Irish Crown Jewels: Difference between revisions

Ceremonial --> Ceremony |

m Moving Category:Monarchy in Ireland to Category:Monarchy of Ireland per Wikipedia:Categories for discussion/Speedy |

||

| (315 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|State Jewels of Ireland}} |

|||

| ⚫ | The ''' |

||

{{Use British English|date=October 2013}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2023}} |

|||

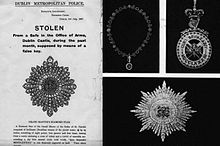

[[Image:Irishcrownjewels.jpg|thumb|250px|Image of the Irish Crown Jewels, as published by the [[Royal Irish Constabulary]] and the [[Dublin Metropolitan Police]] twice a week after the theft of the items was discovered in July 1907.]] |

|||

King [[George III of the United Kingdom|George III]] instituted the Order of St. Patrick in [[1783]]. The Irish Crown Jewels were the insignia of the Order, and consisted of two items: a star, and a badge, each composed of [[ruby|rubies]], [[emerald]]s and [[Brazil]]ian [[diamond]]s. |

|||

| ⚫ | The '''Jewels of the Order of St Patrick''', commonly called the '''Irish Crown Jewels''', were the heavily jewelled badge and star created in 1831 for the Grand Master of the [[Order of St Patrick]], an [[order of knighthood]] established in 1783 by [[George III]] to be an Irish equivalent of the English [[Order of the Garter]] and the Scottish [[Order of the Thistle]]. The office of Grand Master was held by the [[Lord Lieutenant of Ireland]]. |

||

| ⚫ | In [[ |

||

The jewels were stolen from [[Dublin Castle]] in 1907, along with the [[Collar (order)|collars]] of five knights of the order. The theft has never been solved, and the items have never been recovered.<ref name="AO">{{cite web |last1=Nosowitz |first1=Dan |title=The Greatest Unsolved Heist in Irish History |url=https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/irish-crown-jewels-theft |website=Atlas Obscura – Stories |publisher=Atlas Obscura |access-date=5 November 2021 |date=4 November 2021}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Irishcrownjewels.jpg|right|Irish Crown Jewels]] |

|||

==History== |

|||

The jewels were discovered missing on [[6 July]] [[1907]], four days before the State Visit of King [[Edward VII of the United Kingdom|Edward VII]] and Queen [[Alexandra of Denmark|Alexandra]]. The theft is reported to have angered the King (who allegedly exclaimed "I want my jewels") but the visit went ahead. |

|||

[[File:Lord Dudley, Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick.jpg|thumb|right|The [[William Ward, 2nd Earl of Dudley|Earl of Dudley]] as Viceroy of Ireland and Grand Master of the Order of St Patrick.]] |

|||

[[File:The 6th Marquess of Londonderry as viceroy of Ireland.jpg|thumb|The [[Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 6th Marquess of Londonderry|Marquess of Londonderry]] as Viceroy and Grand Master.]] |

|||

The original regalia of the Grand Master were only slightly more opulent than the insignia of an ordinary member of the order; the king's 1783 ordinance said they were to be "of the same materials and fashion as those of Our Knights, save only those alterations which befit Our dignity".<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=9rFXAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA46 ''Statutes and Ordinances'' 1852, pp.46–47]</ref> The regalia were replaced in 1831 by new ones presented by [[William IV]] as part of a revision of the order's structure. They were delivered from London to Dublin on 15 March by the [[William Hay, 18th Earl of Erroll|Earl of Erroll]] in a mahogany box together with a document titled "A Description of the Jewels of the Order of St. Patrick, made by command of His Majesty King William the Fourth, for the use of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and which are Crown Jewels."<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=9rFXAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA104 ''Statutes and Ordinances'' 1852, pp.104–105]</ref> They contained 394 precious stones taken from the [[English Crown Jewels]] of [[Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz|Queen Charlotte]] and the [[Order of the Bath]] star of her husband George III.<ref name="Riordan2001">{{cite journal|last=O'Riordan|first=Tomás|date=Winter 2001|title=The Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels, 1907|journal=History Ireland|volume=9|issue=4|url=http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/the-theft-of-the-irish-crown-jewels-1907/}}</ref> The jewels were assembled by [[Rundell & Bridge]]. On the badge, of [[St Patrick's blue]] enamel, the green [[shamrock]] was of [[emerald]]s and the red [[Saint Patrick's Saltire|saltire]] of [[ruby|rubies]]; the motto of the order was in [[Diamond color|pink diamond]]s and the encrustation was of Brazilian diamonds of the [[first water]].<ref name="Riordan2001"/><ref name="nationalarchives">{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/ |title=The Theft of the Irish 'Crown Jewels' |work=Online exhibitions |date=2007 |access-date=15 June 2013 |publisher=[[National Archives of Ireland]] |location=Dublin |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130511165435/http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/ |archive-date=11 May 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Notices issued after the theft described the jewels thus: |

|||

{{Blockquote |

|||

| A Diamond Star of the Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick composed of [[Brilliant (diamond cut)|brilliants]] (Brazilian stones) of the [[First water|purest water]], {{fraction|4|5|8}} by {{fraction|4|1|4}} inches, consisting of eight points, four greater and four lesser, issuing from a centre enclosing a cross of rubies and a [[trefoil]] of emeralds surrounding a sky blue enamel circle with words, "[[Quis Separabit]] [[1783|MDCCLXXXIII]]." in rose diamonds engraved on back. Value about £14,000. ({{Inflation|UK|14000|1907|r=-4|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}).{{Inflation-fn|UK|df=y}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/photo-gallery/dmp/ |title=DMP – poster 1 |year=2007 |orig-date=Original date 8 July 1907 |publisher=Dublin Metropolitan Police |access-date=15 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140206073814/http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%e2%80%9ccrown-jewels%e2%80%9d-2007/photo-gallery/dmp/ |archive-date=6 February 2014 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Blockquote |

|||

|A Diamond Badge of the Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick set in silver containing a trefoil in emeralds on a ruby cross surrounded by a sky blue enamelled circle with "Quis Separabit MDCCLXXXIII." in rose diamonds surrounded by a wreath of trefoils in emeralds, the whole enclosed by a circle of large single Brazilian stones of the finest water, surmounted by a crowned harp in diamonds and loop, also in Brazilian stones. Total size of oval 3 by {{fraction|2|3|8}} inches; height {{fraction|5|5|8}} inches. Value £16,000. ({{Inflation|UK|16000|1907|r=-4|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}).{{Inflation-fn|UK|df=y}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/photo-gallery/dmp2/ |title=DMP – poster 2 |year=2007 |orig-date=Original date 8 July 1907 |publisher=Dublin Metropolitan Police |access-date=15 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131019194512/http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%e2%80%9ccrown-jewels%e2%80%9d-2007/photo-gallery/dmp2/ |archive-date=19 October 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

