Spare Rib: Difference between revisions

Fixed typo: 'Mmagazine' to 'Magazine' |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: title, url. URLs might have been anonymized. Add: authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Jay8g | Linked from User:Jay8g/sandbox | #UCB_webform_linked 72/80 |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{other uses|Spare rib (disambiguation)}} |

{{other uses|Spare rib (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2020}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2020}} |

||

{{Infobox |

{{Infobox magazine |

||

| title = |

| title = |

||

| image_file = Spare Rib magazine cover Dec 1972.jpg <!-- FAIR USE of It Jan-Feb '69.jpg: see image description page at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Spare Rib magazine cover Dec 1972.jpg for rationale --> |

| image_file = Spare Rib magazine cover Dec 1972.jpg <!-- FAIR USE of It Jan-Feb '69.jpg: see image description page at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Spare Rib magazine cover Dec 1972.jpg for rationale --> |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| website = http://www.bl.uk/spare-rib (archive) |

| website = http://www.bl.uk/spare-rib (archive) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Spare Rib''''' was a [[Second-wave feminism|second-wave]] |

'''''Spare Rib''''' was a [[Second-wave feminism|second-wave feminist]] [[magazine]], founded in 1972 in the [[United Kingdom]], that emerged from the [[Counterculture of the 1960s|counterculture of the late 1960s]] as a consequence of meetings involving, among others, [[Rosie Boycott, Baroness Boycott|Rosie Boycott]] and [[Marsha Rowe]]. ''Spare Rib'' is now recognised as having shaped debates about [[Feminism in the United Kingdom|feminism in the UK]], and as such it was digitised by the [[British Library]] in 2015.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |title=About the Spare Rib Digitisation Project |url=https://www.bl.uk/spare-rib/about-the-project |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190414104426/https://www.bl.uk/spare-rib/about-the-project |archive-date=14 April 2019 |access-date= |website=The British Library |language=en}}</ref> The magazine contained new writing and creative contributions that challenged stereotypes and supported collective solutions that related to feminist issues. It was published between 1972 and 1993.<ref>{{cite news|title=A short history of the most radical DIY magazines|url=http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/30762/1/orlando-magazine-on-a-short-history-of-the-most-radical-diy-magazines|first=Philomena|last= Epps|date=18 April 2016|access-date=5 October 2016|work=Dazed}}</ref> The title derives from [[Eve#Creation|the Biblical reference to Eve]], the first woman, created from [[Adam]]'s rib. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The first issue of ''Spare Rib'' was published in June 1972.<ref name=grf/> It was distributed by Seymour Press to big chains including [[WHSmith|W. H. Smith]] and Menzies — although |

The first issue of ''Spare Rib'' was published in [[London]] in June 1972.<ref name=grf/><ref>{{Cite news |last1=Jordan |first1=Justine |last2=Boycott |first2=Rosie |last3=Rowe |first3=Marsha |date=2018-06-11 |title=How we made: Spare Rib magazine |url=https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/jun/11/how-we-made-spare-rib-magazine |access-date=2024-10-02 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> It was distributed by Seymour Press to big chains including [[WHSmith|W. H. Smith & Son]] and Menzies — although the former refused to stock issue 13, due to the use of an expletive on the issue's back cover. Selling at first around 20,000 copies a month, it was circulated more widely through women's groups and networks. From 1976, ''Spare Rib'' was distributed by [[Publications Distribution Cooperative]] to a network of [[Radical bookshops in the United Kingdom|radical]] and alternative bookshops. |

||

The magazine's purpose, as described in its editorial, was to investigate and present alternatives to the traditional [[Gender role|gendered roles]] of virgin, wife, or mother.<ref>{{Cite web |last= |date=2011-03-22 |title=Women's History Month: Spare Rib |url=https://womenshistorynetwork.org/womens-history-month-spare-rib/ |access-date=2024-10-02 |website=Women's History Network |language=en-GB}}</ref> |

|||

The name ''Spare Rib'' started as a joke referring to biblical Eve being fashioned out of |

