Young Beichan: Difference between revisions

m sp, ce |

HouseBlaster (talk | contribs) Moving from Category:Songwriter unknown to Category:Songs with unknown songwriters implement Wikipedia:Categories for discussion/Log/2024 October 19#Category:Songwriter unknown using Cat-a-lot |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| name = Young Beichan |

| name = Young Beichan |

||

| catalogue = [[Child Ballad]] 53 |

| catalogue = [[Child Ballad]] 53 |

||

| type = [[Ballad]] |

|year=Earlier than 1783| type = [[Ballad]] |

||

| composer = Unknown |

| composer = Unknown |

||

|image=}} |

|||

| text = by unknown |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Image:Young Beckie by Arthur Rackham.jpg|right|thumb|Illustration by [[Arthur Rackham]]: Young Beckie in prison.]] |

|||

"'''Young Beichan'''" |

"'''Young Beichan'''", also known as "'''Lord Bateman", "Lord Bakeman", "Lord Baker", "Young Bicham" and "Young Bekie",''' is a traditional folk ballad categorised as [[Child ballads|Child ballad]] [[List of the Child Ballads|53]] and [[Roud Folk Song Index|Roud]] [[List of folk songs by Roud number|40]].<ref>[[Francis James Child]], ''English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch053.htm "Young Beichan"]</ref> The earliest versions date from the late 18th century, but it is probably older, with clear parallels in ballads and folktales across Europe. The song was popular as a broadside ballad in the nineteenth century, and survived well into the twentieth century in the oral tradition in rural areas of most English speaking parts of the world, particularly in [[England]], [[Scotland]] and [[Appalachia]]. |

||

==Synopsis== |

==Synopsis== |

||

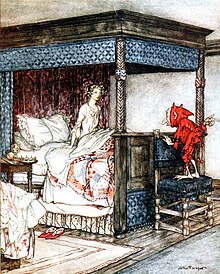

[[File:Illustration_to_the_ballad_Young_Beckie_from_"Some_British_Ballads".jpg|left|thumb|Illustration by Arthur Rackham: Burd Isbel woken by Belly Blin, with the warning that Young Beckie is about to marry.]] |

[[File:Illustration_to_the_ballad_Young_Beckie_from_"Some_British_Ballads".jpg|left|thumb|Illustration by [[Arthur Rackham]]: Burd Isbel woken by Belly Blin, with the warning that Young Beckie is about to marry.]] |

||

Beichan is born in London |

Beichan, who is often born in [[London]], travels to far lands. He is taken prisoner, with different captors appearing in different variations, usually being a [[Moors|Moor]] or a [[Turkey|Turk]], though sometimes the [[List of French monarchs|king of France]], before falling in love with his captor’s daughter. Lamenting his fate, Beichan promises to be a son to any married woman who will rescue him, or a husband to an unmarried one. She rescues him, and he leaves, promising to marry her. |

||

He does not return. She sets out after him—in some variants, because warned by a household spirit, [[Belly Blin]], that he is about to marry—and arrives as he is marrying [[false hero|another]]. In some variants, he is constrained to marry; often he is fickle. His porter tells him of a woman at his gate, and he instantly realizes it is the woman who rescued him. He sends his new bride home and marries her. |

He does not return. She sets out after him—in some variants, because warned by a household spirit, [[Belly Blin]], that he is about to marry—and arrives as he is marrying [[false hero|another]]. In some variants, he is constrained to marry; often he is fickle. His porter tells him of a woman at his gate, and he instantly realizes it is the woman who rescued him. He sends his new bride home and marries her. |

||

== |

==History== |

||

[[Image:Faroe stamp 070 elinborg waiting for paetur.jpg|thumb|right|Elinborg waiting for Paetur, in a Faroese variant.]] |

[[Image:Faroe stamp 070 elinborg waiting for paetur.jpg|thumb|right|Elinborg waiting for Paetur, in a Faroese variant.|244x244px]] |

||

This ballad is also known in Norse, Spanish, and Italian variants.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', v. 1, p. 459, Dover Publications, New York, 1965</ref> |

|||

=== Parallels === |

|||

In a Scandinavian variant, "Harra Pætur og Elinborg" ([[Corpus Carminum Færoensium|CCF]] 158, [[The Types of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballad|TSB]] D 72), the hero set out on a pilgrimage, after asking the heroine, his betrothed, how long she would wait for him; she says, eight years. After the eight years, she sets out and the rest of the ballad is the same, except that Paetur has a reason for his fickleness: he was magically made to forget.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', v. 1, pp. 459–61, Dover Publications, New York 1965</ref> |