When not being worn or cleaned, the insignia of the Grand Master and those of deceased knights were in the custody of the [[Ulster King of Arms]], the senior Irish [[officer of arms|herald]], and kept in a [[bank vault]].<ref name="dublincastle">{{cite web|url=http://www.dublincastle.ie/HistoryEducation/History/Chapter12TheIllustriousOrderofStPatrick/|title=Chapter 12: The Illustrious Order of St. Patrick|work=History of Dublin Castle|publisher=[[Office of Public Works]]|access-date=14 June 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130511112016/http://www.dublincastle.ie/HistoryEducation/History/Chapter12TheIllustriousOrderofStPatrick/|archive-date=11 May 2013}}</ref> The description "Crown Jewels" was officially applied to the star and badge regalia in a 1905 revision of the order's statutes. The label "Irish Crown Jewels" was publicised by newspapers after their theft.<ref name="Galloway1983">{{cite book |last=Galloway |first=Peter |title=The Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick: 1783 – 1983 |year=1983 |publisher=Phillimore |isbn=9780850335088}}</ref> |

|||

Vicars refused to resign his position as Officer of Arms, and similarly refused to appear at a Viceregal Commission into the theft (the Commission did not possess powers to [[subpoena]] [[witness]]es) held from [[10 January]] [[1908]]. Vicars argued for a public royal inquiry in lieu of the commission, and publicly accused his second in command, [[Francis Shackleton]], of the theft, who was suspected of being blackmailed on account of his [[homosexuality]], homosexual behaviour being a criminal offence at the time.<sup>1</sup> Shackleton was exonerated in the commission's report, and Vicars was found to have "not exercise[d] due vigilance or proper care as the custodian of the regalia'. Vicars met a sad end in disgrace: on [[14 April]] [[1921]] he was shot dead by [[Irish Republican Army|IRA]] militia. The commission's report has been the subject of critical review in recent times (''see external link, below'') and there has been recent calls in the [[Republic of Ireland]] for a centennial enquiry into the [[crime]]. |

|||

==Theft== |

|||

It is believed that the Irish Crown Jewels have never been recovered. It has been rumoured that in [[1927]] the Irish Crown Jewels were offered for sale to the [[Irish Free State]] for £5000 and that they were bought back on then prime minister [[W.T. Cosgrave]]'s orders, with the instructions that the fact that the Irish state owned them was not to be revealed, for fear of criticism from republicans and because of the tight budgetary situation in the [[Irish Free State]]. However an extensive search in the [[Irish National Archives]] has failed to find any evidence that they were bought or if so, what happened to them subsequently. (The Irish state until the [[1940s]] ''did'' have some of the [[Russian Crown Jewels]] which were used as collateral for a loan given to the Russian Republic by the [[Irish Republic]] in or around 1920. It is possible the rumour about the state possessing the Irish Crown Jewels grew because it was known that ''some'' crown jewels were stored in Government Buildings in Dublin, people naturally presuming that they must be the ''Irish'' crown jewels.)<sup>2</sup> |

|||

[[File:Arthur Vicars.jpg|thumb|right|Sir Arthur Vicars]] |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1903, the Office of Arms, the Ulster King of Arms's office within the [[Dublin Castle]] complex, was transferred from the Bermingham Tower to the Bedford or Clock Tower. The jewels were transferred to a new [[safe]], which was to be placed in the newly constructed [[strongroom]]. The new safe was too large for the doorway to the strongroom, and [[Sir Arthur Vicars]], the Ulster King of Arms, instead had it placed in his library.<ref name="AO"/> Seven latch keys to the door of the Office of Arms were held by Vicars and his staff, and two keys to the safe containing the regalia were both in the custody of Vicars. Vicars was known to get drunk on overnight duty and he once awoke to find the jewels around his neck. It is not known whether this was a prank or practice for the actual theft. |

||

The regalia were last worn by the Lord Lieutenant, the [[John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair|Earl of Aberdeen]], on 15 March 1907, at a function to mark [[St Patrick's Day]]. They were last known to be in the safe on 11 June, when Vicars showed them to a visitor to his office. The jewels were discovered to be missing on 6 July 1907, four days before the start of a visit by King [[Edward VII]] and [[Alexandra of Denmark|Queen Alexandra]] to the [[Irish International Exhibition]]; [[Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown|Lord Castletown]] was set to be invested into the order during the visit. The theft is reported to have angered the king, but the visit went ahead.<ref>Legge 1913, p.55</ref> However, the investiture ceremony was cancelled.<ref name="dublincastle" /> Some family jewels inherited by Vicars and valued at £1,500 ({{Inflation|UK|1500|1907|r=-4|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}){{Inflation-fn|UK|df=y}} were also stolen,<ref>{{cite news |author=<!--Staff writer(s)/no by-line.--> |title=The mystery of the missing Crown Jewels |url=https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/the-mystery-of-the-missing-crown-jewels-1.1055099 |newspaper=The Irish Times |date=26 March 2002|access-date=2 March 2021}}</ref> along with the [[Collar (Order of Knighthood)|collar]]s of five members of the order: four living (the [[James Edward William Theobald Butler, 3rd Marquess of Ormonde|Marquess of Ormonde]] and the Earls of [[William Ulick Tristram St Lawrence, 4th Earl of Howth|Howth]], [[Lowry Cole, 4th Earl of Enniskillen|Enniskillen]], and [[Dermot Bourke, 7th Earl of Mayo|Mayo]]) and one deceased (the [[Richard Boyle, 9th Earl of Cork|Earl of Cork]]).<ref name="csorp18119"/> These were valued at £1,050 ({{Inflation|UK|1050|1907|r=-4|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}){{Inflation-fn|UK|df=y}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/photo-gallery/dmp3/|title=DMP – poster 3|year=2007|orig-date=Original date 8 July 1907 |publisher=National Archives of Ireland|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131019201511/http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%e2%80%9ccrown-jewels%e2%80%9d-2007/photo-gallery/dmp3/|archive-date=19 October 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