The name ''Spare Rib'' started as a joke referring to biblical Eve being fashioned out of Adam's rib, implying that a woman had no independence from the beginning of time.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |last=Rowe |first=Marsha |date=28 May 2015 |title=The design of Spare Rib |url=https://www.creativereview.co.uk/the-design-of-spare-rib/ |access-date=18 January 2023 |work=Creative Review}}</ref> |

||

The ''Spare Rib'' |

The ''Spare Rib'' [[manifesto]] stated:<ref>{{Cite web |title=Facsimile of Spare Rib manifesto |url=http://www.bl.uk/collection-items/facsimile-of-spare-rib-manifesto |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160308171925/https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/facsimile-of-spare-rib-manifesto |archive-date=8 March 2016 |access-date= |work=The British Library}}</ref> |

||

{{ |

{{blockquote|The concept of Women's Liberation is widely misunderstood, feared and ridiculed. Many women remain isolated and unhappy. We want to publish Spare RIB to try to change this. We believe that women's liberation is of vital importance to women now and, intrinsically, to the future of our society. Spare RIB will reach out to all women, cutting across material, economic and class barriers, to approach them as individuals in their own right.}} |

||

Early articles were linked closely with left-leaning political theories of the time, especially [[anti-capitalism]] and the exploitation of women as consumers through fashion. |

Early articles were linked closely with [[Left-wing politics|left]]-leaning political theories of the time, especially [[anti-capitalism]] and the exploitation of women as consumers through fashion.{{Citation needed|date=October 2024}} |

||

As the [[women's movement]] evolved during the 1970s, the magazine became a |

As the [[Feminist movement|women's movement]] evolved during the 1970s, the magazine became a forum for debate among members of the different streams that emerged within the movement, such as [[socialist feminism]], [[radical feminism]], [[lesbian feminism]], [[liberal feminism]], and [[black feminism]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=O'Sullivan|first1=Sue|title=Feminists and Flourbombs |url=http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/F/flourbombs/essay.html|publisher=Channel 4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080916221109/http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/F/flourbombs/essay.html |archive-date=16 September 2008|url-status=dead}}</ref> ''Spare Rib'' included contributions from well-known international feminist writers, activists, and theorists, as well as stories about ordinary women in their own words. Subjects included the "liberating orgasm", "kitchen sink racism", [[Anorexia nervosa|anorexia]], and [[Female genital mutilation in the United Kingdom|female genital mutilation]]. The magazine reflected debates about how best to tackle issues such as sexuality and racism.<ref name=":0Davies," /> |

||

Due to falling subscriptions and low advertising revenue, ''Spare Rib'' ceased publication in 1993.<ref name="grf">{{cite web|title=Spare Rib (Magazine, 1972-1993)|url=http://www.grassrootsfeminism.net/cms/node/234|work=Grassroots Feminism|access-date=10 August 2015|date=7 August 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author1-last= |author1-first= |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hLPJBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA56 |title=Feminist Media: Participatory Spaces, Networks and Cultural Citizenship |author2= |date=30 April 2014 |publisher=Transcript Verlag |isbn=978-3-8394-2157-4 |editor-last=Zobl |editor-first=Elke |series=Critical Studies in Media and Communication |volume=9 |page=56 |access-date=27 October 2015 |editor-last2=Drüeke |editor-first2=Ricarda}}</ref> |

|||

== Editors == |

== Editors == |

||

[[File:Spare-rib-manifesto.jpg|thumb|The ''Spare Rib'' manifesto.]] |

|||

[[File:Spare-rib-manifesto.jpg|thumb|The founders of ''Spare Rib'' set out to set the record straight on Women's Liberation. They sought to reach out to all women and in their manifesto they explain what was wrong with contemporary women's magazines and how their alternative would offer realistic solutions to the problems experienced by women.]] |

|||

''Spare Rib'' became a collective by the end of 1973 |

''Spare Rib'' became a [[collective]] by the end of 1973.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rowe |first=Marsha |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4VYqAAAAYAAJ&q=collective |title=Spare Rib Reader |date=1982 |publisher=Penguin Books |isbn=978-0-14-005250-3 |page=i |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Boycott |first=Rosie |url=https://archive.org/details/nicegirllikemest0000boyc/page/88/mode/2up?q=collective |title=A Nice Girl Like Me |date=1985 |publisher=Pan |isbn=978-0-330-28555-1 |location=London |pages=88}}</ref> The collective editorial policy was to "collectively decide on articles that they publish, and work closely with the contributors. Accept articles from men only when there is no other resource available."<ref name="grf"/> Drew Howie was a consultant through 1990-1993. |

||

==Design== |

==Design== |

||

According to Marsha Rowe, one of the original magazine designers, the "look" of ''Spare Rib'' |

