U.S. TV network)|History.com]]}}</ref> A conference was held at Brétigny that resulted in the [[Treaty of Brétigny]] (8 May 1360).{{Sfn|Le Patourel|1984|p=32}} The treaty was ratified at Calais in October. In return for increased lands in Aquitaine, Edward renounced Normandy, Touraine, Anjou and Maine and consented to reduce King John's ransom by a million crowns. Edward also abandoned his claim to the crown of France.<ref>{{Harvnb|Guignebert|1930|loc=Volume 1. pp. 304–307}}; {{Harvnb|Le Patourel|1984|pp=20–21}}; {{Harvnb|Chisholm|1911|p=501}}</ref> |

|||

== First peace: 1360–1369 == |

|||

[[File:Map- France at the Treaty of Bretigny.jpg|thumb|France at the [[Treaty of Brétigny]], English holdings in light red]] |

|||

The French king, [[John II of France|John II]], was held captive in England for four years. The [[Treaty of Brétigny]] set his ransom at 3 million crowns and allowed for hostages to be held in lieu of John. The hostages included two of his sons, several princes and nobles, four inhabitants of Paris, and two citizens from each of the nineteen principal towns of France. While these hostages were held, John returned to France to try to raise funds to pay the ransom. In 1362, John's son [[Louis I of Anjou|Louis of Anjou]], a hostage in English-held Calais, escaped captivity. With his stand-in hostage gone, John felt honour-bound to return to captivity in England.{{Sfn|Guignebert|1930|loc=Volume 1. pp. 304–307}}{{Sfn|Chisholm|1911|p=501}} |

|||

The French crown had been at odds with [[Kingdom of Navarre|Navarre]] (near southern [[Gascony]]) since 1354, and in 1363, the Navarrese used the captivity of John II in London and the political weakness of the Dauphin to try to seize power.{{Sfn|Wagner|2006|pp=102–103}} Although there was no formal treaty, Edward III supported the Navarrese moves, particularly as there was a prospect that he might gain control over the northern and western provinces as a consequence. With this in mind, Edward deliberately slowed the peace negotiations.{{Sfn|Ormrod|2001|p=384}} In 1364, John II died in London, while still in honourable captivity.<ref name="Backman179">{{Harvnb|Backman|2003|pp=179–180}} – Nobles captured in battle were held in "Honorable Captivity", which recognised their status as prisoners of war and permitted ransom.</ref> [[Charles V of France|Charles V]] succeeded him as king of France.{{Sfn|Guignebert|1930|loc=Volume 1. pp. 304–307}}<ref name="britannica1">Britannica. [https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/78946/Treaty-of-Bretigny Treaty of Brétigny] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101145830/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/78946/Treaty-of-Bretigny |date=1 November 2012}}. Retrieved 21 September 2012</ref> On 16 May, one month after the dauphin's accession and three days before his coronation as Charles V, the Navarrese suffered a crushing defeat at the [[Battle of Cocherel]].{{Sfn|Wagner|2006|p=86}} |

|||

== French ascendancy under Charles V: 1369–1389 == |

|||

=== Aquitaine and Castile === |

|||

{{Main|Hundred Years' War, 1369–1389}} |

|||

{{See also|Castilian Civil War}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Caroline War}} |

{{Campaignbox Caroline War}} |

||

In 1366, there was a civil war of succession in [[Crown of Castile#Ascension of the Trastámara dynasty|Castile]] (part of modern Spain). The forces of the ruler [[Peter of Castile]] were pitched against those of his half-brother [[Henry II of Castile|Henry of Trastámara]]. The English crown supported Peter; the French supported Henry. French forces were led by [[Bertrand du Guesclin]], a Breton, who rose from relatively humble beginnings to prominence as one of France's war leaders. Charles V provided a force of 12,000, with du Guesclin at their head, to support Trastámara in his invasion of Castile.{{Sfn|Curry|2002|pp=69–70}} |

|||

{{Main|Hundred Years' War (1369–1389)}} |

|||

[[File:Du Guesclin Dinan.jpg|thumb|Statue of [[Bertrand du Guesclin]] in [[Dinan]], [[Brittany]]]] |