The Irish Executive Council under [[W.T. Cosgrave]] chose not to keep appointing people to the Order when the [[Irish Free State]] left the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|United Kingdom]] in [[1922]]. Since then, only two people have been appointed to the Order. Both were members of the Royal Family. The then [[Edward VIII of the United Kingdom|Prince of Wales]] (the future King Edward VIII and later Duke of Windsor) was appointed with the agreement of W.T. Cosgrave in [[1928]] while his younger brother, [[Henry, Duke of Gloucester]] was appointed with [[Eamon de Valera]]'s agreement in [[1934]]. The Duke of Gloucester at his death in [[1974]] was the last surviving member of the Order. It has however never actually been abolished and its resurrection has been discussed in Irish government circles on a number of occasions. |

|||

=== |

===Investigation=== |

||

[[File: Irish Crown Jewels.jpg|thumb|right|Dublin Police notice of theft of crown jewels.]] |

|||

A police investigation was conducted by the [[Dublin Metropolitan Police]].<ref name="csorp18119">{{cite report|url=http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/photo-gallery/8-a/|title=Superintendent John Lowe's report – page 1|id=CSORP/1913/18119 – page 1|publisher=National Archives of Ireland|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131019202215/http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%e2%80%9ccrown-jewels%e2%80%9d-2007/photo-gallery/8-a/|archive-date=19 October 2013|url-status=dead}} With links to subsequent pages.</ref> Posters issued by the force depicted and described the missing jewels. Detective Chief Inspector John Kane of [[Scotland Yard]] arrived on 12 July to assist.<ref name="nationalarchives"/> His report, never released, is said to have named the culprit and to have been suppressed by the [[Royal Irish Constabulary]].<ref name="nationalarchives"/> Vicars refused to resign his position, and similarly refused to appear at a Viceregal Commission under Judge [[James Johnston Shaw]] into the theft held from 10 January 1908. Vicars argued for a public [[Royal Commission]] instead, which would have had power to [[subpoena]] [[witness]]es.<ref name="AO"/> He publicly accused his second in command, Francis (Frank) Shackleton, Dublin Herald of Arms, of the theft. Kane explicitly denied to the Commission that Shackleton, brother of the explorer [[Ernest Shackleton]], was involved. Shackleton was exonerated in the commission's report, and Vicars was found to have "not exercise[d] due vigilance or proper care as the custodian of the regalia." Vicars was compelled to resign, as were all the staff in his personal employ. |

|||

===Rumours and theories=== |

|||

<sup>1</sup> Rumours of a homosexual ring in [[Dublin Castle]] were linked to claims about the theft. It was variously rumoured that Shackleton and/or Vicars were being blackmailed on account of their orientation, they or others in the Castle facilitating the theft to pay off the blackmailers or to "expose" Vicars' rumoured sex-life through an inquiry into the theft. The claim of gay rings in Dublin Castle was nothing new. One nationalist MP during the [[Lord Lieutenant|lord lieutenancy]] of the 5th Earl Spencer in the [[1880s]] famously nicknamed the Lord Lieutenant's Dublin Castle administration ''Sodom and Begorrah''. |

|||

In 1908, the Irish journalist [[Bulmer Hobson]] published an account of the theft in a radical American newspaper, ''The Gaelic American'', using information he had received from Vicars' half-brother [[Pierce Charles de Lacy O'Mahony|Pierce O'Mahony]]. It stated that the culprits were Shackleton and a military officer, [[Richard William Howard Gorges|Richard Gorges]]. The two men allegedly obtained access to the safe by plying Vicars with whiskey until he fell unconscious, at which point they removed the key from his pocket. Once the jewels had been extricated, Shackleton transported them to [[Amsterdam]], where he sold them for £20,000. Hobson claimed that the men escaped prosecution due to Shackleton threatening to expose the "discreditable doings" of various high-ranking personages with whom he was acquainted. Hobson repeated the allegations in a formal statement to officials in 1955, and in his autobiography.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Ireland Yesterday and Tomorrow|last = Hobson|first = Bulmer|publisher = Tralee|year = 1968 |pages=85–88}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921/reels/bmh/BMH.WS1089.pdf|title=W.S. 1089: Statement of Mr. Bulmer Hobson|date=1955|publisher=Irish Military Archives|access-date=10 December 2023}}</ref> |

|||

Officials were aware of the homosexuality of Shackleton, Gorges and Vicars<ref>Cafferky, John; Hannafin, Kevin, ''Scandal & Betrayal: Shackleton and the Irish Crown Jewels'', pp72, 225, passim.</ref> and the claim that the investigation was compromised to avoid a greater scandal, such as the [[John Saul (prostitute)|Dublin Castle homosexual scandals of 1884]], was also made by Vicars, including in his will. The Lord Lieutenant's son, Lord Haddo, had been a participant in the parties at the Castle, and King Edward VII's allegedly bisexual brother-in-law the [[John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll|Duke of Argyll]] was known to Frank Shackleton, through a friendship with the prominent social figure [[Lord Ronald Gower]].<ref>Jordaan, Peter, ''A Secret Between Gentlemen (vol 1): Lord Battersea's Hidden Scandal And The Lives It Changed Forever'', Alchemie Books 2023, p663</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title = Princes Under The Volcano|last = Trevelyan|first = Raleigh|publisher = William Morrow & Company|year = 1978|pages = 337–8}}</ref> |

|||

<sup>2</sup> The new Russian Republic, which was seriously low on funds, apparently sought the loan from the [[Unilateral Declaration of Independence|UDI]] [[Irish Republic]], whose Finance Minister, [[Michael Collins (Irish leader)|Michael Collins]], had become internationally famous for his fundraising for the unofficial Irish state. The Jewels were placed in a safe in Government Buildings and promptly forgotten about, though the existence of some crown jewels somewhere was rumoured. They were rediscovered in the 1940s by accident and sent to [[Moscow]]. It is not known if [[Josef Stalin]] repaid the loan. |

|||

Of the persons alleged to be involved in the theft: |

|||

==Additional Reading== |

|||

* Sir Arthur Vicars was killed by the [[Irish Republican Army (1919–1922)|IRA]] in [[County Kerry]] in April 1921. |