This ballad is also known in Norse, Spanish, and Italian variants.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', v. 1, p. 459, Dover Publications, New York, 1965</ref> In a Scandinavian variant, "Harra Pætur og Elinborg" ([[Corpus Carminum Færoensium|CCF]] 158, [[The Types of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballad|TSB]] D 72), the hero set out on a pilgrimage, after asking the heroine, his betrothed, how long she would wait for him; she says, eight years. After the eight years, she sets out and the rest of the ballad is the same, except that Paetur has a reason for his fickleness: he was magically made to forget.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', v. 1, pp. 459–61, Dover Publications, New York 1965</ref> |

||

The motif of a hero magically made to forget his love and remembering her on her appearance is common; it may even have been dropped from "Young Beichan", as the hero always returns to the heroine with a promptness of an enchantment breaking.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', v. 1, p. 461, Dover Publications, New York 1965</ref> Other folktales with this motif include "[[Jean, the Soldier, and Eulalie, the Devil's Daughter]]" |

The motif of a hero magically made to forget his love and remembering her on her appearance is common; it may even have been dropped from "Young Beichan", as the hero always returns to the heroine with a promptness of an enchantment breaking.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads'', v. 1, p. 461, Dover Publications, New York 1965</ref> This motif is known as ''[[The Forgotten Fiancée]]'' and appears as a final episode of tales classified in the [[Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index]] as type ATU 313, "The Magic Flight: Girl helps the hero flee".<ref>Goldberg, Christine. "The Forgotten Bride (AaTh 313 C)". Fabula 33, 1-2 (1992): 51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1992.33.1-2.39</ref> Other folktales with this motif include "[[Jean, the Soldier, and Eulalie, the Devil's Daughter]]" (France); "[[The Two Kings' Children]]", "[[The True Bride]]" and "[[Sweetheart Roland]]" (Germany); "[[The Master Maid]]" (Norway), "[[Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa]]" (Greece) and "[[Snow-White-Fire-Red]]" (Sicily). |

||

Another British-derived folk song, "The Turkish Lady" ([[List of folk songs by Roud number|Roud 8124]]), appears to be somewhat related; it didn't diverge recently, being noted as early as 1768.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=No. 53: Young Beichan (or Young Bekie) also (Lord Bateman)|url=http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/53-young-beichan-or-young-bekie.aspx|website=Bluegrass Messengers}}</ref> |

|||

=== Gilbert Beckett === |

|||

According to the folklorist [[Frank Kidson]], it has been "asserted, with every appearance of truth" that the protagonist is in fact Gilbert Becket, the father of [[Thomas Becket|Saint Thomas Becket]], who was supposedly captured in the [[Crusades]] as in the ballad, released, and followed to London by a lady he met there. Kidson claimed that "Bateman", "Baker" and "Beichie" were all corruptions of "[[Beckett]]".<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kidson|first=Frank|title=Traditional Tunes|publisher=Oxford: Chas. Taphouse & Son.|year=1891|pages=33}}</ref> [[Francis James Child]] said "That our ballad has been affected by the legend of Gilbert Beket is altogether likely”,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Young Beichan / Lord Bateman (Roud 40; Child 53L; G/D 5:1023; Henry H470)|url=https://mainlynorfolk.info/joseph.taylor/songs/lordbateman.html|access-date=2021-10-25|website=mainlynorfolk.info}}</ref> suggesting that the two similar stories may have influenced each other. |

|||

=== Distribution === |

|||

The ballad was very popular in print in the 1800s, with most [[Broadside ballad|broadsides]] descending from one printed in England around 1815, beginning "Lord Bateman was a noble lord..." (see texts below).<ref name=":0" /> Most of the versions that ended up in America were derived from popular broadside versions, however some versions, such as one known to the [[Ray Hicks|Hicks]]-Harmon family of [[Watauga County, North Carolina|Watuaga County]], [[North Carolina]], seemed to have been passed on from an older British oral tradition.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