According to Marsha Rowe, one of the original magazine designers, the "look" of ''Spare Rib'' was born out of necessity: it had to look like a [[List of women's magazines|women's magazine]], yet with contents that did not reflect conformist stereotyping of women. ''Spare Rib'' covers were often controversial.<ref name=":1"/> The design had to be both stable and flexible to allow for future change while retaining the basic identity. Integral to every decision was cost.<ref name=":1"/> |

||

New, young illustrators and photographers were keen to work for the magazine, enjoying the challenge of finding a [[visual language]] to express the new ideas of the magazine. |

|||

Finding non-sexist advertising in accordance with the values of the magazine was another challenge. |

Finding non-sexist advertising in accordance with the values of the magazine was another challenge. |

||

==Legacy== |

==Legacy== |

||

Scholar Laurel Foster wrote in 2022 for the 50th anniversary of ''Spare Rib''{{'}}s first issue: "The self-expression and persuasive writing of the pioneering magazine have their legacy in feminist media today. [...] Because of its standing in feminist history, Spare Rib has become a touchstone for later feminist magazines."<ref name=laurel2022>{{cite news|url=https://theconversation.com/spare-rib-50-years-since-the-groundbreaking-feminist-magazine-first-hit-the-streets-its-legacy-still-inspires-women-186876|title=Spare Rib: 50 years since the groundbreaking feminist magazine first hit the streets – its legacy still inspires women|date=5 August 2022|first=Laurel|last=Foster|work=[[The Conversation (website)|The Conversation]]|access-date=12 August 2022}}</ref> In their 2017 book ''Re-reading Spare Rib'', Angela Smith and Sheila Quaid wrote that ''Spare Rib'' played a key role in the development of second-wave feminist thought and its spread into the [[collective consciousness]].{{sfn|Smith|Quaid|2017|pp=1,9}} |

|||

| ⚫ | It was reported by ''[[The Guardian]]'' in April 2013 that the magazine was due to be relaunched, with |

||

| ⚫ | It was reported by ''[[The Guardian]]'' in April 2013 that the magazine was due to be relaunched, with journalist [[Charlotte Raven]] at the helm.<ref>{{cite news|first=Ben |last=Dowell|url=https://www.theguardian.com/media/2013/apr/25/sarah-raven-relaunch-spare-rib |title=Spare Rib magazine to be relaunched by Charlotte Raven|newspaper=The Guardian|date= 25 April 2013}}</ref> It was subsequently announced that while a magazine and website were to be launched, they would have a different name.<ref>{{cite news|first=Charlotte|last= Raven|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/10138461/My-wounding-battle-with-Spare-Rib-founders-over-feminism-2.0.html |title=My 'wounding' battle with Spare Rib founders over feminism 2.0|newspaper=[[Daily Telegraph|The Telegraph]]|date=24 June 2013}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/press/spare-rib-founders-threaten-legal-action-over-magazine-relaunch-8658161.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220524/https://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/press/spare-rib-founders-threaten-legal-action-over-magazine-relaunch-8658161.html |archive-date=24 May 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live|title='Spare Rib' founders threaten legal action over magazine relaunch|newspaper=The Independent|first=Liam |last=Obrien|date=13 June 2013|language=en-GB|access-date=8 March 2016}}</ref> |

||

In May 2015, the [[British Library]] put its complete archive of ''Spare Rib'' online.<ref name=": |