|||

* Frank Shackleton defrauded [[Lord Ronald Gower]] of his fortune between 1910 and 1913. Shackleton was eventually prosecuted and imprisoned, but only for defrauding a spinster friend of Gower's, even though it was for a far smaller sum. It has been surmised this legal oddity was due to the British Government's desire not to provoke Shackleton unduly, or probe Gower, over fear prominent names might be voiced.<ref>Jordaan, Peter, ''A Secret Between Gentlemen: Suspects, Strays and Guests'', Alchemie Books 2023, p92.</ref> Upon release from prison, Shackleton changed his name to Mellor and became an antiques dealer in [[Chichester]], England, until his death on 24 June 1941, aged 64. |

|||

* Richard Gorges shot and killed a policeman in 1915, and served 10 years of a 12-year sentence. In May 1941, Gorges was arrested and again sent to [[gaol]] for obtaining clothes from [[Simpsons of Piccadilly]] with a worthless cheque. In January 1944 he was killed after being run over by a train in the [[London Underground]]. |

|||

Only a short time after the theft, accusations began to be made, most especially by overseas press, that proper investigation of the theft was being suppressed by the British Government to protect prominent names. This led to such claims regularly being made in Parliament by Irish MPs for several years.<ref>Jordaan, Peter, ''A Secret Between Gentlemen: Lord Battersea's Hidden Scandal And The Lives It Changed Forever, Alchemie Books, 2023, pp 636–672.</ref> |

|||

Tim Coates (ed.), ''The Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels'' (Tim Coates, 2003) ISBN 1843810077 |

|||

There was a theory that the jewels were stolen by political activists who were in the [[Irish Republican Brotherhood]].<ref name="Riordan2001" /> In the [[House of Commons of the United Kingdom|House of Commons]] in August 1907, [[Pat O'Brien (Irish politician)|Pat O'Brien]], [[Members of Parliament|MP]], blamed "loyal and patriotic [[Unionism in Ireland|Unionist]] criminals".<ref>[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1907/aug/13/the-theft-of-the-irish-crown-jewels HC Deb 13 August 1907 vol 180 cc1065-6]</ref> [[George Gordon, 2nd Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair|Lord Haddo]], the son of the Lord Lieutenant, was alleged by some newspapers to have been involved in the theft;<ref>Legge 1913, pp. xv, 62–63</ref> [[Augustine Birrell]], the [[Chief Secretary for Ireland]], stated in the Commons that Haddo had been in [[Great Britain]] throughout the time period within which the theft took place.<ref>[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1908/apr/01/the-theft-of-the-dublin-crown-jewels HC Deb 01 April 1908 vol 187 cc509-10]</ref> In 1912 and 1913, [[Laurence Ginnell]] suggested that the police investigation had established the identity of the thief, that his report had been suppressed to avoid scandal,<ref name="hc1913v47c1189">[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1913/jan/28/crown-jewels-ireland HC Deb 28 January 1913 vol 47 cc1189-90]</ref> and that the jewels were "at present within the reach of the Irish Government awaiting the invention of some plausible method of restoring them without getting entangled in the Criminal Law".<ref>[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1913/jan/23/crown-jewels-ireland HC Deb 23 January 1913 vol 47 cc589-90]</ref> In an [[adjournment debate]] in 1912 he alleged:<ref name="hc1912v44c2751">[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1912/dec/06/irish-crown-jewels HC Deb 06 December 1912 vol 44 cc2751-2]</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{blockquote|The proposition I ask to be allowed to make is this: The police charged with collecting evidence in connection with the disappearance of the Crown Jewels from Dublin Castle in 1907 collected evidence inseparable from it of criminal debauchery and [[sodomy]] being committed in the castle by officials, Army officers, and a couple of nondescripts of such position that their conviction and exposure would have led to an upheaval from which the Chief Secretary shrank. In order to prevent that he suspended the operation of the Criminal Law, and appointed a whitewashing commission with the result for which it was appointed.}} |

|||

*[http://www.dublincastle.ie/history12.html Dublin Castle's commentary on the theft] |

|||

His speech was curtailed when a [[quorum]] of forty MPs was not present in the chamber.<ref name="hc1912v44c2751" /> He elaborated the following week on the alleged depravity of "two of the characters", namely army captain [[Richard William Howard Gorges|Richard Gorges]] ("a reckless bully, a robber, a murderer, a bugger, and a sod") and Shackleton ("One of [Gorges'] chums in the Castle, and a participant in the debauchery").<ref name="hc19121220"/> Birrell denied any cover-up and urged Ginnell to give to the police any evidence he had relating to the theft or any sexual crime.<ref name="hc19121220">[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1912/dec/20/crown-jewels-dublin HC Deb 20 December 1912 vol 45 cc1955-62]</ref> [[Walter Vavasour Faber]] also asked about a cover-up;<ref>[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1913/feb/13/crown-jewels-dublin HC Deb 13 February 1913 vol 48 cc1159-61]</ref> Edward Legge supported this theory.<ref>Legge 1913, pp. 64–65</ref> |

|||

On 23 November 1912, the ''London Mail'' alleged that Vicars had allowed a woman reported to be his mistress to obtain a copy to the key to the safe and that she had fled to Paris with the jewels. In July 1913, Vicars sued the paper for [[libel]]; it admitted that the story was completely baseless and that the woman in question did not exist; Vicars was awarded [[damages]] of £5,000.<ref>{{cite news|title=The Irish Crown Jewels|url=http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19130829.2.25|access-date=29 August 2015|volume=XLVII|issue=20|publisher=Marlborough Express|date=29 August 1913}}</ref> Vicars left nothing in his will to his half-brother Pierce O'Mahony, on the grounds that O'Mahony had repudiated a promise to recompense Vicars for the loss of income caused by his resignation.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nationalarchives.ie/topics/crown_jewels/VicarsWill/1/will.html|title=Will of Sir Arthur Vicars|publisher=National Archives of Ireland, Principal Registry|page=4|date=20 March 1922}}</ref> |

|||

After Frank Shackleton was imprisoned in 1914 for passing a [[cheque]] stolen from a spinster,<ref name="dublincastle" /><ref name="paperspast_AS19130308">{{cite news|url=http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=AS19130308.2.108.5&dliv=&e=--1913---1914--10--1-byDA---0surrey+shipping+arrivals--|title=The Case of Francis Shackleton|date=8 March 1913|work=Auckland Star|page=13|access-date=14 June 2013}}</ref> [[Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton|Earl Winterton]] asked for the [[judicial inquiry]] demanded by Vicars.<ref>[https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1914/feb/19/crown-jewels-dublin HC Deb 19 February 1914 vol 58 cc1113-4]</ref> |