|||

The reign of Charles V saw the English steadily pushed back. Although the Breton war ended in favour of the English at the [[Battle of Auray]], the dukes of Brittany eventually reconciled with the French throne. The Breton soldier [[Bertrand du Guesclin]] became one of the most successful French generals of the Hundred Years' War. |

|||

[[Image:Du Guesclin Dinan.jpg|thumb|Statue of Du Guesclin in [[Dinan]]]] |

|||

Peter appealed to England and Aquitaine's [[Edward the Black Prince|Black Prince]], Edward of Woodstock, for help, but none was forthcoming, forcing Peter into exile in Aquitaine. The Black Prince had previously agreed to support Peter's claims but concerns over the terms of the treaty of Brétigny led him to assist Peter as a representative of Aquitaine, rather than England. He then led an Anglo-Gascon army into Castile. Peter was restored to power after Trastámara's army was defeated at the [[Battle of Nájera]].{{Sfn|Wagner|2006|p=78}} |

|||

Simultaneously, the Black Prince was occupied with war in the [[Iberian peninsula]] from 1366 and due to illness was relieved of command in 1371, whilst Edward III was too elderly to fight; providing France with even more advantages. [[Pedro of Castile]], whose daughters Constance and Isabella were married to the Black Prince's brothers [[John of Gaunt]] and [[Edmund of Langley]], was deposed by [[Henry II of Castile|Henry of Trastámara]] in 1370 with the support of Du Guesclin and the French. War erupted between Castile and France on one side and Portugal and England on the other. |

|||

Although the Castilians had agreed to fund the Black Prince, they failed to do so. The Prince was suffering from ill health and returned with his army to Aquitaine. To pay off debts incurred during the Castile campaign, the prince instituted a [[hearth tax]]. [[Arnaud Amanieu, Lord of Albret|Arnaud-Amanieu VIII]], Lord of [[Albret]] had fought on the Black Prince's side during the war. Albret, who already had become discontented by the influx of English administrators into the enlarged Aquitaine, refused to allow the tax to be collected in his fief. He then joined a group of Gascon lords who appealed to Charles V for support in their refusal to pay the tax. Charles V summoned one Gascon lord and the Black Prince to hear the case in his High Court in Paris. The Black Prince answered that he would go to Paris with sixty thousand men behind him. War broke out again and Edward III resumed the title of King of France.{{Sfn|Wagner|2006|p=122}} Charles V declared that all the English possessions in France were forfeited, and before the end of 1369 all of Aquitaine was in full revolt.<ref>{{Harvnb|Wagner|2006|p=122}}; {{Harvnb|Wagner|2006|pp=3–4}}.</ref> |

|||

With the death of [[John Chandos]], [[seneschal]] of [[Poitou]], in the field and the capture of the [[Captal de Buch]], the English were deprived of some of their best generals in France. Du Guesclin, in a series of careful [[Fabian Strategy|Fabian]] campaigns, avoiding major English field armies, captured many towns, including [[Poitiers]] in 1372 and [[Bergerac, Dordogne|Bergerac]] in 1377. The English response to Du Guesclin was to launch a series of destructive ''[[chevauchée]]s''. But Du Guesclin refused to be drawn in by them. |

|||

With the Black Prince gone from Castile, Henry of Trastámara led a second invasion that ended with Peter's death at the [[Battle of Montiel]] in March 1369. The new Castilian regime provided naval support to French campaigns against Aquitaine and England.{{Sfn|Wagner|2006|p=78}} In 1372, the Castilian fleet defeated the English fleet in the [[Battle of La Rochelle]]. |

|||

With the death of the Black Prince in 1376 and Edward III in 1377, the prince's underaged son [[Richard II of England|Richard of Bordeaux]] succeeded to the English throne. Then, with Du Guesclin's death in 1380, and the continued threat to England's northern borders from Scotland represented by the [[Battle of Otterburn]], the war inevitably wound down with the [[Truce of Leulingham]] in 1389. The peace was extended many times before open war flared up again. |