In May 2015, the [[British Library]] put its complete [[archive]] of ''Spare Rib'' online.<ref name=":0Davies,">{{Cite news |last=Davies |first=Caroline |date=2015-05-28 |title=Spare Rib goes digital: 21 years of radical feminist magazine put online |url=https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/may/28/british-library-spare-rib-feminist-magazine-online |access-date=2024-10-02 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> The project was led by [[Polly Russell]], the curator behind an [[oral history]] of the [[women's liberation movement]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Women's Liberation Movement |url=https://www.bl.uk/events/secondary-womens-liberation-movement |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190414104428/https://www.bl.uk/events/secondary-womens-liberation-movement |archive-date=14 April 2019 |access-date= |website=The British Library |language=en |quote=Join Polly Russell, Lead Curator for Contemporary Archives and Manuscripts, for a discussion on feminism. Polly was the British Library lead on Sisterhood and After, a project and website to create the UK's first ever oral history archive of the Women's Liberation Movement. Polly was also the lead for a project which digitised and made freely available the feminist magazine Spare Rib.}}</ref> The archive was presented with new views on the subject matter and themes, curated by expert commentators. The British Library website describes the value of ''Spare Rib'' for current readers and researchers:<ref name=":0" /> |

||

{{ |

{{blockquote|''Spare Rib'' was the largest feminist circulating magazine of the Women's Liberation Movement (WLM) in Britain of the 1970s and 80s. It remains one of the movement's most visible achievements. The trajectory of Spare Rib charted the rise and demise of the Women's Liberation Movement and as a consequence is of interest to feminist historians, academics and activists and to those studying social movements and media history.}} |

||

In February 2019 the British Library announced a possible suspension of access to the archive in the event of a no-deal [[Brexit]], due to |

In February 2019, the British Library announced a possible suspension of access to the archive in the event of a no-deal [[Brexit]], due to problems relating to copyright.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://blogs.bl.uk/socialscience/2019/02/spare-rib-archive-possible-suspension-of-access.html|title=Spare Rib Archive - possible Suspension of Access|work=The British Library|first=Polly|last=Russell|date=19 February 2019|access-date=19 February 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/media/2019/feb/25/spare-rib-digital-archive-no-deal-brexit-british-library|work=The Guardian|title=Spare Rib digital archive faces closure in event of no-deal Brexit|first=Lisa|last=O'Carroll|date=25 February 2019}}</ref> It was announced in December 2020 that access would be withdrawn at the end of the transition period.<ref>{{cite web |author=Cooke |first=Ian |date=16 December 2020 |title=Digitised Spare Rib resource |url=https://blogs.bl.uk/socialscience/2020/12/digitised-spare-rib-resource.html |access-date=14 October 2023 |work=Social Science blog |publisher=[[British Library]]}}</ref> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20190414104428/https://www.bl.uk/events/secondary-womens-liberation-movement ''Spare Rib'' collection at the LSE Women's Library] |

|||

* An extensive collection of most if not all publications can be found in the [http://www.londonmet.ac.uk/thewomenslibrary Women's Library] reference/reading room in London. |

|||

*[ |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20080615142631/https://www.bristol.ac.uk/Depts/History/Sixties/Feminism/publications.htm History of ''Spare Rib'' from the Bristol University History Department] |

||

*[http://www.thefword.org.uk/features/2008/01/marsha_rowe Interview with Marsha Rowe] |

*[http://www.thefword.org.uk/features/2008/01/marsha_rowe Interview with Marsha Rowe]. 31 January 2008. Retrieved June 2008. |

||

*{{cite web |last1=O'Sullivan |first1=Sue |title=Feminists and Flourbombs |url=http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/F/flourbombs/essay.html |publisher=Channel 4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080916221109/http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/F/flourbombs/essay.html |archive-date=16 September 2008 |url-status=dead}} |