|||

A 1927 memo of the [[Executive Council of the Irish Free State]], released in the 1970s, stated that [[W. T. Cosgrave]] "understands that the Castle jewels are for sale and that they could be got for £2,000 or £3,000."<ref name="Riordan2001" /> However, it has been suggested that this is a misunderstanding, the memorandum having resulted from a communication to Cosgrave from a Dublin jeweller, James Weldon, who had been theoretically offered the jewels by a man fitting the description of Frank Shackleton, but in 1908.<ref name="Miles Dungan 2002, p61">Miles Dungan, 'A Gem Of A Robbery', ''Sunday Tribune'', 14 April 2002, p61</ref> |

|||

[[File:Captain Gorges.JPG|thumb|Captain Richard Howard Gorges at his trial 1915]] |

|||

In 1965, ''Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown Jewels'' was published. While not ascribing definitive responsibility for the theft,<ref name="Miles Dungan 2002, p61"/> it was the most detailed account to that date. In 2002, another published account, ''Scandal & Betrayal: Shackleton And The Irish Crown Jewels'' suggested the theft was a Unionist plot to embarrass [[Liberal Government 1905–1915|the Liberal government]]. A reviewer called it "speculation and allegation dressed up as history".<ref name="Miles Dungan 2002, p61"/> A 2003 study, ''The Stealing Of The Irish Crown Jewels'', stated that while Shackleton and Gorges may have been shielded from prosecution due to fears they would expose homosexuality in prominent figures, this was only speculation, and the police may simply not have had enough evidence against them.<ref>Dungan, Myes, ''The Stealing Of The Irish Crown Jewels - an unsolved crime,'', Town House, Dublin 2003, p342</ref> In 2023, ''A Secret Between Gentlemen'' further detailed the British Government's suppression of the case, and its hesitancy in prosecuting Shackleton in 1913 over his defrauding of Gower's fortune.<ref>Jordaan, Peter, ''A Secret Between Gentlemen'', Alchemie Books, 2023, Vol 1, pp636-672; Vol 2, pp84-92</ref> It served to strengthen Bulmer Hobson's allegation over the reason for the Government's behaviour in 1908. |

|||

Folklore within the [[Genealogical Office]] of the [[Republic of Ireland]], the successor to the Office of Arms, was that the jewels were never removed from the Clock Tower, but were merely hidden. In 1983, when the Genealogical Office vacated its structurally unsound premises inside the Clock Tower, Donal Begley, the then-[[Chief Herald of Ireland]] supervised the removal of walls and floorboards, in case the jewels were found, but they were not.<ref>Hood 2002 pp.232–233</ref> |

|||

===Fictional accounts=== |

|||

A 1967 book suggests that the 1908 [[Sherlock Holmes]] story "[[The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans]]" was inspired by the theft; author [[Sir Arthur Conan Doyle]] was a friend of Vicars, and the fictional Valentine Walters, who steals the Plans but is caught by Holmes, has similarities with Francis Shackleton.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bamford |first1=Francis |last2=Bankes |first2=Viola |title=Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown Jewels |url=https://archive.org/details/viciouscirclecas00bamf |url-access=registration |year=1967 |publisher=Horizon Press}}</ref> |

|||

''Jewels'', a Bob Perrin novel based on the theft, was published in 1977.<ref name="Perrin1977">{{cite book|last=Perrin|first=Robert|title=Jewels|year=1977|publisher=Pan Books|isbn=9780330255875}}</ref> |

|||

''The Case of the Crown Jewels'' by [[Donald Serrell Thomas]], a Sherlock Holmes story based on the theft, was published in 1997. |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Hood |first1=Susan |title=Royal Roots, Republican Inheritance: The Survival of the Office of Arms |date=2002 |publisher=Woodfield Press in association with [[National Library of Ireland]] |location=Dublin |isbn=9780953429332 |language=en}} |

|||

* {{cite book |title=Statutes and Ordinances of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick |date=1852 |publisher=George & John Grierson for [[Her Majesty's Stationery Office]] |location=Dublin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9rFXAAAAcAAJ |access-date=1 November 2019 |language=en}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Legge |first=Edward |title=More about King Edward |url=https://archive.org/details/moreaboutkingedw00leggrich |year=1913 |publisher=Small, Maynard |location=Boston}} |

|||

* {{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/op1255337-1001 |title=Report |series=[[Command paper]]s |volume=Cd.3906 |access-date=31 October 2019 |via=[[Internet Archive]] |date=1908 |author=Viceregal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick |publisher=HMSO }} |

|||

* {{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/op1255338-1001 |title=Appendix |series=[[Command paper]]s |volume=Cd.3936 |access-date=31 October 2019 |via=[[Internet Archive]] |date=1908 |author=Viceregal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick |publisher=HMSO }} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Bankes |first1=Viola |last2=Bamford |first2=Francis |title=Vicious Circle: The Case Of The Missing Irish Crown Jewels |publisher=Max Parrish and Co. |place=London |date=1965 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Cafferky |first1=John |last2=Hannafin |first2=Kevin |title=Scandal & Betrayal: Shackleton And The Irish Crown Jewels |publisher=The Collins Press |place=Cork |date=2002 |isbn=9781903464250}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Dungan |first=Myes |title=The Stealing Of The Irish Crown Jewels - an unsolved crime |publisher=Town House |place=Dublin |date=2003 | isbn=9781860591822}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Jordaan |first=Peter |title=A Secret Between Gentlemen (vol 1): Lord Battersea's Hidden Scandal And The Lives It Changed Forever |publisher=Alchemie Books |place=Sydney |date=2023 |isbn=9780645617870}} {{cite book |title=A Secret Between Gentlemen (vol 2): Suspects, Strays and Guests |publisher=Alchemie Books |place=Sydney |date=2023 |isbn=9780645852745}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Galloway |first=Peter |title=The Most Illustrious Order: The Order of Saint Patrick and its Knights |publisher=Unicorn Press |place=London |date=1999 |isbn=0-906290-23-6}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{commons category|Irish Crown Jewels}} |

|||

* {{cite web |url=http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/jewels.htm |title=A Centenary Report on the Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907 |work=Irish Historical Mysteries |first=Sean J |last=Murphy |date=29 April 2008 |publisher=Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies |location=Bray, Co. Wicklow, Ireland |access-date=14 June 2013 }} |

|||

* {{cite web |url=https://www.nationalarchives.ie/topics/crown_jewels/ |title=The Theft of the Irish 'Crown Jewels' |work=Online exhibitions |date=2007 |access-date=1 November 2019 |publisher=[[National Archives of Ireland]] |location=Dublin}} |

|||

{{History of Dublin}} |

|||

*[http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/ Analysis of the theft and key suspects.] |

|||

{{Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom}} |

|||

{{Crown jewels by country}} |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:1783 in Ireland]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:1907 in Ireland]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Monarchy of the United Kingdom]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Monarchy of Ireland]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:National symbols of Ireland]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Unsolved crimes in Ireland]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Individual thefts]] |

||

[[Category:Robberies in the United Kingdom]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 21:08, 2 June 2024