==Traditional Recordings== |

==Traditional Recordings== |

||

[[File:Joseph Taylor in booklet from 'Percy Grainger's Collection of English Folk-Songs sung by Genuine Peasant Performers'.png|thumb|195x195px|[[Joseph Taylor (folk singer)|Joseph Taylor]]]] |

|||

In 1908 [[Percy Grainger]] made several [[Phonograph cylinder|wax cylinder]] recordings of traditional singers singing the ballad. Several of these were recorded in Lincolnshire (including one version by [[Joseph Taylor (folk singer)|Joseph Taylor]]) and one in Gloucestershire; all of the recordings are available courtesy of the [[British Library Sound Archive]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010303XX-0102V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (second performance, part 1) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010289XX-0202V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (second performance, parts 1 and 2) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010283XX-0201V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (part 1) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010270XX-0101V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref> Dozens of other traditional versions were recorded across England later in the twentieth century.<ref>{{Cite web |

In 1908 [[Percy Grainger]] made several [[Phonograph cylinder|wax cylinder]] recordings of traditional singers singing the ballad. Several of these were recorded in [[Lincolnshire]] (including one version by [[Joseph Taylor (folk singer)|Joseph Taylor]]) and one in [[Gloucestershire]]; all of the recordings are available courtesy of the [[British Library Sound Archive]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010303XX-0102V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (second performance, part 1) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010289XX-0202V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (second performance, parts 1 and 2) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010283XX-0201V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (part 1) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music {{!}} British Library - Sounds|url=https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Percy-Grainger-Collection/025M-1LL0010270XX-0101V0|access-date=2020-11-23|website=sounds.bl.uk}}</ref> Dozens of other traditional versions were recorded across England later in the twentieth century.<ref>{{Cite web|title=VWML Search: rn40 sound england|url=https://www.vwml.org/search?q=rn40%20sound%20england&is=1|website=Vaughan Williams Memorial Library}}</ref> Several of these, some of which are fragments, can be heard on the [[Vaughan Williams Memorial Library]], including a version the [[Dorset]] traveller Caroline Hughes sang to [[Ewan MacColl|Ewan McColl]] and [[Peggy Seeger]] in the 1960s,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S370346)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S370346|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> a 1967 performance by a Frank Smith of [[Edenbridge, Kent|Edenbridge]], [[Kent]],<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN29647)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/VWMLSongIndex/SN29647|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> and a 1960 version sung by Tom Willet of [[Ashford, Surrey|Ashford]], [[Surrey]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN29414)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/VWMLSongIndex/SN29414|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> |

||

The Scottish traditional singer [[Jeannie Robertson]] sang a version to [[Peter Kennedy (folklorist)|Peter Kennedy]] in 1958,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Susan Pyatt (Roud Folksong Index S222542)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S222542|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> whilst Bella Higgins sang another to [[Hamish Henderson]] in 1955.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S430496)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S430496|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> Several other Scottish recordings were made, including some recorded by [[James Madison Carpenter]] which are also available on the [[Vaughan Williams Memorial Library]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN15991)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/VWMLSongIndex/SN15991|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Brichen (VWML Song Index SN16011)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/VWMLSongIndex/SN16011|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> |

The Scottish traditional singer [[Jeannie Robertson]] sang a version to [[Peter Kennedy (folklorist)|Peter Kennedy]] in 1958,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Susan Pyatt (Roud Folksong Index S222542)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S222542|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> whilst Bella Higgins sang another to [[Hamish Henderson]] in 1955.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S430496)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S430496|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> Several other Scottish recordings were made, including some recorded by [[James Madison Carpenter]] which are also available on the [[Vaughan Williams Memorial Library]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN15991)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/VWMLSongIndex/SN15991|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Brichen (VWML Song Index SN16011)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/VWMLSongIndex/SN16011|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> |

||

The influential [[Appalachian Mountains|Appalachian]] folk singer [[Jean Ritchie]] had her family version of the ballad recorded several times, including on her album ''Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition'' (1961).<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S213524)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S213524|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=The Turkish Lady (Roud Folksong Index S318152)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S318152|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> Her fellow Appalachian [[Nimrod Workman]] sang his own traditional version |