|||

=== 1373 campaign of John of Gaunt === |

|||

==Second peace: 1389–1415== |

|||

{{Main|John of Gaunt's chevauchée of 1373}} |

|||

{{Seealso|Civil war between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians}} |

|||

In August 1373, [[John of Gaunt]], accompanied by [[John IV, Duke of Brittany|John de Montfort]], Duke of Brittany led a force of 9,000 men from Calais on a {{Lang|fr|chevauchée}}. While initially successful as French forces were insufficiently concentrated to oppose them, the English met more resistance as they moved south. French forces began to concentrate around the English force but under orders from [[Charles V of France|Charles V]], the French avoided a set battle. Instead, they fell on forces detached from the main body to raid or forage. The French shadowed the English and in October, the English found themselves trapped against the [[Allier (river)|River Allier]] by four French forces. With some difficulty, the English crossed at the bridge at [[Moulins, Allier|Moulins]] but lost all their baggage and loot. The English carried on south across the [[Limousin]] plateau but the weather was turning severe. Men and horses died in great numbers and many soldiers, forced to march on foot, discarded their armour. At the beginning of December, the English army entered friendly territory in [[Gascony]]. By the end of December, they were in [[Bordeaux]], starving, ill-equipped, and having lost over half of the 30,000 horses with which they had left Calais. Although the march across France had been a remarkable feat, it was a military failure.{{Sfn|Sumption|2012|pp=187–196}} |

|||

Although [[Henry IV of England]] planned campaigns in France, he was unable to put them into effect due to his short reign. In the meantime, though, the French King [[Charles VI of France|Charles VI]] was descending into madness, and an open conflict for power began between his cousin, [[John the Fearless]], and his brother, [[Louis of Valois, Duke of Orléans|Louis of Orléans]]. After Louis's assassination, the [[Armagnac (party)|Armagnac]] family took political power in opposition to John. By 1410, both sides were bidding for the help of English forces in a civil war. |

|||

=== English turmoil === |

|||

England too was plagued with internal strife during this period, as [[List of revolutions and rebellions|uprisings]] in [[Ireland]] and [[Wales]] were accompanied by renewed border war with Scotland and two separate civil wars. The Irish troubles embroiled much of the reign of [[Richard II of England|Richard II]], who had not resolved them by the time he lost his throne and life to his cousin Henry, who took power for himself in 1399. This was followed by the rebellion of [[Owain Glyndŵr]] in Wales which was not finally put down until 1415 and actually resulted in Welsh semi-independence for a number of years. In Scotland, the change in regime in England prompted a fresh series of border raids which were countered by an invasion in 1402 and the defeat of a Scottish army at the [[Battle of Homildon Hill]]. A dispute over the spoils of this action between Henry and the [[Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland|Earl of Northumberland]] resulted in a long and bloody struggle between the two for control of northern England, which was only resolved with the almost complete destruction of the Percy family by 1408. Throughout this period, England was also faced with repeated raids by French and Scandinavian [[pirates]], which heavily damaged trade and the navy. These problems accordingly delayed any resurgence of the dispute with France until 1415. |

|||

[[File:Ofensivas Tovar-Vienne contra Inglaterra 01.jpg|thumb|The Franco-Castilian Navy, led by Admirals |

|||

[[Jean de Vienne|de Vienne]] and [[Fernando Sánchez de Tovar|Tovar]], managed to raid the English coasts for the first time since the beginning of the Hundred Years' War.]] |

|||

With his health deteriorating, the Black Prince returned to England in January 1371, where his father Edward III was elderly and also in poor health. The prince's illness was debilitating, and he died on 8 June 1376.{{Sfn|Barber|2004}} Edward III died the following year on 21 June 1377{{Sfn|Ormrod|2008}} and was succeeded by the Black Prince's second son [[Richard II of England|Richard II]] who was still a child of 10 ([[Edward of Angoulême]], the Black Prince's first son, had died sometime earlier).{{Sfn|Tuck|2004}} The treaty of Brétigny had left Edward III and England with enlarged holdings in France, but a small professional French army under the leadership of du Guesclin pushed the English back; by the time Charles V died in 1380, the English held only Calais and a few other ports.<ref name="vauchez283">Francoise Autrand. Charles V King of France ''in'' {{Harvnb|Vauchéz|2000|pp=283–284}}</ref> |