The Jewels of the Order of St Patrick, commonly called the Irish Crown Jewels, were the heavily jewelled badge and star created in 1831 for the Grand Master of the Order of St Patrick, an order of knighthood established in 1783 by George III to be an Irish equivalent of the English Order of the Garter and the Scottish Order of the Thistle. The office of Grand Master was held by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

The jewels were stolen from Dublin Castle in 1907, along with the collars of five knights of the order. The theft has never been solved, and the items have never been recovered.[1]

History

[edit]

The original regalia of the Grand Master were only slightly more opulent than the insignia of an ordinary member of the order; the king's 1783 ordinance said they were to be "of the same materials and fashion as those of Our Knights, save only those alterations which befit Our dignity".[2] The regalia were replaced in 1831 by new ones presented by William IV as part of a revision of the order's structure. They were delivered from London to Dublin on 15 March by the Earl of Erroll in a mahogany box together with a document titled "A Description of the Jewels of the Order of St. Patrick, made by command of His Majesty King William the Fourth, for the use of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and which are Crown Jewels."[3] They contained 394 precious stones taken from the English Crown Jewels of Queen Charlotte and the Order of the Bath star of her husband George III.[4] The jewels were assembled by Rundell & Bridge. On the badge, of St Patrick's blue enamel, the green shamrock was of emeralds and the red saltire of rubies; the motto of the order was in pink diamonds and the encrustation was of Brazilian diamonds of the first water.[4][5] Notices issued after the theft described the jewels thus:

A Diamond Star of the Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick composed of brilliants (Brazilian stones) of the purest water, 4+5⁄8 by 4+1⁄4 inches, consisting of eight points, four greater and four lesser, issuing from a centre enclosing a cross of rubies and a trefoil of emeralds surrounding a sky blue enamel circle with words, "Quis Separabit MDCCLXXXIII." in rose diamonds engraved on back. Value about £14,000. (equivalent to £1,870,000 in 2023).[6][7]

A Diamond Badge of the Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick set in silver containing a trefoil in emeralds on a ruby cross surrounded by a sky blue enamelled circle with "Quis Separabit MDCCLXXXIII." in rose diamonds surrounded by a wreath of trefoils in emeralds, the whole enclosed by a circle of large single Brazilian stones of the finest water, surmounted by a crowned harp in diamonds and loop, also in Brazilian stones. Total size of oval 3 by 2+3⁄8 inches; height 5+5⁄8 inches. Value £16,000. (equivalent to £2,140,000 in 2023).[6][8]

When not being worn or cleaned, the insignia of the Grand Master and those of deceased knights were in the custody of the Ulster King of Arms, the senior Irish herald, and kept in a bank vault.[9] The description "Crown Jewels" was officially applied to the star and badge regalia in a 1905 revision of the order's statutes. The label "Irish Crown Jewels" was publicised by newspapers after their theft.[10]

Theft

[edit]

In 1903, the Office of Arms, the Ulster King of Arms's office within the Dublin Castle complex, was transferred from the Bermingham Tower to the Bedford or Clock Tower. The jewels were transferred to a new safe, which was to be placed in the newly constructed strongroom. The new safe was too large for the doorway to the strongroom, and Sir Arthur Vicars, the Ulster King of Arms, instead had it placed in his library.[1] Seven latch keys to the door of the Office of Arms were held by Vicars and his staff, and two keys to the safe containing the regalia were both in the custody of Vicars. Vicars was known to get drunk on overnight duty and he once awoke to find the jewels around his neck. It is not known whether this was a prank or practice for the actual theft.

The regalia were last worn by the Lord Lieutenant, the Earl of Aberdeen, on 15 March 1907, at a function to mark St Patrick's Day. They were last known to be in the safe on 11 June, when Vicars showed them to a visitor to his office. The jewels were discovered to be missing on 6 July 1907, four days before the start of a visit by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra to the Irish International Exhibition; Lord Castletown was set to be invested into the order during the visit. The theft is reported to have angered the king, but the visit went ahead.[11] However, the investiture ceremony was cancelled.[9] Some family jewels inherited by Vicars and valued at £1,500 (equivalent to £200,000 in 2023)[6] were also stolen,[12] along with the collars of five members of the order: four living (the Marquess of Ormonde and the Earls of Howth, Enniskillen, and Mayo) and one deceased (the Earl of Cork).[13] These were valued at £1,050 (equivalent to £140,000 in 2023)[6].[14]

Investigation

[edit]

A police investigation was conducted by the Dublin Metropolitan Police.[13] Posters issued by the force depicted and described the missing jewels. Detective Chief Inspector John Kane of Scotland Yard arrived on 12 July to assist.[5] His report, never released, is said to have named the culprit and to have been suppressed by the Royal Irish Constabulary.[5] Vicars refused to resign his position, and similarly refused to appear at a Viceregal Commission under Judge James Johnston Shaw into the theft held from 10 January 1908. Vicars argued for a public Royal Commission instead, which would have had power to subpoena witnesses.[1] He publicly accused his second in command, Francis (Frank) Shackleton, Dublin Herald of Arms, of the theft. Kane explicitly denied to the Commission that Shackleton, brother of the explorer Ernest Shackleton, was involved. Shackleton was exonerated in the commission's report, and Vicars was found to have "not exercise[d] due vigilance or proper care as the custodian of the regalia." Vicars was compelled to resign, as were all the staff in his personal employ.