The influential [[Appalachian Mountains|Appalachian]] folk singer [[Jean Ritchie]] had her family version of the ballad recorded several times, including on her album ''Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition'' (1961).<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S213524)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S213524|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=The Turkish Lady (Roud Folksong Index S318152)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S318152|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> Her fellow Appalachian [[Nimrod Workman]] sang his own traditional version on different occasions,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S331493)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S331493|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> including on a YouTube video uploaded by the official Alan Lomax archive channel.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Nimrod Workman: Lord Baseman (1983)|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r5FZt0kV9zk&t=312s |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211221/r5FZt0kV9zk |archive-date=2021-12-21 |url-status=live|website=YouTube| date=4 October 2011 }}{{cbignore}}</ref> Other noted Appalachian musicians, such as [[Aunt Molly Jackson]] (1935),<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S262154)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S262154|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> Eliza Pace (1937),<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S262156)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S262156|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> [[Virgil Sturgill]] (1958)<ref>{{Cite web|title=Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S389611)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S389611|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> and Buna Hicks (1961)<ref>{{Cite web|title=Young Beham (Roud Folksong Index S226730)|url=https://www.vwml.org/record/RoudFS/S226730|access-date=2020-11-23|website=The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library|language=en-gb}}</ref> had traditional versions recorded. |

||

The folklorist [[Helen Hartness Flanders]] recorded many versions in her native [[New England]],<ref>{{Cite web |

The folklorist [[Helen Hartness Flanders]] recorded many versions in her native [[New England]],<ref>{{Cite web|title=Search: rn40 sound usa flanders|url=https://www.vwml.org/search?q=rn40%20sound%20usa%20flanders&is=1|website=Vaughan Williams Memorial Library}}</ref> and Canadian collectors including Helen Creighton and Kenneth Peacock recorded several versions in [[Newfoundland (island)|Newfoundland]] and [[Nova Scotia]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Search: rn40 sound canada|url=https://www.vwml.org/search?q=rn40%20sound%20canada&is=1|website=Vaughan Williams Memorial Library}}</ref> |

||

== Text == |

|||

[[Image:Young Beckie by Arthur Rackham.jpg|right|thumb|Illustration by [[Arthur Rackham]]: Young Beckie in prison.]]The first four verses of the oldest version of the ballad, 'Young Bicham', [[Francis James Child|Child]]'s ''Version A'', from 1783: (The second verse describes Bicham's captor boring a hole through his shoulder to harness him for use as a [[Working animal|draft animal]])<ref name=":0" /><blockquote>In [[London]] city was Bicham born, |

|||

He longd strange countries for to see, |

|||

But he was taen by a savage [[Moors|Moor]], |

|||

Who handld him right cruely. |

|||

For thro his shoulder he put a bore, |

|||

An thro the bore has pitten a tree, |

|||

An he's gard him draw the carts o wine, |

|||

Where horse and oxen had wont to be. |

|||

He's casten [him] in a dungeon deep, |

|||

Where he coud neither hear nor see; |

|||

He's shut him up in a prison strong, |

|||

An he's handld him right cruely. |

|||

O this Moor he had but ae daughter, |

|||

I wot her name was Shusy Pye; |

|||

She's doen her to the prison-house, |

|||

And she's calld Young Bicham one word by.<ref name=":0" /></blockquote> |

|||

In 1839, the illustrator [[George Cruikshank]] published an illustrated book called "The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman", which tells the story of the ballad.<ref>{{Cite web|title=George Cruikshank (1792-1878) - The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman with XI plates.|url=https://www.rct.uk/collection/817008/the-loving-ballad-of-lord-bateman-with-xi-plates|access-date=2021-10-25|website=www.rct.uk|language=en}}</ref> This version was close to the popular broadside ballads of the nineteenth century and most of the versions which survived in the oral tradition until the twentieth century. The first four verses of this version (below) can be compared to the older "Young Bicham" version (above).<blockquote>Lord Bateman was a noble lord, |