*{{cite web |last1=O'Sullivan |first1=Sue |title=Feminists and Flourbombs |url=http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/F/flourbombs/essay.html |publisher=Channel 4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080916221109/http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/F/flourbombs/essay.html |archive-date=16 September 2008 |url-status=dead}} |

||

*[http://www.aidanbell.com/pdfs/sparerib.pdf |

*[http://www.aidanbell.com/pdfs/sparerib.pdf ''Spare Rib''] by Hazel K. Bell. The National Housewives Register's ''Newsletter'' no. 19, Autumn 1975, pp. 10–11. Retrieved June 2008. |

||

* {{cite book|last1 = Steiner | first1 = Linda | last2 = Chambers | first2 = Deborah | last3 = Fleming | first3 = Carole | author-link1 = Linda Steiner | contribution = Women's alternative media in broadcasting and the Internet | editor-last1 = Steiner|editor-first1=Linda | editor-last2 = Chambers | editor-first2 = Deborah | editor-last3 = Fleming | editor-first3 = Carole | editor-link1 = Linda Steiner | title = Women and journalism | page = 166 | publisher = Routledge | location = London New York | year = 2004 | isbn = |

* {{cite book| last1=Smith|first1=Angela|last2=Quaid|first2=Sheila|chapter=Introduction|editor-last=Smith|editor-first=Angela|title=Re-reading Spare Rib|year=2017|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|location=|pages=1–21|isbn=978-3-319-49309-1}} |

||

* {{cite book|last1 = Steiner | first1 = Linda | last2 = Chambers | first2 = Deborah | last3 = Fleming | first3 = Carole | author-link1 = Linda Steiner | contribution = Women's alternative media in broadcasting and the Internet | editor-last1 = Steiner|editor-first1=Linda | editor-last2 = Chambers | editor-first2 = Deborah | editor-last3 = Fleming | editor-first3 = Carole | editor-link1 = Linda Steiner | title = Women and journalism | page = 166 | publisher = Routledge | location = London New York | year = 2004 | isbn = 978-0-203-50066-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=olAJxqGZ6VkC&pg=PT166}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

* {{cite book | last = Fell | first = Alison | author-link = Alison Fell | title = Hard Feelings: Fiction and Poetry from Spare Rib | publisher = [[Women's Press Ltd.]] | location = London | year = 1979 | isbn = |

* {{cite book | last = Fell | first = Alison | author-link = Alison Fell | title = Hard Feelings: Fiction and Poetry from Spare Rib | publisher = [[Women's Press Ltd.]] | location = London | year = 1979 | isbn = 978-0-7043-3838-8 }} |

||

* {{cite book | last = Rowe | first = Marsha | author-link = Marsha Rowe | title = Spare Rib Reader | publisher = Penguin Books | location = Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England New York, NY, U.S.A | year = 1982 | isbn = |

* {{cite book | last = Rowe | first = Marsha | author-link = Marsha Rowe | title = Spare Rib Reader | publisher = Penguin Books | location = Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England New York, NY, U.S.A | year = 1982 | isbn = 978-0-14-005250-3 }} |

||

* {{cite book | last = Boycott | first = Rosie | author-link = Rosie Boycott | title = A Nice Girl Like Me | publisher = [[Pocket Books]] | location = London | year = 2009 | orig-year = 1984 | isbn = |

* {{cite book | last = Boycott | first = Rosie | author-link = Rosie Boycott | title = A Nice Girl Like Me | publisher = [[Pocket Books]] | location = London | year = 2009 | orig-year = 1984 | isbn = 978-1-84739-470-5 }} |

||

* {{cite book | last = O'Sullivan | first = Sue | title = Women's Health: A Spare Rib Reader | publisher = Pandora Press | location = London New York | year = 1987 | isbn = |

* {{cite book | last = O'Sullivan | first = Sue | title = Women's Health: A Spare Rib Reader | publisher = Pandora Press | location = London New York | year = 1987 | isbn = 978-0-86358-218-9 }} |

||

* {{cite book | last1 = Cameron | first1 = Deborah | last2 = Scanlon | first2 = Joan | author-link1 = Deborah Cameron (linguist) | title = The Trouble & Strife Reader | publisher = [[Bloomsbury Publishing|Bloomsbury Academic]] | location = London New York | year = 2010 | isbn = 9781849660129 }} Documenting the history of the British magazine ''Trouble and Strife: The Radical Feminist Magazine'', which ran from 1983 to 2002. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://www.bl.uk/spare-rib British Library archive] |