|||

It was usual to appoint a [[regent]] in the case of a child monarch but no regent was appointed for Richard II, who nominally exercised the power of kingship from the date of his accession in 1377.{{Sfn|Tuck|2004}} Between 1377 and 1380, actual power was in the hands of a series of councils. The political community preferred this to a regency led by the king's uncle, [[John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster|John of Gaunt]], although Gaunt remained highly influential.{{Sfn|Tuck|2004}} Richard faced many challenges during his reign, including the [[Peasants' Revolt]] led by [[Wat Tyler]] in 1381 and an Anglo-Scottish war in 1384–1385. His attempts to raise taxes to pay for his Scottish adventure and for the protection of Calais against the French made him increasingly unpopular.{{Sfn|Tuck|2004}} |

|||

==Resumption of the war under Henry V: 1415–1429== |

|||

==== 1380 campaign of the Earl of Buckingham ==== |

|||

In July 1380, the [[Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester|Earl of Buckingham]] commanded an expedition to France to aid England's ally, the [[John IV, Duke of Brittany|Duke of Brittany]]. The French refused battle before the walls of [[Troyes]] on 25 August; Buckingham's forces continued their {{Lang|fr|chevauchée}} and in November laid siege to [[Nantes]].{{Sfn|Sumption|2012|pp=385–390, 396–399}} The support expected from the Duke of Brittany did not appear and in the face of severe losses in men and horses, Buckingham was forced to abandon the siege in January 1381.{{Sfn|Sumption|2012|p=409}} In February, reconciled to the regime of the new French king [[Charles VI of France|Charles VI]] by the [[Treaty of Guérande (1381)|Treaty of Guérande]], Brittany paid 50,000 francs to Buckingham for him to abandon the siege and the campaign.{{Sfn|Sumption|2012|p=411}} |

|||

=== French turmoil === |

|||

After the deaths of Charles V and du Guesclin in 1380, France lost its main leadership and overall momentum in the war. [[Charles VI of France|Charles VI]] succeeded his father as king of France at the age of 11, and he was thus put under a regency led by his uncles, who managed to maintain an effective grip on government affairs until about 1388, well after Charles had achieved royal majority. |

|||

With France facing widespread destruction, plague, and economic recession, high taxation put a heavy burden on the French peasantry and urban communities. The war effort against England largely depended on royal taxation, but the population was increasingly unwilling to pay for it, as would be demonstrated at the [[Harelle]] and Maillotin revolts in 1382. Charles V had abolished many of these taxes on his deathbed, but subsequent attempts to reinstate them stirred up hostility between the French government and populace. |

|||

Philip II of Burgundy, the uncle of the French king, brought together a Burgundian-French army and a fleet of 1,200 ships near the Zeeland town of [[Sluis]] in the summer and autumn of 1386 to attempt an invasion of England, but this venture failed. However, Philip's brother [[John, Duke of Berry|John of Berry]] appeared deliberately late, so that the autumn weather prevented the fleet from leaving and the invading army then dispersed again. |

|||

Difficulties in raising taxes and revenue hampered the ability of the French to fight the English. At this point, the war's pace had largely slowed down, and both nations found themselves fighting mainly through [[proxy war]]s, such as during the [[1383–1385 Portuguese interregnum]]. The independence party in the [[Kingdom of Portugal]], which was supported by the English, won against the supporters of the King of Castile's claim to the Portuguese throne, who in turn was backed by the French. |

|||

== Second peace: 1389–1415 == |

|||

{{See also|Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Owain Glyndŵr's Revolt}} |

|||

[[File:Apanages.svg|thumb|France in 1388, just before signing a truce. English territories are shown in red, French royal territories are dark blue, papal territories are orange, and French vassals have the other colours.]] |

|||