|||

A noble lord of high degree; |

|||

He shipped himself all aboard of a ship, |

|||

Some foreign country for to see. |

|||

He sailed east, he sailed west, |

|||

Until he came to famed [[Turkey]], |

|||

Where he was taken and put to prison, |

|||

Until his life was quite weary. |

|||

All in this prison there grew a tree, |

|||

O there it grew so stout and strong! |

|||

Where he was chained all by the middle, |

|||

Until his life was almost gone. |

|||

This Turk he had one only daughter, |

|||

The fairest my two eyes eer see; |

|||

She steel the keys of her father's prison, |

|||

And swore Lord Bateman she would let go free.<ref name=":0" /></blockquote> |

|||

== Popular Recordings == |

== Popular Recordings == |

||

| Line 44: | Line 116: | ||

* [[Steve Ashley]] on ''Stroll On'' (1974) (as "Lord Bateman") |

* [[Steve Ashley]] on ''Stroll On'' (1974) (as "Lord Bateman") |

||

* [[Planxty]] on ''Words and Music'' (1983) (as "Lord Baker") |

* [[Planxty]] on ''Words and Music'' (1983) (as "Lord Baker") |

||

* [[Broadside Electric]] on ''[[More Bad News ...]]'' (1996) (as "Lord Bateman") |

|||

* [[June Tabor]] on ''On Air'' (1998) |

* [[June Tabor]] on ''On Air'' (1998) |

||

* [[Susan McKeown]] on [[Lowlands (Susan McKeown album)|''Lowlands'']] (2000) (as "Lord Baker") |

* [[Susan McKeown]] on [[Lowlands (Susan McKeown album)|''Lowlands'']] (2000) (as "Lord Baker") |

||

| Line 56: | Line 127: | ||

* [[Hind Horn]] |

* [[Hind Horn]] |

||

* [[List of the Child Ballads]] |

* [[List of the Child Ballads]] |

||

==Footnotes== |

|||

{{notelist|}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/faculty/stampe/Oral-Lit/English/Child-Ballads/child.html#53 "Young Beichan"] |

* [http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/faculty/stampe/Oral-Lit/English/Child-Ballads/child.html#53 "Young Beichan"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060218071235/http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/faculty/stampe/Oral-Lit/English/Child-Ballads/child.html#53 |date=2006-02-18 }} |

||

* [http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/teach/ballads/beigham.html "Lord Beigham", 19th-century broadside] |

* [http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/teach/ballads/beigham.html "Lord Beigham", 19th-century broadside] |

||

* [http://www.annaandelizabeth.com/crankies.html Video of a gradually scrolling panorama of illustrations of this ballad] that arrive inside a stationary frame when the lyrics that they illustrate are sung. |

* [http://www.annaandelizabeth.com/crankies.html Video of a gradually scrolling panorama of illustrations of this ballad] that arrive inside a stationary frame when the lyrics that they illustrate are sung. |

||

{{Francis James Child}} |

{{Francis James Child}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:19th-century songs]] |

[[Category:19th-century songs]] |

||

[[Category:Child Ballads]] |

[[Category:Child Ballads]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Jean Ritchie songs]] |

||

[[Category:Songs with unknown songwriters]] |

|||

[[Category:Year of song unknown]] |

[[Category:Year of song unknown]] |

||

[[Category:ATU 300-399]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 00:16, 27 October 2024

| Young Beichan | |

|---|---|

| Ballad by Unknown | |

| Catalogue | Child Ballad 53 |

| Year | Earlier than 1783 |

"Young Beichan", also known as "Lord Bateman", "Lord Bakeman", "Lord Baker", "Young Bicham" and "Young Bekie", is a traditional folk ballad categorised as Child ballad 53 and Roud 40.[1] The earliest versions date from the late 18th century, but it is probably older, with clear parallels in ballads and folktales across Europe. The song was popular as a broadside ballad in the nineteenth century, and survived well into the twentieth century in the oral tradition in rural areas of most English speaking parts of the world, particularly in England, Scotland and Appalachia.

Synopsis

[edit]

Beichan, who is often born in London, travels to far lands. He is taken prisoner, with different captors appearing in different variations, usually being a Moor or a Turk, though sometimes the king of France, before falling in love with his captor’s daughter. Lamenting his fate, Beichan promises to be a son to any married woman who will rescue him, or a husband to an unmarried one. She rescues him, and he leaves, promising to marry her.

He does not return. She sets out after him—in some variants, because warned by a household spirit, Belly Blin, that he is about to marry—and arrives as he is marrying another. In some variants, he is constrained to marry; often he is fickle. His porter tells him of a woman at his gate, and he instantly realizes it is the woman who rescued him. He sends his new bride home and marries her.