Rumours and theories

[edit]In 1908, the Irish journalist Bulmer Hobson published an account of the theft in a radical American newspaper, The Gaelic American, using information he had received from Vicars' half-brother Pierce O'Mahony. It stated that the culprits were Shackleton and a military officer, Richard Gorges. The two men allegedly obtained access to the safe by plying Vicars with whiskey until he fell unconscious, at which point they removed the key from his pocket. Once the jewels had been extricated, Shackleton transported them to Amsterdam, where he sold them for £20,000. Hobson claimed that the men escaped prosecution due to Shackleton threatening to expose the "discreditable doings" of various high-ranking personages with whom he was acquainted. Hobson repeated the allegations in a formal statement to officials in 1955, and in his autobiography.[15][16]

Officials were aware of the homosexuality of Shackleton, Gorges and Vicars[17] and the claim that the investigation was compromised to avoid a greater scandal, such as the Dublin Castle homosexual scandals of 1884, was also made by Vicars, including in his will. The Lord Lieutenant's son, Lord Haddo, had been a participant in the parties at the Castle, and King Edward VII's allegedly bisexual brother-in-law the Duke of Argyll was known to Frank Shackleton, through a friendship with the prominent social figure Lord Ronald Gower.[18][19]

Of the persons alleged to be involved in the theft:

- Sir Arthur Vicars was killed by the IRA in County Kerry in April 1921.

- Frank Shackleton defrauded Lord Ronald Gower of his fortune between 1910 and 1913. Shackleton was eventually prosecuted and imprisoned, but only for defrauding a spinster friend of Gower's, even though it was for a far smaller sum. It has been surmised this legal oddity was due to the British Government's desire not to provoke Shackleton unduly, or probe Gower, over fear prominent names might be voiced.[20] Upon release from prison, Shackleton changed his name to Mellor and became an antiques dealer in Chichester, England, until his death on 24 June 1941, aged 64.

- Richard Gorges shot and killed a policeman in 1915, and served 10 years of a 12-year sentence. In May 1941, Gorges was arrested and again sent to gaol for obtaining clothes from Simpsons of Piccadilly with a worthless cheque. In January 1944 he was killed after being run over by a train in the London Underground.

Only a short time after the theft, accusations began to be made, most especially by overseas press, that proper investigation of the theft was being suppressed by the British Government to protect prominent names. This led to such claims regularly being made in Parliament by Irish MPs for several years.[21]

There was a theory that the jewels were stolen by political activists who were in the Irish Republican Brotherhood.[4] In the House of Commons in August 1907, Pat O'Brien, MP, blamed "loyal and patriotic Unionist criminals".[22] Lord Haddo, the son of the Lord Lieutenant, was alleged by some newspapers to have been involved in the theft;[23] Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, stated in the Commons that Haddo had been in Great Britain throughout the time period within which the theft took place.[24] In 1912 and 1913, Laurence Ginnell suggested that the police investigation had established the identity of the thief, that his report had been suppressed to avoid scandal,[25] and that the jewels were "at present within the reach of the Irish Government awaiting the invention of some plausible method of restoring them without getting entangled in the Criminal Law".[26] In an adjournment debate in 1912 he alleged:[27]

The proposition I ask to be allowed to make is this: The police charged with collecting evidence in connection with the disappearance of the Crown Jewels from Dublin Castle in 1907 collected evidence inseparable from it of criminal debauchery and sodomy being committed in the castle by officials, Army officers, and a couple of nondescripts of such position that their conviction and exposure would have led to an upheaval from which the Chief Secretary shrank. In order to prevent that he suspended the operation of the Criminal Law, and appointed a whitewashing commission with the result for which it was appointed.

His speech was curtailed when a quorum of forty MPs was not present in the chamber.[27] He elaborated the following week on the alleged depravity of "two of the characters", namely army captain Richard Gorges ("a reckless bully, a robber, a murderer, a bugger, and a sod") and Shackleton ("One of [Gorges'] chums in the Castle, and a participant in the debauchery").[28] Birrell denied any cover-up and urged Ginnell to give to the police any evidence he had relating to the theft or any sexual crime.[28] Walter Vavasour Faber also asked about a cover-up;[29] Edward Legge supported this theory.[30]

On 23 November 1912, the London Mail alleged that Vicars had allowed a woman reported to be his mistress to obtain a copy to the key to the safe and that she had fled to Paris with the jewels. In July 1913, Vicars sued the paper for libel; it admitted that the story was completely baseless and that the woman in question did not exist; Vicars was awarded damages of £5,000.[31] Vicars left nothing in his will to his half-brother Pierce O'Mahony, on the grounds that O'Mahony had repudiated a promise to recompense Vicars for the loss of income caused by his resignation.[32]

After Frank Shackleton was imprisoned in 1914 for passing a cheque stolen from a spinster,[9][33] Earl Winterton asked for the judicial inquiry demanded by Vicars.[34]

A 1927 memo of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, released in the 1970s, stated that W. T. Cosgrave "understands that the Castle jewels are for sale and that they could be got for £2,000 or £3,000."[4] However, it has been suggested that this is a misunderstanding, the memorandum having resulted from a communication to Cosgrave from a Dublin jeweller, James Weldon, who had been theoretically offered the jewels by a man fitting the description of Frank Shackleton, but in 1908.[35]

In 1965, Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown Jewels was published. While not ascribing definitive responsibility for the theft,[35] it was the most detailed account to that date. In 2002, another published account, Scandal & Betrayal: Shackleton And The Irish Crown Jewels suggested the theft was a Unionist plot to embarrass the Liberal government. A reviewer called it "speculation and allegation dressed up as history".[35] A 2003 study, The Stealing Of The Irish Crown Jewels, stated that while Shackleton and Gorges may have been shielded from prosecution due to fears they would expose homosexuality in prominent figures, this was only speculation, and the police may simply not have had enough evidence against them.[36] In 2023, A Secret Between Gentlemen further detailed the British Government's suppression of the case, and its hesitancy in prosecuting Shackleton in 1913 over his defrauding of Gower's fortune.[37] It served to strengthen Bulmer Hobson's allegation over the reason for the Government's behaviour in 1908.