*[http://www.bl.uk/spare-rib British Library archive] |

||

*[http://www.bl.uk/collection-items/facsimile-of-spare-rib-manifesto#sthash.R3Kuul6I.dpuf The ''Spare Rib'' Manifesto at the British Library archive |

*[http://www.bl.uk/collection-items/facsimile-of-spare-rib-manifesto#sthash.R3Kuul6I.dpuf The ''Spare Rib'' Manifesto] at the British Library archive |

||

*[https://journalarchives.jisc.ac.uk/britishlibrary/sparerib Full, free-to-access, online archive hosted by the JISC Journal Archive] |

*[https://journalarchives.jisc.ac.uk/britishlibrary/sparerib Full, free-to-access, online archive hosted by the JISC Journal Archive] |

||

*[http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b039yz4x Marsha Rowe, Rosie Boycott, Angela Phillips, Marion Fudger and Anna Raeburn |

*[http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b039yz4x ''The Reunion'']. Marsha Rowe, Rosie Boycott, [[Angela Phillips]], Marion Fudger and [[Anna Raeburn]] with [[Sue MacGregor]]. BBC Radio 4, September 2013. |

||

*[http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/73951773/Hulton-Archive Photo of Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott] |

*[http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/73951773/Hulton-Archive Photo of Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott] at the magazine's offices, 19 June 1972. |

||

{{UK underground}} |

{{UK underground}} |

||

{{Second-wave feminism}} |

{{Second-wave feminism}} |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

[[Category:Monthly magazines published in the United Kingdom]] |

[[Category:Monthly magazines published in the United Kingdom]] |

||

[[Category:Defunct political magazines published in the United Kingdom]] |

[[Category:Defunct political magazines published in the United Kingdom]] |

||

[[Category:Defunct |

[[Category:Defunct feminist magazines published in the United Kingdom]] |

||

[[Category:Design magazines]] |

[[Category:Design magazines]] |

||

[[Category:Feminism in the United Kingdom]] |

|||

[[Category:Feminist magazines]] |

|||

[[Category:Magazines established in 1972]] |

[[Category:Magazines established in 1972]] |

||

[[Category:Magazines disestablished in 1993]] |

[[Category:Magazines disestablished in 1993]] |

||

[[Category:Magazines published in London]] |

|||

[[Category:Second-wave feminism]] |

[[Category:Second-wave feminism]] |

||

Latest revision as of 06:51, 3 November 2024

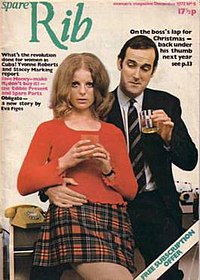

Spare Rib cover, December 1972; featuring John Cleese on the cover | |

| Editor | Collective from late 1973 |

|---|---|

| Categories | Feminist Magazine |

| Founded | 1972 |

| Final issue | 1993 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Website | http://www.bl.uk/spare-rib (archive) |

Spare Rib was a second-wave feminist magazine, founded in 1972 in the United Kingdom, that emerged from the counterculture of the late 1960s as a consequence of meetings involving, among others, Rosie Boycott and Marsha Rowe. Spare Rib is now recognised as having shaped debates about feminism in the UK, and as such it was digitised by the British Library in 2015.[1] The magazine contained new writing and creative contributions that challenged stereotypes and supported collective solutions that related to feminist issues. It was published between 1972 and 1993.[2] The title derives from the Biblical reference to Eve, the first woman, created from Adam's rib.

History

[edit]The first issue of Spare Rib was published in London in June 1972.[3][4] It was distributed by Seymour Press to big chains including W. H. Smith & Son and Menzies — although the former refused to stock issue 13, due to the use of an expletive on the issue's back cover. Selling at first around 20,000 copies a month, it was circulated more widely through women's groups and networks. From 1976, Spare Rib was distributed by Publications Distribution Cooperative to a network of radical and alternative bookshops.