History

[edit]

Parallels

[edit]This ballad is also known in Norse, Spanish, and Italian variants.[2] In a Scandinavian variant, "Harra Pætur og Elinborg" (CCF 158, TSB D 72), the hero set out on a pilgrimage, after asking the heroine, his betrothed, how long she would wait for him; she says, eight years. After the eight years, she sets out and the rest of the ballad is the same, except that Paetur has a reason for his fickleness: he was magically made to forget.[3]

The motif of a hero magically made to forget his love and remembering her on her appearance is common; it may even have been dropped from "Young Beichan", as the hero always returns to the heroine with a promptness of an enchantment breaking.[4] This motif is known as The Forgotten Fiancée and appears as a final episode of tales classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as type ATU 313, "The Magic Flight: Girl helps the hero flee".[5] Other folktales with this motif include "Jean, the Soldier, and Eulalie, the Devil's Daughter" (France); "The Two Kings' Children", "The True Bride" and "Sweetheart Roland" (Germany); "The Master Maid" (Norway), "Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa" (Greece) and "Snow-White-Fire-Red" (Sicily).

Another British-derived folk song, "The Turkish Lady" (Roud 8124), appears to be somewhat related; it didn't diverge recently, being noted as early as 1768.[6]

Gilbert Beckett

[edit]According to the folklorist Frank Kidson, it has been "asserted, with every appearance of truth" that the protagonist is in fact Gilbert Becket, the father of Saint Thomas Becket, who was supposedly captured in the Crusades as in the ballad, released, and followed to London by a lady he met there. Kidson claimed that "Bateman", "Baker" and "Beichie" were all corruptions of "Beckett".[7] Francis James Child said "That our ballad has been affected by the legend of Gilbert Beket is altogether likely”,[8] suggesting that the two similar stories may have influenced each other.

Distribution

[edit]The ballad was very popular in print in the 1800s, with most broadsides descending from one printed in England around 1815, beginning "Lord Bateman was a noble lord..." (see texts below).[6] Most of the versions that ended up in America were derived from popular broadside versions, however some versions, such as one known to the Hicks-Harmon family of Watuaga County, North Carolina, seemed to have been passed on from an older British oral tradition.[6]

Traditional Recordings

[edit]

In 1908 Percy Grainger made several wax cylinder recordings of traditional singers singing the ballad. Several of these were recorded in Lincolnshire (including one version by Joseph Taylor) and one in Gloucestershire; all of the recordings are available courtesy of the British Library Sound Archive.[9][10][11][12] Dozens of other traditional versions were recorded across England later in the twentieth century.[13] Several of these, some of which are fragments, can be heard on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, including a version the Dorset traveller Caroline Hughes sang to Ewan McColl and Peggy Seeger in the 1960s,[14] a 1967 performance by a Frank Smith of Edenbridge, Kent,[15] and a 1960 version sung by Tom Willet of Ashford, Surrey.[16]

The Scottish traditional singer Jeannie Robertson sang a version to Peter Kennedy in 1958,[17] whilst Bella Higgins sang another to Hamish Henderson in 1955.[18] Several other Scottish recordings were made, including some recorded by James Madison Carpenter which are also available on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.[19][20]

The influential Appalachian folk singer Jean Ritchie had her family version of the ballad recorded several times, including on her album Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition (1961).[21][22] Her fellow Appalachian Nimrod Workman sang his own traditional version on different occasions,[23] including on a YouTube video uploaded by the official Alan Lomax archive channel.[24] Other noted Appalachian musicians, such as Aunt Molly Jackson (1935),[25] Eliza Pace (1937),[26] Virgil Sturgill (1958)[27] and Buna Hicks (1961)[28] had traditional versions recorded.

The folklorist Helen Hartness Flanders recorded many versions in her native New England,[29] and Canadian collectors including Helen Creighton and Kenneth Peacock recorded several versions in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia.[30]

Text

[edit]

The first four verses of the oldest version of the ballad, 'Young Bicham', Child's Version A, from 1783: (The second verse describes Bicham's captor boring a hole through his shoulder to harness him for use as a draft animal)[6]

In London city was Bicham born,

He longd strange countries for to see,

But he was taen by a savage Moor,

Who handld him right cruely.

For thro his shoulder he put a bore,

An thro the bore has pitten a tree,

An he's gard him draw the carts o wine,

Where horse and oxen had wont to be.