Folklore within the Genealogical Office of the Republic of Ireland, the successor to the Office of Arms, was that the jewels were never removed from the Clock Tower, but were merely hidden. In 1983, when the Genealogical Office vacated its structurally unsound premises inside the Clock Tower, Donal Begley, the then-Chief Herald of Ireland supervised the removal of walls and floorboards, in case the jewels were found, but they were not.[38]

Fictional accounts

[edit]A 1967 book suggests that the 1908 Sherlock Holmes story "The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans" was inspired by the theft; author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a friend of Vicars, and the fictional Valentine Walters, who steals the Plans but is caught by Holmes, has similarities with Francis Shackleton.[39]

Jewels, a Bob Perrin novel based on the theft, was published in 1977.[40]

The Case of the Crown Jewels by Donald Serrell Thomas, a Sherlock Holmes story based on the theft, was published in 1997.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Nosowitz, Dan (4 November 2021). "The Greatest Unsolved Heist in Irish History". Atlas Obscura – Stories. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Statutes and Ordinances 1852, pp.46–47

- ^ Statutes and Ordinances 1852, pp.104–105

- ^ a b c d O'Riordan, Tomás (Winter 2001). "The Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels, 1907". History Ireland. 9 (4).

- ^ a b c "The Theft of the Irish 'Crown Jewels'". Online exhibitions. Dublin: National Archives of Ireland. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "DMP – poster 1". Dublin Metropolitan Police. 2007 [Original date 8 July 1907]. Archived from the original on 6 February 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "DMP – poster 2". Dublin Metropolitan Police. 2007 [Original date 8 July 1907]. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "Chapter 12: The Illustrious Order of St. Patrick". History of Dublin Castle. Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Galloway, Peter (1983). The Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick: 1783 – 1983. Phillimore. ISBN 9780850335088.

- ^ Legge 1913, p.55

- ^ "The mystery of the missing Crown Jewels". The Irish Times. 26 March 2002. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b Superintendent John Lowe's report – page 1 (Report). National Archives of Ireland. CSORP/1913/18119 – page 1. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. With links to subsequent pages.

- ^ "DMP – poster 3". National Archives of Ireland. 2007 [Original date 8 July 1907]. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ Hobson, Bulmer (1968). Ireland Yesterday and Tomorrow. Tralee. pp. 85–88.

- ^ "W.S. 1089: Statement of Mr. Bulmer Hobson" (PDF). Irish Military Archives. 1955. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Cafferky, John; Hannafin, Kevin, Scandal & Betrayal: Shackleton and the Irish Crown Jewels, pp72, 225, passim.

- ^ Jordaan, Peter, A Secret Between Gentlemen (vol 1): Lord Battersea's Hidden Scandal And The Lives It Changed Forever, Alchemie Books 2023, p663

- ^ Trevelyan, Raleigh (1978). Princes Under The Volcano. William Morrow & Company. pp. 337–8.

- ^ Jordaan, Peter, A Secret Between Gentlemen: Suspects, Strays and Guests, Alchemie Books 2023, p92.

- ^ Jordaan, Peter, A Secret Between Gentlemen: Lord Battersea's Hidden Scandal And The Lives It Changed Forever, Alchemie Books, 2023, pp 636–672.

- ^ HC Deb 13 August 1907 vol 180 cc1065-6

- ^ Legge 1913, pp. xv, 62–63

- ^ HC Deb 01 April 1908 vol 187 cc509-10

- ^ HC Deb 28 January 1913 vol 47 cc1189-90

- ^ HC Deb 23 January 1913 vol 47 cc589-90

- ^ a b HC Deb 06 December 1912 vol 44 cc2751-2

- ^ a b HC Deb 20 December 1912 vol 45 cc1955-62

- ^ HC Deb 13 February 1913 vol 48 cc1159-61

- ^ Legge 1913, pp. 64–65

- ^ "The Irish Crown Jewels". Vol. XLVII, no. 20. Marlborough Express. 29 August 1913. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Will of Sir Arthur Vicars". National Archives of Ireland, Principal Registry. 20 March 1922. p. 4.

- ^ "The Case of Francis Shackleton". Auckland Star. 8 March 1913. p. 13. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ HC Deb 19 February 1914 vol 58 cc1113-4

- ^ a b c Miles Dungan, 'A Gem Of A Robbery', Sunday Tribune, 14 April 2002, p61

- ^ Dungan, Myes, The Stealing Of The Irish Crown Jewels - an unsolved crime,, Town House, Dublin 2003, p342

- ^ Jordaan, Peter, A Secret Between Gentlemen, Alchemie Books, 2023, Vol 1, pp636-672; Vol 2, pp84-92

- ^ Hood 2002 pp.232–233

- ^ Bamford, Francis; Bankes, Viola (1967). Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown Jewels. Horizon Press.

- ^ Perrin, Robert (1977). Jewels. Pan Books. ISBN 9780330255875.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hood, Susan (2002). Royal Roots, Republican Inheritance: The Survival of the Office of Arms. Dublin: Woodfield Press in association with National Library of Ireland. ISBN 9780953429332.

- Statutes and Ordinances of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick. Dublin: George & John Grierson for Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1852. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Legge, Edward (1913). More about King Edward. Boston: Small, Maynard.

- Viceregal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick (1908). Report. Command papers. Vol. Cd.3906. HMSO. Retrieved 31 October 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Viceregal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick (1908). Appendix. Command papers. Vol. Cd.3936. HMSO. Retrieved 31 October 2019 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

[edit]- Bankes, Viola; Bamford, Francis (1965). Vicious Circle: The Case Of The Missing Irish Crown Jewels. London: Max Parrish and Co.

- Cafferky, John; Hannafin, Kevin (2002). Scandal & Betrayal: Shackleton And The Irish Crown Jewels. Cork: The Collins Press. ISBN 9781903464250.

- Dungan, Myes (2003). The Stealing Of The Irish Crown Jewels - an unsolved crime. Dublin: Town House. ISBN 9781860591822.

- Jordaan, Peter (2023). A Secret Between Gentlemen (vol 1): Lord Battersea's Hidden Scandal And The Lives It Changed Forever. Sydney: Alchemie Books. ISBN 9780645617870. A Secret Between Gentlemen (vol 2): Suspects, Strays and Guests. Sydney: Alchemie Books. 2023. ISBN 9780645852745.

- Galloway, Peter (1999). The Most Illustrious Order: The Order of Saint Patrick and its Knights. London: Unicorn Press. ISBN 0-906290-23-6.

External links

[edit]- Murphy, Sean J (29 April 2008). "A Centenary Report on the Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907". Irish Historical Mysteries. Bray, Co. Wicklow, Ireland: Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "The Theft of the Irish 'Crown Jewels'". Online exhibitions. Dublin: National Archives of Ireland. 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2019.