The magazine's purpose, as described in its editorial, was to investigate and present alternatives to the traditional gendered roles of virgin, wife, or mother.[5]

The name Spare Rib started as a joke referring to biblical Eve being fashioned out of Adam's rib, implying that a woman had no independence from the beginning of time.[6]

The Spare Rib manifesto stated:[7]

The concept of Women's Liberation is widely misunderstood, feared and ridiculed. Many women remain isolated and unhappy. We want to publish Spare RIB to try to change this. We believe that women's liberation is of vital importance to women now and, intrinsically, to the future of our society. Spare RIB will reach out to all women, cutting across material, economic and class barriers, to approach them as individuals in their own right.

Early articles were linked closely with left-leaning political theories of the time, especially anti-capitalism and the exploitation of women as consumers through fashion.[citation needed]

As the women's movement evolved during the 1970s, the magazine became a forum for debate among members of the different streams that emerged within the movement, such as socialist feminism, radical feminism, lesbian feminism, liberal feminism, and black feminism.[8] Spare Rib included contributions from well-known international feminist writers, activists, and theorists, as well as stories about ordinary women in their own words. Subjects included the "liberating orgasm", "kitchen sink racism", anorexia, and female genital mutilation. The magazine reflected debates about how best to tackle issues such as sexuality and racism.[9]

Due to falling subscriptions and low advertising revenue, Spare Rib ceased publication in 1993.[3][10]

Editors

[edit]

Spare Rib became a collective by the end of 1973.[11][12] The collective editorial policy was to "collectively decide on articles that they publish, and work closely with the contributors. Accept articles from men only when there is no other resource available."[3] Drew Howie was a consultant through 1990-1993.

Design

[edit]According to Marsha Rowe, one of the original magazine designers, the "look" of Spare Rib was born out of necessity: it had to look like a women's magazine, yet with contents that did not reflect conformist stereotyping of women. Spare Rib covers were often controversial.[6] The design had to be both stable and flexible to allow for future change while retaining the basic identity. Integral to every decision was cost.[6]

Finding non-sexist advertising in accordance with the values of the magazine was another challenge.

Legacy

[edit]Scholar Laurel Foster wrote in 2022 for the 50th anniversary of Spare Rib's first issue: "The self-expression and persuasive writing of the pioneering magazine have their legacy in feminist media today. [...] Because of its standing in feminist history, Spare Rib has become a touchstone for later feminist magazines."[13] In their 2017 book Re-reading Spare Rib, Angela Smith and Sheila Quaid wrote that Spare Rib played a key role in the development of second-wave feminist thought and its spread into the collective consciousness.[14]

It was reported by The Guardian in April 2013 that the magazine was due to be relaunched, with journalist Charlotte Raven at the helm.[15] It was subsequently announced that while a magazine and website were to be launched, they would have a different name.[16][17]

In May 2015, the British Library put its complete archive of Spare Rib online.[9] The project was led by Polly Russell, the curator behind an oral history of the women's liberation movement.[18] The archive was presented with new views on the subject matter and themes, curated by expert commentators. The British Library website describes the value of Spare Rib for current readers and researchers:[1]

Spare Rib was the largest feminist circulating magazine of the Women's Liberation Movement (WLM) in Britain of the 1970s and 80s. It remains one of the movement's most visible achievements. The trajectory of Spare Rib charted the rise and demise of the Women's Liberation Movement and as a consequence is of interest to feminist historians, academics and activists and to those studying social movements and media history.

In February 2019, the British Library announced a possible suspension of access to the archive in the event of a no-deal Brexit, due to problems relating to copyright.[19][20] It was announced in December 2020 that access would be withdrawn at the end of the transition period.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "About the Spare Rib Digitisation Project". The British Library. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019.

- ^ Epps, Philomena (18 April 2016). "A short history of the most radical DIY magazines". Dazed. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ a b c "Spare Rib (Magazine, 1972-1993)". Grassroots Feminism. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Jordan, Justine; Boycott, Rosie; Rowe, Marsha (11 June 2018). "How we made: Spare Rib magazine". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ "Women's History Month: Spare Rib". Women's History Network. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Rowe, Marsha (28 May 2015). "The design of Spare Rib". Creative Review. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Facsimile of Spare Rib manifesto". The British Library. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Sue. "Feminists and Flourbombs". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008.