He's casten [him] in a dungeon deep,

Where he coud neither hear nor see;

He's shut him up in a prison strong,

An he's handld him right cruely.

O this Moor he had but ae daughter,

I wot her name was Shusy Pye;

She's doen her to the prison-house,

And she's calld Young Bicham one word by.[6]

In 1839, the illustrator George Cruikshank published an illustrated book called "The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman", which tells the story of the ballad.[31] This version was close to the popular broadside ballads of the nineteenth century and most of the versions which survived in the oral tradition until the twentieth century. The first four verses of this version (below) can be compared to the older "Young Bicham" version (above).

Lord Bateman was a noble lord,

A noble lord of high degree;

He shipped himself all aboard of a ship,

Some foreign country for to see.

He sailed east, he sailed west,

Until he came to famed Turkey,

Where he was taken and put to prison,

Until his life was quite weary.

All in this prison there grew a tree,

O there it grew so stout and strong!

Where he was chained all by the middle,

Until his life was almost gone.

This Turk he had one only daughter,

The fairest my two eyes eer see;

She steel the keys of her father's prison,

And swore Lord Bateman she would let go free.[6]

Popular Recordings

[edit]- Jean Ritchie on British Traditional Ballads in the Southern Mountains—Child Ballads, Vol 1 (1961)

- Ewan MacColl on The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (Child Ballads)—Vol. 2 (1964) (as "Young Beichan")

- Peter Bellamy on The Fox Jumped Over The Parson's Gate (1969)

- New Lost City Ramblers on Remembrance of Things to Come (1966)

- Nic Jones on Nic Jones (1971) (as "Lord Bateman")

- The New Golden Ring on Five Days Singing, Volume 1 (1971) (as "Lord Bateman")

- Steve Ashley on Stroll On (1974) (as "Lord Bateman")

- Planxty on Words and Music (1983) (as "Lord Baker")

- June Tabor on On Air (1998)

- Susan McKeown on Lowlands (2000) (as "Lord Baker")

- Sinéad O'Connor on Sean-Nós Nua (2002) (as "Lord Baker")

- Jim Moray on Sweet England (2003) (as "Lord Bateman")

- Chris Wood on The Lark Descending (2005) (as "Lord Bateman")

- John Kirkpatrick on Make No Bones (2007)

- The Askew Sisters on Through Lonesome Woods (as "Lord Bateman") (2010)

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Francis James Child, English and Scottish Popular Ballads, "Young Beichan"

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v. 1, p. 459, Dover Publications, New York, 1965

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v. 1, pp. 459–61, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v. 1, p. 461, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. "The Forgotten Bride (AaTh 313 C)". Fabula 33, 1-2 (1992): 51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1992.33.1-2.39

- ^ a b c d e f "No. 53: Young Beichan (or Young Bekie) also (Lord Bateman)". Bluegrass Messengers.

- ^ Kidson, Frank (1891). Traditional Tunes. Oxford: Chas. Taphouse & Son. p. 33.

- ^ "Young Beichan / Lord Bateman (Roud 40; Child 53L; G/D 5:1023; Henry H470)". mainlynorfolk.info. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ "Lord Bateman - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music | British Library - Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (second performance, part 1) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music | British Library - Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (second performance, parts 1 and 2) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music | British Library - Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (part 1) - Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music | British Library - Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "VWML Search: rn40 sound england". Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S370346)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN29647)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN29414)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Susan Pyatt (Roud Folksong Index S222542)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S430496)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (VWML Song Index SN15991)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Brichen (VWML Song Index SN16011)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S213524)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "The Turkish Lady (Roud Folksong Index S318152)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S331493)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Nimrod Workman: Lord Baseman (1983)". YouTube. 4 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S262154)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S262156)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Lord Bateman (Roud Folksong Index S389611)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Young Beham (Roud Folksong Index S226730)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Search: rn40 sound usa flanders". Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

- ^ "Search: rn40 sound canada". Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

- ^ "George Cruikshank (1792-1878) - The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman with XI plates". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

External links

[edit]- "Young Beichan" Archived 2006-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lord Beigham", 19th-century broadside

- Video of a gradually scrolling panorama of illustrations of this ballad that arrive inside a stationary frame when the lyrics that they illustrate are sung.