- ^ a b Davies, Caroline (28 May 2015). "Spare Rib goes digital: 21 years of radical feminist magazine put online". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ Zobl, Elke; Drüeke, Ricarda, eds. (30 April 2014). Feminist Media: Participatory Spaces, Networks and Cultural Citizenship. Critical Studies in Media and Communication. Vol. 9. Transcript Verlag. p. 56. ISBN 978-3-8394-2157-4. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Rowe, Marsha (1982). Spare Rib Reader. Penguin Books. p. i. ISBN 978-0-14-005250-3.

- ^ Boycott, Rosie (1985). A Nice Girl Like Me. London: Pan. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-330-28555-1.

- ^ Foster, Laurel (5 August 2022). "Spare Rib: 50 years since the groundbreaking feminist magazine first hit the streets – its legacy still inspires women". The Conversation. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Smith & Quaid 2017, pp. 1, 9.

- ^ Dowell, Ben (25 April 2013). "Spare Rib magazine to be relaunched by Charlotte Raven". The Guardian.

- ^ Raven, Charlotte (24 June 2013). "My 'wounding' battle with Spare Rib founders over feminism 2.0". The Telegraph.

- ^ Obrien, Liam (13 June 2013). "'Spare Rib' founders threaten legal action over magazine relaunch". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "Women's Liberation Movement". The British Library. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019.

Join Polly Russell, Lead Curator for Contemporary Archives and Manuscripts, for a discussion on feminism. Polly was the British Library lead on Sisterhood and After, a project and website to create the UK's first ever oral history archive of the Women's Liberation Movement. Polly was also the lead for a project which digitised and made freely available the feminist magazine Spare Rib.

- ^ Russell, Polly (19 February 2019). "Spare Rib Archive - possible Suspension of Access". The British Library. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ O'Carroll, Lisa (25 February 2019). "Spare Rib digital archive faces closure in event of no-deal Brexit". The Guardian.

- ^ Cooke, Ian (16 December 2020). "Digitised Spare Rib resource". Social Science blog. British Library. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Spare Rib collection at the LSE Women's Library

- History of Spare Rib from the Bristol University History Department

- Interview with Marsha Rowe. 31 January 2008. Retrieved June 2008.

- O'Sullivan, Sue. "Feminists and Flourbombs". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008.

- Spare Rib by Hazel K. Bell. The National Housewives Register's Newsletter no. 19, Autumn 1975, pp. 10–11. Retrieved June 2008.

- Smith, Angela; Quaid, Sheila (2017). "Introduction". In Smith, Angela (ed.). Re-reading Spare Rib. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-3-319-49309-1.

- Steiner, Linda; Chambers, Deborah; Fleming, Carole (2004). "Women's alternative media in broadcasting and the Internet". In Steiner, Linda; Chambers, Deborah; Fleming, Carole (eds.). Women and journalism. London New York: Routledge. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-203-50066-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Fell, Alison (1979). Hard Feelings: Fiction and Poetry from Spare Rib. London: Women's Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7043-3838-8.

- Rowe, Marsha (1982). Spare Rib Reader. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England New York, NY, U.S.A: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-005250-3.

- Boycott, Rosie (2009) [1984]. A Nice Girl Like Me. London: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-1-84739-470-5.

- O'Sullivan, Sue (1987). Women's Health: A Spare Rib Reader. London New York: Pandora Press. ISBN 978-0-86358-218-9.

External links

[edit]- British Library archive

- The Spare Rib Manifesto at the British Library archive

- Full, free-to-access, online archive hosted by the JISC Journal Archive

- The Reunion. Marsha Rowe, Rosie Boycott, Angela Phillips, Marion Fudger and Anna Raeburn with Sue MacGregor. BBC Radio 4, September 2013.

- Photo of Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott at the magazine's offices, 19 June 1972.

- 1972 establishments in the United Kingdom

- 1993 disestablishments in the United Kingdom

- Anti-capitalism

- British design

- Monthly magazines published in the United Kingdom

- Defunct political magazines published in the United Kingdom

- Defunct feminist magazines published in the United Kingdom

- Design magazines

- Magazines established in 1972

- Magazines disestablished in 1993

- Magazines published in London

- Second-wave feminism